Pull Focus: Josh Fox

By Matt Gordon and Lauren Donia

Josh Fox is the founder and Artistic Director of International WOW Company a film and theater company in New York. In addition to having written/directed/produced more than twenty plays, Josh directed the narrative feature film MEMORIAL DAY (2008) and most recently the Academy Award nominated documentary feature GASLAND (2010). The film is a personal investigation into the domestic natural gas drilling industry and its devastating impacts on the environment and human health. Josh as been touring the country with his film and on March 17th, 2011 Josh, joined us here at American University as part of the Center for Social Media’s Visiting Filmmakerseries (video of Fox’s talk available here). Before his screening, we had a chance to sit down with Josh to learn more about his approach to filmmaking and creating social change through media.

into the domestic natural gas drilling industry and its devastating impacts on the environment and human health. Josh as been touring the country with his film and on March 17th, 2011 Josh, joined us here at American University as part of the Center for Social Media’s Visiting Filmmakerseries (video of Fox’s talk available here). Before his screening, we had a chance to sit down with Josh to learn more about his approach to filmmaking and creating social change through media.

GASLAND is a social issue film that not only has a strong personal story, but strong aesthetic choices as well. Could you talk about why you made those choices and how you came to them?

JOSH FOX: Well, I don’t come into this as a documentary filmmaker. I’m not a documentary filmmaker. I am now, I wasn’t then. I work in a theater. My life’s work is as the artistic director of an international Avant-garde theater company called International WOW. So I think for me it’s important to have equal emphasis on content and form. Before GASLAND, I had made a film called Memorial Day, which was a first person really guerilla film that had very subjective camera work. When I started GASLAND, I actually had never shot anything in the daytime. So I was trying to find settings that gave me the look that I wanted on the camera that I was using at first, which was the Sony PD170 not the industry standard Sony PD150. I think you always want things to be alive. The thing that I find so often with documentaries is that there is an over emphasis on content and no consideration for the aesthetics. And that’s a problem I think because you get people tuning out. There’s got to be a reason you’re watching the film. A very small percentage of your target audience — or your audience at all — will be invested in the issue to begin with. And if they are, then you kind of don’t need to make the movie. You need to get people interested who are not already involved. One of the ways you do that is by working on it from a story perspective, from a narrative perspective, from making a good movie period, rather than just making a good document of what’s happening.

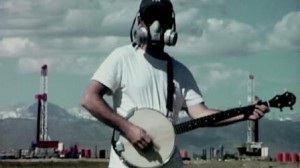

My story being in the film was a decision, and the shooting style is first person, so there are shots that feel like they’re being done by…well, I mean, it is being done by me. A lot of it was shot alone and driving around the American west with a camera in the car and sometimes I would be driving and filming myself. That’s just the way that it was most convenient to do it. So there is a sort of cinéma vérité style, but it’s much deeper than that. Matt Sanchez, the editor and I, found innovative ways of making the footage look the way we wanted it to look through color correction. The first shot, which is on the poster with me playing the banjo was actually processed quite a lot to make it look that way and give it that pastel kind of feel. It was shot, then projected on a wall and then shot again in HD so that you had both the way the projection looked, which had a certain fuzziness to it, but then you were shooting it in HD so it had that different look. Matt was really the innovator in terms of that.

But as far as rhythm, music, storytelling, all of that is about filmmaking rather than reporting. I’ll say to people, “don’t wait for money, don’t wait for anybody to say yes to do your project, just go ahead and do the project.” But at the same time, I have fifteen years of experience of making thirty different stage productions that are brand new plays with a group of collaborators and that is a craft that you have to work on. You have to constantly be in contact with your audience to know if the play is working. Is this too long? Is this joke actually funny or do you just think it’s funny? So, in developing GasLand, there is an aesthetic sensibility in terms of the editing, in terms of how we’re creating sound and image, but also a constant engagement with the audience. We showed the first ten minutes seventeen times, we showed half an hours worth to audiences. And part of that was also engaging the [anti-fracking] movement and letting them know that we were doing the project and making sure that they were with us. But the other part of that was also finding out, did the audience respond to the voice over? Did they think this was funny? Was this too long? You can feel the energy in the room. As a theater person, I’m there every night and I’m making changes every night, because you have to adjust until you get to the point where it’s going to work completely all by itself. With film it’s funny because it can go to so many more people, at the same time, I don’t think filmmakers screen nearly enough while they are in process. There is this idea that you have to keep it all secret. We had forty-five minutes of the movie up on the internet for a year before Sundance. It was running under a different title, it hadn’t all been compiled and pulled into one coherent film, but we knew what worked and what didn’t work and those decisions were crucial. I didn’t know I was going to be in the movie. We didn’t know for sure if it was going to be a road movie or if it was going to be a mash up of all these different places. But we found the audience responded to the voice-over, responded to the character, responded to these different journeys and that’s all because we were constantly screening and constantly showing it to people — for political reasons, but then also, of course, it did help the film.

But as far as rhythm, music, storytelling, all of that is about filmmaking rather than reporting. I’ll say to people, “don’t wait for money, don’t wait for anybody to say yes to do your project, just go ahead and do the project.” But at the same time, I have fifteen years of experience of making thirty different stage productions that are brand new plays with a group of collaborators and that is a craft that you have to work on. You have to constantly be in contact with your audience to know if the play is working. Is this too long? Is this joke actually funny or do you just think it’s funny? So, in developing GasLand, there is an aesthetic sensibility in terms of the editing, in terms of how we’re creating sound and image, but also a constant engagement with the audience. We showed the first ten minutes seventeen times, we showed half an hours worth to audiences. And part of that was also engaging the [anti-fracking] movement and letting them know that we were doing the project and making sure that they were with us. But the other part of that was also finding out, did the audience respond to the voice over? Did they think this was funny? Was this too long? You can feel the energy in the room. As a theater person, I’m there every night and I’m making changes every night, because you have to adjust until you get to the point where it’s going to work completely all by itself. With film it’s funny because it can go to so many more people, at the same time, I don’t think filmmakers screen nearly enough while they are in process. There is this idea that you have to keep it all secret. We had forty-five minutes of the movie up on the internet for a year before Sundance. It was running under a different title, it hadn’t all been compiled and pulled into one coherent film, but we knew what worked and what didn’t work and those decisions were crucial. I didn’t know I was going to be in the movie. We didn’t know for sure if it was going to be a road movie or if it was going to be a mash up of all these different places. But we found the audience responded to the voice-over, responded to the character, responded to these different journeys and that’s all because we were constantly screening and constantly showing it to people — for political reasons, but then also, of course, it did help the film.

Could you talk about the narration, the quality of your voice and how you recorded the narration?

JOSH FOX: Originally, I was just using the lav mic, and then Matt Sanchez said that the mic wasn’t so good and that he’d bring in another one. I did most of the voice-over between two and four in the morning. I don’t think I wrote anything down. It was a matter of speaking the events of that day as I was re-watching that day unfold on the camera. The first opening sequence — eight minutes — there were two different versions of that. Mostly it was about finding ways to tell a story about a character as fast as possible. Lewis Meeks for example, he comes through so loud and clear, he’s just amazing. I wanted to make sure that people would see these amazing 70’s mirrors in his house and his buffalo couch and so when I say, “I like Lewis immediately…there these cool 70’s patterned mirrors , cowboy statues everywhere, and then the most comfortable couch in the United States.” And then we show this buffalo tail at the end of the couch and you know that that’s going to be funny. I think that’s your job, to frame things in a way that is both revealing and honest, but also engaging to the audience so you know you’re going to get a laugh. I think laughs are very important. When you watch GasLand people are laughing all the way through the movie. And the reason that’s important is because you’re entering through a different door. You have to have people’s open heart and open mind, you know? And also this idea of the detective story that comes out in the film. We did talk about it, but then it was never a question of writing things down on a piece of paper. It was like, all right, here’s the camera, there’s the mic, and let’s talk right now and let me see what I can say. And then naturally I think subject headings come to you. “Anatomy of a Gas Well” for example. We knew we wanted to go through all the different pieces of the gas wells and how are we going to do that? Are we going to do that in several different interludes as we go through? We found that when we got to Pinedale — the section where we’re in the biggest gas  field – it’s just easy to go through the whole “Anatomy of a Gas Well” right there. So, it’s all very spontaneous and about listening to it as a performance in a way, but also as a document. I couldn’t recreate the voice-over. We tried to go back into the studio and rerecord all of it. Because, well, the sound recording was not so good. I was like, “well, I don’t know, it sounds O.K.” But then Trish, our producer suggested I go into a real studio and just re-record everything. So I went into a real studio and re-recorded everything. And it sucked. It was awful. I did it at nine in the morning. There was a technician there, there was a fancy microphone, it cost us tons of money and guess what? The thing that was homemade was better. Homemade works. Sometimes that professional atmosphere can get in the way of what you really want to do and say. I write all my plays between midnight and 4am. You’re just a lot less censored at that moment. Sometimes those three in the morning ideas are the best ideas. You know, some of that did have to get re-done, because I sounded so tired that it was bad. But that was the process for that.

field – it’s just easy to go through the whole “Anatomy of a Gas Well” right there. So, it’s all very spontaneous and about listening to it as a performance in a way, but also as a document. I couldn’t recreate the voice-over. We tried to go back into the studio and rerecord all of it. Because, well, the sound recording was not so good. I was like, “well, I don’t know, it sounds O.K.” But then Trish, our producer suggested I go into a real studio and just re-record everything. So I went into a real studio and re-recorded everything. And it sucked. It was awful. I did it at nine in the morning. There was a technician there, there was a fancy microphone, it cost us tons of money and guess what? The thing that was homemade was better. Homemade works. Sometimes that professional atmosphere can get in the way of what you really want to do and say. I write all my plays between midnight and 4am. You’re just a lot less censored at that moment. Sometimes those three in the morning ideas are the best ideas. You know, some of that did have to get re-done, because I sounded so tired that it was bad. But that was the process for that.

There’s a certain thing, though, that I can’t possibly impart to people, which is the way my brain works. Sometimes I just know that something’s going to be funny. Like was in Washington, D.C., Capitol Hill, yesterday taping interviews with Dennis Kucinich, Jared Polis and Rush Holt and we were down in the cafeteria and the cafeteria is in the middle of a cheese festival. And there are all these little cards on the table that are like, “CHEESE!” And I thought they were funny, you know? And they had nothing to do with the story. And then there was also a heading over the cafeteria that said “wraps” and sign the said “members only”. It was like the members only wraps. It might not be funny when you get down the line, but when you’re sitting there and it strikes you as odd, you have to shoot it as a thought that in the middle of this sober D.C. segment we’ll go into the cafeteria and talk about how the food is really crappy in congress.

I often like to tell a joke when I walk into somebody’s house. At least say something funny or something nice. If you’re going to be with a subject and all of the sudden you’re sharing their sense of humor, then you know everything’s fine.

Let them know that it’s okay to have a good time while we’re doing this, even if it’s the most horrible subject. Even if their house is about to explode or they have cancer. You still have to let people know that they’re going to have a good time doing this. And that you can relate to them as a human being. And if that means they’re having a beer, have a beer. There was this one time when I drove up to talk with Kim Weber — she’s the woman in Colorado who has lesions in her brain — I drove up to her house and, like, fifteen dogs attack my car. All these big black dogs jumping all over the car. Okay, there were four of them, but it seemed like it was fifteen. And I’m like, “oh, what’s this one’s name, baby killer?” And then she’s laughing. And then all of the sudden, you’re sitting there, she’s doing this interview with me and she’s able to open up in a way maybe she wouldn’t have. You see the person to a greater degree, than if they’re just officially sitting down and doing the interview.

The other question is always when do you turn on the camera. I never turn on the camera until I feel like I know the people. And that can happen in five minutes. But only in rare instances will I turn the camera on before I’ve looked people in the eye and told them who I am and I’ve explained what I’m doing and they know what’s up. I just think comfort level with people is extremely important. Because then things happen. It’s life. You’re not just documenting the issue.

With many of the official figures in the film, it seemed like you had the camera running the moment you entered the room.

JOSH FOX: That’s different. I think in an official capacity you roll before you walk into the office and you don’t stop rolling until you’ve left the office, even if you say thank you very much, you still roll and roll and roll. It’s totally different. Not that you want to do anything that is cheep or to put anything in that is off the record, but in certain cases, for example with Dave Neslin of the Colorado Oil and Gas Conservation Commission, we had an appointment. He knew what we were there for. We handed him our release form because he’s sort of a middle figure. He not a public official in the same way that you have a congressman or a secretary of a department. So we weren’t sure if we had to have a release from him. So we gave him the release. And we’re rolling the whole time because that was a hostile situation. These are guys who are apologists for the gas industry, who are justifying, both in science and in policy, the systematic destruction of people’s houses, neighborhoods, and health. And then of course, we get kicked out. And it’s like, how are you kicking us out, we have an appointment? It doesn’t make any sense. And then they turn around later and says that if I had interviewed with Dave Neslin he would have cleared up a bunch of stuff. And I was like, we were there, in the office. So they’re actually a government agency that is blatantly lying. And if you have that suspicion, then go ahead, you don’t have to tell people you’re shooting. You have to get the story and if the story is that you suspect that there is some kind of big lie that is happening, you do have to investigate that. And it is tricky and it is dangerous. I mean there’s a very fine line. You don’t want to [intentionally] embarrass someone. At the same time, when you watch the opening of Fahrenheit 911 and you have all the preparation moments of the Bush administration, John Ashcroft getting his make-up on and Wolfowitz spitting on his eyebrows. It is so revealing of who those people are. It’s cheap, but it’s perfect. You’re talking about staging a war and creating an image so that you can essentially kill lots of people, so you have to have those moments of Ashcroft and Wolfowitz because that’s all right there. But I think with walking into people’s homes who are not acting in an official capacity, who are not part of that great theatrics of government, it’s a whole different thing. There is a division between what’s really personal and what’s public persona or a person who is operating in a public sphere.

When you started out did you have a clear sense of what sort of impact you wanted to have with the film and did your goals for impact change as the film progressed?

JOSH FOX: Well…I wanted to do something to find out what was going on. This [gas drilling] was a huge transformative proposition for a huge area of New York and Pennsylvania. I didn’t know how extensive it was, you find out as you go along. I didn’t know if I was making a five-minute YouTube video for people to have education or twenty minutes or a feature at first. The impulse was to address the issue, to address the crisis and find out what was really the truth. Was it how the environmentalists said it was or was the industry correct and it was all going to be fine. I had my suspicions, but I wasn’t sure. You have to question everything, everything that everybody is saying and try to find out your own version of what the truth is. But then once we realized that we were making a feature film, we want it to have the same amount of attention that other effective feature documentaries have. I don’t know what I was thinking. I didn’t know anything about film distribution. I didn’t know anything about how that all works. I didn’t understand what a sales agent was until we got to Sundance because I refused to pick up the phone until we finished the movie and we finished the movie the day before Sundance. I mean we showed up the day of Sundance starting and they were like, “how are you going to sell this movie?” And I’m like, “sell the movie, it’s mine, I don’t want to sell it!” You know, didn’t understand any of this. But you find out everything you need to find out at every stage of the game. And I think that it was much more important not to answer the phone even though Sony Pictures Classics was calling and CAA was calling and all these people were calling. I was like, “we’re not finished with the movie, I’m not talking to you yet.” And we were really in a race to finish the movie, because I was also directing a play that was at the same fucking time, January of 2010. We had a play opening on January 5th and it was running on Lexington Avenue and 25th Street and our sound studio luckily was on 6th Avenue and 25th Street. So I was running back and forth between the theater and the sound mix and sleeping in the sound studio and we weren’t finished editing. We literally handed it off to the sound mixer in sections because we hadn’t finished huge sections. We didn’t watch the film before Sundance.

But to get back to the original question, what’s really key about impact has nothing to do with whether or not the film was on HBO alone. You have to work. You have to go out and do the basic stuff that everyone hates to do, which is the activist work, which is boring. And don’t tell me you can’t do your next project and do that. We’ve been making GasLand II and a project about renewable energy at the same time as touring to 110 different cities around the United States working with three hundred or so grassroots organizations on the ground locally and all the major national environmental organizations, and Washington, DC and the city of New York and the city of Pittsburgh and Austin. It’s about how many people can we reach, how much information can I give out. Beside the film, there’s Q&As, interviews, appearances on television, all of that stuff. It’s very hard for me to separate right now. The film itself and what I do every day. I think it’s 12 or 15 appearances on CNN, it’s the Daily Show, it’s every NPR program on the face of the earth, because it’s an issue that’s right now going to determine the make up, the character of the entire northeast of the United States and the energy future for the planet. So it’s a big issue and it involves as many people and as many places as you can go, but you have to be prepared, I think, and very disciplined about how you’re going to speak about it and where. What’s important is figuring out how to screen the film in as many communities in as many places as possible. That’s where the impact really comes from. I basically yelled at Steve James at True/False last weekend after the screening of his new film The Interrupters when he said that he couldn’t show up at all the screenings because he was working on another film and needed to be at home to raise his kids. Those are valid points, but you know, if U2 puts out a record, they’re going to go tour for a year. So why aren’t documentary filmmakers–why aren’t all filmmakers–thinking this way? Mark Ruffalo just put up a tweet “I spent six days making The Kids Are Alright and eight months promoting it.” You’ll go to Sundance or you’ll go to a big festival and then, if you’re lucky, someone will want the film and they’ll put it out there. And then you’ll go “all right, well maybe I’m done.” Wrong. We’ve been touring with GasLand and showing it to audiences as a part of the mission from before the film was finished until now three years later. And that’s why we have an impact. And because we’ve connected with all the people who are working on the issues. We’ve had an impact because we wanted to have an impact, not because we wanted to make a movie.

In terms of making an impact with the film, can you say more about identifying and working with partners?

JOSH FOX: With GasLand, I had just toured all over the United States so I knew the heads of all the major movements who were on the ground working on drilling and they knew me. And that was part of the ambition of the project, to be a connective tissue between these different regions of the United States. And then of course, the bigger national organizations got involved, the Oil and Gas Accountability Project, NRDC, Sierra Club, Environmental Working Group, Earth Justice, Food and Water Watch. They all came to us. But the initial impulse was wanting to tour with the film. I want to barnstorm through New York and Pennsylvania. Now that we know the people on the ground, we’ll call them up and if they can find us a venue and can promote it, we’ll do an event. The first event was so amazing. It was in Williamsport, Pennsylvania and a group called The Responsible Drilling Alliance had put together a screening. It was in April of last year on a Tuesday night and it was raining and I show up and they’d booked this 2000 seat opera house. I was like “oh, boy.” And I said to Ralph Kisberg, the organizer, “If a hundred people show up I’ll be really happy.” And he goes, “We think there’s gonna be more.” And I was like, “O.K., we’ll see.” Sixteen hundred people showed up to watch the film on a rainy Tuesday night. And I, myself, didn’t send out a single advertisement, they showed up because their whole community is being invaded. Then we had one thousand people in Pittsburgh, seven hundred in Syracuse, six hundred people in Elmira, four hundred people at. And they organized all of it.

And all this was two or three weeks before the HBO premier. A lot of people advised against that, they said “you’re crazy, you can’t put it into movie theaters before it’s run on HBO!” And we were like, “well, we think we can.” It’s something HBO doesn’t usually do but we explained why it was important and they agreed. The box office really depended on where we screened. In New York, we did terrific. We sold lots of tickets in Dallas. In California, where nobody knows about the issue and we had no advertising dollars, we bombed. Completely bombed. So you have the nights where you have sixteen hundred people show up on a Tuesday in the middle of Pennsylvania and then you open the film at the art house in San Diego and two people come. When you’re in theaters you really do need to have an advertising push, but that can come from the communities you’re working with.

What is a successful documentary theatrical run for your film? Is it one hundred thousand people, two hundred, five hundred? You know, how many people are actually involved in the issue you’re working on in a skin in the game kind of way? With GasLand, we have millions who are actually involved, we know that. So the tour was crucial for us, that’s what created the impact. It was about connecting the dots and it originally came from the mission of the project, which was to do as big a comparative analysis [of fracking] in as many different states as we could and that that led organically to knowing all the grassroots organizations and then working with the bigger nationals organizations.

Have you had to bring on additional staff to help with the outreach effort?

JOSH FOX: We had three different coordinators over the summer, who were grassroots coordinators, people who do that for a living, we had funding from the Park Foundation and from the Fledgling Fund and the 11th Hour Fund. That was crucial. That paid for travel, that paid for a coordinator, that paid for our website, some of those very fundamental tools that you need. But even without all that, you could go ahead and do this. Our screening fee was two or three hundred dollars no matter how many people came. And if they couldn’t raise two hundred dollars, we were like, “all right, fine.” We didn’t make anything on it. We just basically kept going. Right now, we have forty more screening lined up with no funding. We have run out of all of our funding, but I wend to a guy named David Braun from United for Action who had a good knowledge of the field and good judgment and I said, alright, you want to see change, I want to see change, lets get the film out there again. We’ve run out of money to pay our coordinator, but if you book the film, you can take fifty percent of the screening fee for United for Action and we’ll take the other fifty percent to keep our operations running and pay our one part-time staff person. David has booked forty screenings in the last two weeks. I don’t know, probably some of the screening fees are two hundred, some of them are three hundred, some of them are fifty dollars some of them are zero. But he’s making enough there to keep his organization going. The other grassroots organizations are happy because they are going to be able to raise funds wherever the film is showing, so it all works. So, even if you don’t get grant funding, it is possible to get your film out there. The mindset that you have to have is that no one cares about this film and this issue but me. Then if you do find other people who care about it, great, they’ll help, but you always have to have the mindset of nobody cares about this but me. I have to make people care about it. And even if no one cares about it, I will get the movie out there to a couple hundred thousand people. You can do that. Even if it means you throw it up on the Internet. We’ve had probably more torrents and more uploads to YouTube than anybody and for the last three weeks we were the top selling DVD in documentary and then we number four right after Inside Job and Waiting for Superman had just come out. All the copies of the film that have been stolen and download and bootlegged and distributed throughout the land, all of that helps you. That’s advertising. The more people who know about the movie the better. It does scare the shit out of distributors to have torrents flying all over the place. We didn’t get the deal with Sony Pictures Classics who were interested in distributing the film because they said “well, it’s an activist documentary and people are going to download it and steal it.” For them it’s scary. But I think the more people who know about a film the better, no matter what form it is. I don’t think it hurts your sales or anything like that.

Since getting the film seen as much as possible was so important, did you have to be careful not to lock up all your rights with any one distributor?

JOSH FOX: Initially I was completely inexperienced with distribution. I didn’t know anything about what went into the sale of a movie. What first came to us was the international piece, which was weird, but once we sold that we couldn’t go into an all rights deal with anybody. But I didn’t really like the idea of all the eggs being in one basket. I really liked getting New Video as a DVD distributor. That’s their specialty and they were great at that. And then HBO was very, very attractive even though it would have been conceivably way less money than if we’d ended up having a successful theatrical run. But it didn’t matter, with forty million subscribers, getting broadcast on HBO changes the game over night. Once it aired and you had millions of people watch it, you knew that all of the sudden, things were going to change. And HBO’s PR machine was also really fantastic. And they treated us kind of special. We said, we really need you to treat us special if we’re going to give this to you. And they did. They hired a whole extra publicity firm, they got me on the Daily Show, all of this kind of thing happened because of HBO. But the great thing about it was that we also controlled the theatrical. We could screen it whenever we wanted to. And that was all up to us. I’m a theater person, I wanted to have the ability to show the film wherever I wanted to. So, it’s a tradeoff. I think you have to find the best deal you can that allows you to get the film to the most people. But, like I said, you care about it way more than the distributor cares about it, I hope. So I think you have to be a little bit worried about how the [distributor] is going to handle it. You don’t want to develop a bad relationship with anybody. We have a great relationship the people at HBO and New Video, because they know we are going to work our asses off and we’re going to be polite and nice people. But at the same time, yes, I think you have to take as much of it on as you can.

So we don’t have a lot of time left, and we didn’t get a chance to ask you about editing.

JOSH FOX: Oh, yeah. Well, you really should talk to Matt Sanchez, the editor. We worked side-by-side for a year.

Did using so many different cameras and camera people, make it difficult to maintain a cohesive style in the editing room?

JOSH FOX: Well, I actually don’t know the answer to that. I don’t know how the hell it comes out looking coherent, because it’s so not coherent. I mean it’s all over the place, but you don’t notice. I do think chapters help, the structure of moving state-to-state helps. Shooting on different cameras also helped. For example, the PD150 is grainy out of focus, but emotionally beautiful. And it will come in at a moment when you need that. You’ll interrupt a sit down interview maybe with these subjective shots. You’ll find that it’s not about cameras, it’s about the fluidity of different shots and you’ll find a certain shot will match where as another one doesn’t. I don’t know if you ever saw the original Ren & Stimpy show. In the original Ren & Stimpyshow there’s the cheep animation where they’re moving and then there are these stills which are incredibly detailed and beautiful and they just would cut to them and then focus in and then cut right back out to crappy animation and it works. It’s like you’re opening up a door or looking through a microscope for a second. I think it’s just about playing with the material. I would never shot with just one camera. Because even a genius only has a seven-minute attention span and most of us are around three or four minutes so, you have to constantly be reinvesting your audience over and over again. And with GasLand’s style, people complain that it’s too shaky and out of focus. They’re awake though. They’re annoyed, maybe. But they’re awake. Matt Sanchez and I had a little piece of paper taped in the editing room with the letters W.W.G.D. It stood for “what would Godard do?” For example, there were times when Matt and I would intentionally cut a shot or the music at the wrong place. Or you see this doorknob here? Let’s say I’m walking through the door on the way to an interview and the doorknob is working totally normally. I would never think about the doorknob, I’d be thinking about the interview. But if the doorknob is busted, if I’m jiggling it and can’t get it open, suddenly, the doorknob is alive and I remember it. It’s the same with film.