This white paper lays out an expanded vision for “public media 2.0” that places engaged publics at its core, showcasing innovative experiments from its “first two minutes,” and revealing related trends, stakeholders, and policies. Public media 2.0 may look and function differently, but it will share the same goals as the projects that preceded it: educating, informing, and mobilizing its users.

February 2009

Click here to view or download a PDF of this report.

Report by:

Jessica Clark,

Research Director, Future of Public Media Project, Center for Media & Social Impact, American University

Pat Aufderheide,

Co-Director, Center for Media & Social Impact, American University

With funding from:

The Ford Foundation

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Public broadcasting, newspapers, magazines, and network newscasts have all played a central role in our democracy, informing citizens and guiding public conversation. But the top-down dissemination technologies that supported them are being supplanted by an open, many-to-many networked media environment. What platforms, standards, and practices will replace or transform legacy public media?

This white paper lays out an expanded vision for “public media 2.0” that places engaged publics at its core, showcasing innovative experiments from its “first two minutes,” and revealing related trends, stakeholders, and policies. Public media 2.0 may look and function differently, but it will share the same goals as the projects that preceded it: educating, informing, and mobilizing its users.

Multiplatform, participatory, and digital, public media 2.0 will be an essential feature of truly democratic public life from here on in. And it’ll be media both for and by the public. The grassroots mobilization around the 2008 electoral campaign is just one signal of how digital tools for making and sharing media open up new opportunities for civic engagement.

But public media 2.0 won’t happen by accident, or for free. The same bottom-line logic that runs media today will run tomorrow’s media as well. If we’re going to have media for vibrant democratic culture, we have to plan for it, try it out, show people that it matters, and build new constituencies to invest in it.

The first and crucial step is to embrace the participatory—the feature that has also been most disruptive of current media models. We also need standards and metrics to define truly meaningful participation in media for public life. And we need policies, initiatives, and sustainable financial models that can turn today’s assets and experiments into tomorrow’s tried-and-true public media.

Public media stakeholders, especially such trusted institutions as public broadcasting, need to take leadership in creating a true public investment in public media 2.0.

Takeaways

• Public media 2.0’s core function is to generate publics around problems.

• Many-to-many digital technologies are fostering participatory user behaviors: choice, conversation, curation, creation, and collaboration.

• Quality content needs to be matched with effective engagement. Public media projects can happen in any venue, commercial or not.

• Collaboration among media outlets and allied organizations is key and requires national coordination.

• Taxpayer funds are crucial both to sustain coordination and to fund media production, curation, and archiving.

• Shared standards and practices make distributed public media viable.

• Impact measurements are crucial.

Action Agendas

• Public media institutions and makers need to develop a participatory national network and platform; to cross cultural, social, economic, ethnic, and political divides; to collaborate; and to learn from others’ examples, including their mistakes.

• Policymakers need to create structures and funding to support national coordination of public media networks and funding for production, curation, and archiving; to use universal design principles in communications infrastructure policy and universal service values in constructing and supporting infrastructure; to support lifelong education that helps everyone be media makers; and to build grassroots participation into public policy processes using social media tools.

• Funders can invest in media projects that build democratic publics; in norms- setting, standardization of reliability tools, and impact metrics; and in experiments in media making, media organizations, and media tools, especially among disenfranchised communities.

INTRODUCTION

In the post–World War II boom, the shallowness and greediness of consumer culture appalled many people concerned with the future of democracy. Commercial media, with few exceptions—such as some news beats in prestige newspapers—mostly catered to advertisers with lowest-common-denominator entertainment. How could people even find out about important issues, much less address them?

In the United States, this concern inspired such initiatives as the Hutchins Report of the Commission on the Freedom of the Press (1947), the Carnegie Commission on Public Broadcasting (1966), the Poynter Institute (1975), and other journalistic standards and training bodies. Foundations also supported media production and infrastructure, including the Ford Foundation’s commitment to public broadcasting, the Rockefeller Foundation’s investment in independent filmmakers, and the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation’s funding of media arts centers. Some corporations also created public media for a mass media era: For instance, the burgeoning cable industry offered C-SPAN as a service particularly interesting to legislators. Guided by public interest obligations, broadcasters supported current affairs programming and investigative reporting. Taken together, these efforts placed the onus of educating, serving, and enlightening the public on media makers and owners. They secured the public stake through regulation, tax exemptions, and chances for citizen review.

Public media 1.0, like parkland bordering a shopping mall, inhabited a separate zone: public broadcasting, cable access, nonprofit satellite set-asides, national and international beats of prestige journalism. These media played occasional major roles (showcasing political debates; airing major hearings; becoming the go-to source in a hurricane) while also steadily producing news and cultural enrichment in the background of Americans’ daily lives.

Throughout the second half of the twentieth century, public media 1.0 was widely accepted as important, but rarely loved—politely underfunded by taxpayers, subsidized weakly by corporations, grudgingly exempted from being profit centers by shareholders. It was often hobbled by the inevitable clash between democratic debate and entrenched interest. In public broadcasting and in print journalism, partisan and corporate pressures distorted—even sometimes defanged—public discussion. Cultural battles sapped government funding for socially relevant arts and performance. Public media 1.0 was also limited in generating vigorous public conversations by the one-to-many structure of mass media. Broadcast town hall forums with representative citizens; op-ed pages where carefully selected proxies air carefully balanced views; ombudsmen; and talk shows all created limited participation. But print and broadcast are inevitably top-down. And then came the Internet, followed by social media. After a decade of quick-fire innovation—first Web pages, then interactive Flash sites; first blogs, then Twitter; first podcasts, then iPhones; first DVDs, then BitTorrent—the individual user has moved from being an anonymous part of a mass to being the center of the media picture.1

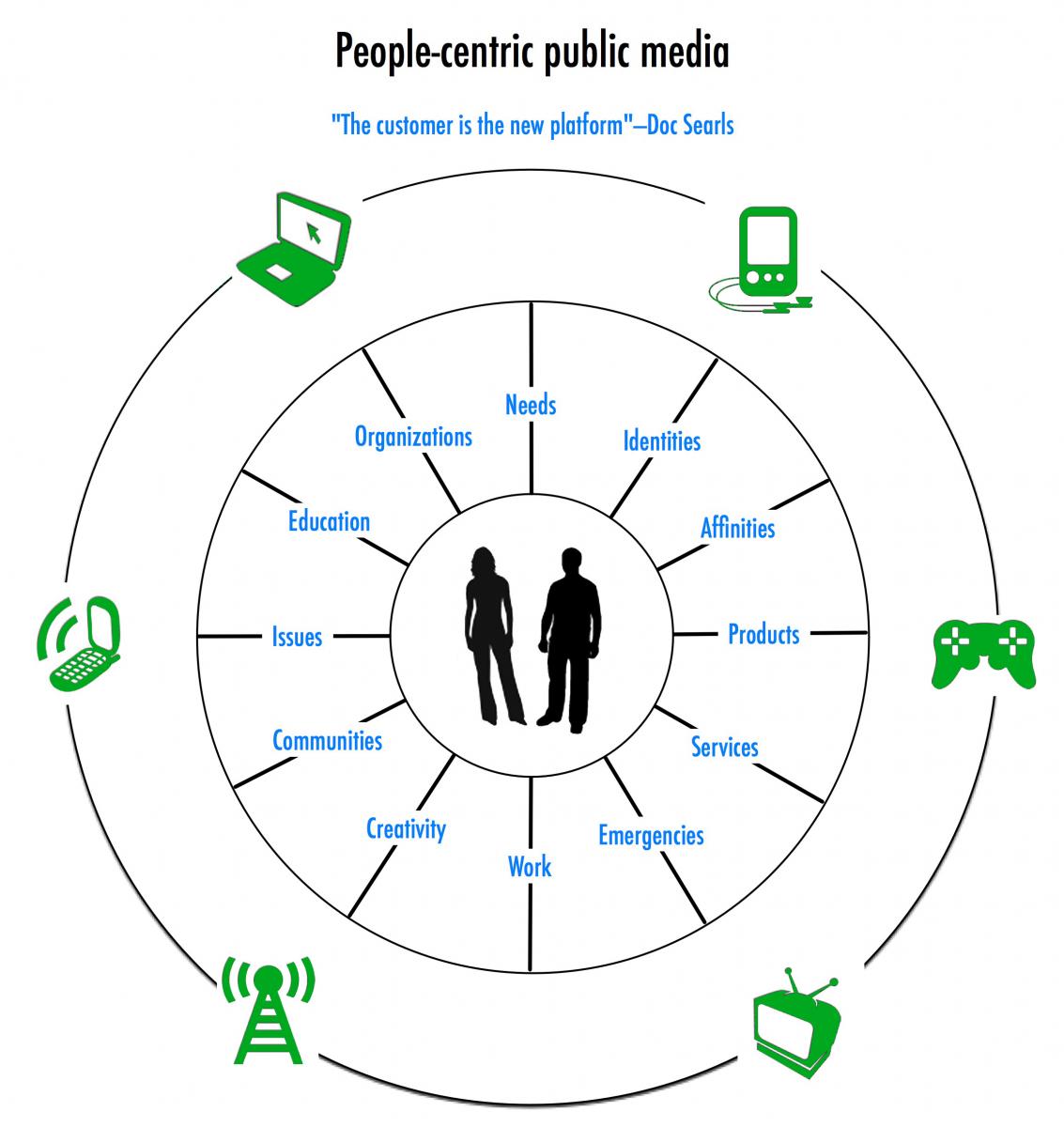

| The people formerly known as the audience now are at the center of media. |

Commercial media still dominate the scene, but the people formerly known as the audience are spending less time with older media formats. Many “digital natives” born after 1980 (and a number of us born before) now inhabit a multimedia-saturated environment that spans highly interactive mobile and gaming devices, social networks, chat—and only sometimes television or newspapers. People are dumping land lines for cell phones and watching movies and TV shows on their computers. Not only is much more content now available free, but advertisers are migrating online with it, supporting new media players, such as search engines and social networks. Open platforms for sharing, remixing, and commenting upon both amateur and professional media are now widely popular—hastening the demise of print subscriptions and “appointment television.” 2 While broadcast still reaches more people, the Internet (whether accessed through phones, laptops, or multimedia entertainment devices) has become a mass medium.3 New business models are emerging, grounded in participation by users.4 Changing media habits have transformed everything, from bookselling to politics. The 2008 election was a dramatic example of the power of participatory media harnessed to political action.5 Connectivity, participation, and digital media creation will only increase. Broadband access is growing and may expand further with FCC-permitted access to unlicensed “white spaces” in the spectrum, and with community projects to increase wireless and fiber-optic access. Digital audio and video recorders, laptops, and Web-enabled mobile phones are only getting cheaper and more sophisticated. And Web 3.0 is on the way, featuring “semantic” technologies that will automatically filter user input to create more accurate. and meaningful search experiences.6 |

Here are five fundamental ways that people’s media habits are changing:

Choice: Rather than passively waiting for content to be delivered as in the broadcast days, users are actively seeking out and comparing media on important issues, through search engines, recommendations, video on demand, interactive program guides, news feeds, and niche sites. This is placing pressure on many makers to convert their content so that it’s not only accessible across an array of platforms and devices, but properly formatted and tagged so that it is more likely to be discovered.

Conversation: Comment and discussion boards have become common across a range of sites and platforms, with varying levels of civility in evidence. Users are leveraging conversation tools to share interests and mobilize around issues. 7 Distributed conversations across online services, such as Twitter and FriendFeed, are managed via shared tags. Tools for ranking and banning comments give site hosts and audiences some leverage for controlling the tenor of exchanges. New tools for video-based conversation are now available on sites such as Seesmic. News is collaboratively created, gaining importance by becoming part of electronic conversation.8

Curation: Users are aggregating, sharing, ranking, tagging, reposting, juxtaposing, and critiquing content on a variety of platforms—from personal blogs to open video-sharing sites to social network profile pages. Reviews and media critique are popular genres for online contributors, displacing or augmenting genres, such as consumer reports and travel writing, and feeding a widespread culture of critical assessment.

Creation: Users are creating a range of multimedia content (audio, video, text, photos, animation, etc.) from scratch and remixing existing content for purposes of satire, commentary, or self-expression—breaking through the stalemate of mass media talking points. Professional media makers are now tapping user-generated content as raw material for their own productions, and outlets are navigating various fair use issues as they wrestle with promoting and protecting their brands.

Collaboration: Users are adopting a variety of new roles along the chain of media creation and distribution—from providing targeted funds for production or investigation,9 to posting widgets10 that showcase content on their own sites, to organizing online and offline events related to media projects, to mobilizing around related issues through online tools, such as petitions and letters to policymakers. “Crowdsourced” journalism projects now invite audience participation as investigators, tipsters, and editors—so far, a trial-and-error process.

These five media habits are fueling a clutch of exciting new trends, each of which offers tools, platforms, or practices of enormous possibility for public media 2.0:

Ubiquitous video (choice, creation, collaboration)

Professional and amateur video alike are migrating online to sites such as Hulu and YouTube; nonprofessional online video is becoming part of broadcast news and newspaper reporting; live streaming and podcasting are routine aspects of public events.

Powerful databases (curation, creation)

Deep wells of data and imagery are increasingly valuable for reporting, information visualization, trend-spotting, and comparative analysis. Databases also now serve as powerful back-ends for managing and serving up digital content, making it available across a range of browsers and devices.

Social networks as public forums (conversation, collaboration)

Durable social-networking platforms, such as Facebook, and on-the-fly social networks, such as the open-source Ning, allow multifaceted media relationships with one person, a few, or many people.

Locative media (choice, creation)

GPS-enabled mobile devices are allowing users to access and upload geographically relevant content, and a new set of “hyperlocal” media projects are feeding this trend. Conversely, maps are becoming a common interface for news, video, and data.11

Distributed distribution (choice, curation)

News feeds, search engines, and widgets are allowing content to escape the traditional boundaries of the channel or site. Users are coming to expect access to anywhere, anytime searchable media.

Hackable platforms (creation, collaboration, curation)

Open source tools and applications are becoming increasingly customizable. Media makers can tailor their platforms, sharing tips across a broad community of developers, and users can pick and choose how they will interact with content.

Accessible metrics (creation, curation)

Ranking and metrics sites, such as Google Analytics, Alexa, and Technorati, make it easier for media makers to compile and compare their audiences—and for outsiders to more easily judge and note success.

Cloud content (choice, creation)

Applications, media, and personal content are migrating away from computers and mobile devices and onto hosted servers—into “the cloud” of online content. On the one hand this offers simplicity, easy sharing, and protected backups; on the other, it threatens control and privacy.

Pervasive gaming (choice, collaboration)

Gaming—playing computer, Web, portable, or console games, often connecting with other players via the Internet—has become as ubiquitous as watching TV for young people. 12

|

The initial period of individualistic experimentation in participatory media is passing, and large institutions—including political campaigns, businesses, universities, and foundations—are now adopting social media forms, such as blogs and user forums. With greater use comes consolidation in tools, applications, platforms, and ownership of them. YouTube and Blogger are now owned by Google, Flickr is owned by Yahoo; WordPress, Facebook, and Twitter are all in play. Every step of consolidation is also a step in path dependence. That forecloses options, creates powerful stakeholders, and also establishes new, much-needed business models. Of course, as new business models emerge, the heady days of experiment will cede to the familiar terms of power and profit. Some media and legal scholars see big trouble in this consolidation. Jeff Chester thunders against corporate greed; Jonathan Zittrain fears that Apple will make our digital lives easy by taking away our creative choices; Siva Vaidhyanathan fears that Google’s tentacles will reach into every aspect of our lives while making it ever easier for us to do our work with its tools; Cass Sunstein is sure we’re losing our social souls. Public media 2.0 can develop on the basis of the platforms that are the winners of the consolidation taking place today and with the help of policy that supports it within that environment. But it won’t happen by accident. Commercial platforms do not have the same incentives to preserve historically relevant content that public media outlets do. 13Building dynamic, engaged publics will not be a top agenda item for any business. Neither will tomorrow’s commercial media business models have any incentive to remedy social inequality. Participation that flows along today’s lines of access and skill sets will replicate past inequalities.14 If public media 2.0 looks less highly stratified and culturally balkanized than the public media of today, it will be because of conscious investment and government policy choices. |

Public Media 2.0 won’t develop by accident.

|

PUBLIC MEDIA 2.0: THE FIRST TWO MINUTES

Exciting experiments in public media 2.0 are already happening:

World Without Oil

The Independent Television Service (ITVS), part of public broadcasting, attracted almost 2,000 gamers from 40-plus countries to its World Without Oil (http://worldwithoutoil.org), a multiplayer “alternative reality” game. Participants submitted reactions to an eight-month energy crisis via privately owned social media sites, such as YouTube and Flickr—and made corresponding real-life changes, chronicled at the WWO Lives blog (http://wwolives.wordpress.com).

The Mobile Report

The Media Focus on Africa Foundation worked with the Arid Lands Information network to equip citizen reporters in Kenya with mobile phones. The Mobile Report project used an online map interface to aggregate ground- level reports on election conditions (http://mfoa.africanews.com/site/page/mobile_report).

10 Questions Presidential Forum

Independent bloggers worked with the New York Times editorial board and MSNBC to develop and promote the 10 Questions Presidential Forum (http://www.10questions.com/). More than 120,000 visitors voted on 231 video questions submitted by users. Presidential candidates then answered the top 10 questions via online video. The top question was also aired during the MTV/ MySpace “Presidential Dialogue” featuring Barack Obama.

OneClimate Island

During the United Nations Climate Change Conferences in Bali and Poznan, a news network of nonprofits, OneWorld, connected delegates and participants to reporters and advocates around the world via Second Life, an online 3-D virtual world. The event spawned regular meetings of environmental activists on OneWorld’s virtual OneClimate Island.15

Facing the Mortgage Crisis

As the mortgage crisis hit home in every community, St. Louis public broadcasting station KETC launched Facing the Mortgage Crisis (http://stlmortgagecrisis.wordpress.com), a multiplatform project designed to help publics grappling with mortgage foreclosures. Featuring invited audience questions and on-air and online elements that mapped pockets of foreclosures, the project directed callers to an information line managed by the United Way for further help. Calls to the line increased significantly as a result.

During the transition to the Obama administration, the transition team launched change.gov, a website where people could not only contribute an issue or question for the new administration to tackle but vote on the relevance of others.

What do all of these media projects have in common? They leverage participatory media technologies to allow people from a variety of perspectives to work together to tackle a topic or problem—to share stories and facts, to ask hard questions, and then shape a judgment on which they can act.

People come in as participants in a media project and leave recognizing themselves as members of a public—a group of people commonly affected by an issue. They have found each other and exchanged information on an issue in which they all see themselves as having a stake. In some cases, they take action based on this transformative act of communication.

This is the core function of public media 2.0 for a very simple reason: Publics are the element that keeps democracies democratic. Publics provide essential accountability in a healthy society, checking the natural tendency of people to do what’s easiest, cheapest, and in their own private interest. They are not rigid structures—publics regularly form around issues, problems, and opportunities for improvement—and this informality avoids the inevitable self-serving that happens in any institution. Publics are fed by the flow of communication.

The open digital environment holds out the promise of a new framework for creating and supporting public media—one that prioritizes the creation of publics, moving beyond representation and into direct participation.16

This is the kind of media that political philosophers have longed for. When Thomas Jefferson said that he would rather have newspapers without government than government without newspapers, he was talking about the need for a free people to talk to each other about what matters. When American philosopher John Dewey argued that conversation was the lifeblood of a democracy, he meant that people talking to each other about the things that really affect their lives is what keeps power accountable.When German philosopher Jorgen Habermas celebrated the “public sphere” created by the French merchant class in the eighteenth century, he was noting that when nonaristocrats started to talk to each other about what should happen, they found enough common cause to overturn an order. They all saw ordinary people talking to each other about what matters as what holds the power of corporations and government in a society accountable.

Where is the impulse to make public media 2.0 coming from? The experiments above, drawn from nonprofit, corporate, and governmental sources, arise both from established mass media and from digital newborns. They depend on deep pockets of existing enterprises as well as individual enthusiasm and volunteer effort. They use both proprietary and open source platforms and tools and often involve some kind of advertising.

Legacy public media, both some commercial journalism institutions and public media institutions, are wrestling hard with the challenge of serving their public missions in new and radically different ways. Commercial projects such as CNN iReport (http://www.ireport.com/index.jspa) and the Associated Press Mobile News Network (http://www.ap.org/mobilenews/) encourage users to upload their own reports and images.

At workshops and strategic planning meetings, journalists are brainstorming new titles for themselves, such as “community weavers.” The Knight Foundation has also been underwriting a surge of innovation in community news—the next phase in its historic support of local newspapers.17

Public broadcasters are grappling with participatory challenges both at a national and a local level. The Online NewsHour offers content from the NewsHour with Jim Lehrer and Web-only features that invite interaction. Some public broadcasting producers have developed widgets that showcase user-generated content.18 American Public Media’s Gather.com creates a social network of public broadcasting supporters. The StoryCorps project partners with public radio stations to collect, broadcast, and promote interviews with everyday Americans that reveal societal truths and collective issues. The ITVS Community Cinema screening series (http://www.pbs.org/independentlens/getinvolved/) combines professional storytelling with nonprofessional participation, and long-form mass media with face-to-face interactions—targeting gatherings and online offerings to specific publics.

Some public broadcasting stations, such as Portland’s Oregon Public Broadcasting (http://www.opb.org/), are positioning themselves online as cross-platform, trusted multimedia news producers and aggregators. Others, such as WILL in Urbana, Illinois, are retraining producers in community engagement practices that can guide more responsive and engaged programming. Still others are encouraging direct production of content by audience members, such as the Docubloggers project (http://www.klru.org/docubloggers/) hosted by KLRU in Central Texas.

Public Radio Exchange (PRX) has brokered a partnership between makers and programmers to “make public radio more public,” working to integrate activities around the five C’s:

• Creation: Their site (http://www.prx.org/) allows independent producers to upload radio pieces.

• Conversation: PRX has also launched a social network that connects young radio producers and teachers, Generation PRX (http://generation.prx.org/).

• Choice: Audiences and public radio professionals seek out pieces through search tools and lists sorted by format, topic, and tone.

• Curation: Users can write reviews and create playlists.

• Collaboration: User feedback helps public radio station producers to assess whether they should play the pieces on air or online.

| Matching up the professional and the amateur is a great challenge. |

The result is an extensive, searchable online catalog of independently produced content that was previously inaccessible to listeners and stations —and a new revenue stream and gathering place for makers. Other public media are also adapting, while maintaining traditional mass-media roles. Cable access media centers, such as the Manhattan Neighborhood Network, are experimenting with webstreaming (http://www.mnn.org), collaborating via open source Web platforms. LinkTV’s “Dear American Voter” (http://www.linktv.org/dearamericanvoter) brings people from around the world into conversation about American politics. Outside legacy media, “citizen journalism” is blooming, often with a broad transnational focus.19 Much of it was propelled initially by individual enthusiasm but has found either foundation funding or advertising or both. Political bloggers have built sites that are now advertiser-enhanced institutions, such as Daily Kos (http://www.dailykos.com) or the Huffington Post (http://www.huffingtonpost.com). International Web platforms, such Global Voices (http://globalvoicesonline.org/) and Open Democracy (http:// www.opendemocracy.net/), foster conversation across national and cultural boundaries. Projects such as J-Lab’s Knight Citizen News Network (http://www.kcnn.org/) and the Center for Independent Media (http://newjournalist.org/) offer journalistic training to citizen media makers. New online platforms, such as Wikipedia, One World, and Global Voices, have grown up in the new nonprofit economy fueled by social entrepreneurs and foundations alike and offer previously unimagined ways to engage in public discussion and comment. For instance, the Wikipedia entry on Sarah Palin, created when she was named John McCain’s running mate, became a vibrant public forum, with Wikipedia monitors maintaining order.20 |

What’s working in the highly experimental and unstable public media 2.0 environment? Some trends stand out:

Multiplatforming and engagement as a matter of course

Public media outlets and individual projects are now regularly including offline, online, print, and social media elements, which extend relevance and impact and provide multiple opportunities for publics to form around media. For example, An Inconvenient Truth was in theaters, is available on DVD, and has a companion book. Related downloads include widgets for bloggers, posters, desktop images of changing weather patterns, screensavers, electronic greeting cards, and a teacher’s guide. This trend is driving multiplatform training in journalism schools.21 Media projects are planned with the engagement of publics as a core feature.22 (See “Documentary Films as Public Engagement” below for more examples.)

Data-intensive visual reporting

Highly visual and information-rich sites, such as Everyblock (http://chicago.everyblock.com/) and MapLight (http://www.maplight.org/), demonstrate how information can be culled from a variety of online sources and combined to reveal trends and stories via interactive, user-friendly interfaces.23 So-called “charticles” are also on the rise in both print and online newspapers, mirroring public enthusiasm for creating visual mashups using tools such as Google Maps—see the “Tunisian Prison Map” for an example (http://www.kitab.nl/tunisianprisonersmap/). Micah Sifry of the Personal Democracy Forum calls this “3-D” content (Dynamic, Data Driven).24 Its rise suggests a role for outlets, governments, nonprofits, and universities as trusted curators of valuable data sets.25

Niche online communities

Publics are gathering around sites and outlets to learn and share information around in-group issues, becoming virtual communities. Such sites may be based on a combination of identity and politics—such as Feministing (http://www.feministing.com), which targets young female readers through pop culture analysis, or Jack and Jill Politics, which describes itself as “a black bourgeoisie perspective on U.S. politics” (http://www.jackandjillpolitics.com/). Even openly partisan blogs, like Little Green Footballs (http://littlegreenfootballs.com/weblog/) or MyDD (http://www.mydd.com/), can serve as both communities and as centers of vigorous debate across lines of opinion and belief. Others affinities are based on location—such as the regional communities that cluster around international meta-blog Global Voices,26 or the local blogs featured in the Knight Citizen News Network map (http://www.kcnn.org/citmedia_sites/). Still others hinge on particular issues or communities of interest, such as Moms Rising (http://www.momsrising.org/), which coordinates advocacy campaigns and blogs around policy issues related to motherhood, or Blog for a Cure (http://www.blogforacure.com/), which brings cancer survivors together.

Crowdsourced translation

Projects such as dotSUB (http://dotsub.com) harness volunteer energy to translate public-minded content so that it can travel across national and linguistic boundaries. Documentary films, political speeches, and instructional videos have all been translated by users of this service. Project Lingua (http://globalvoicesonline.org/lingua/) invites readers of the Global Voices site to translate its content. Translators are active in more than 15 languages, including Spanish, French, Serbian, Arabic, Farsi, and Chinese.

Decoupling of public media content from outlets

With business models for outlets flagging, content has acquired a life of its own. Nonprofit projects, such as ProPublica (http://www.propublica.org) and the Center for Public Integrity (http://www.publicintegrity.org), underwrite investigative reporting that can be placed in print or broadcast contexts but also lives online on the projects’ sites. The increasing primacy of search engines and open platforms as interfaces for finding news and information allows new content producers—such as academics,27 advocacy groups,28 and even political campaigns29—to generate widely circulated content addressing public issues. And the rise of tools for online syndication—such as NPR’s recent decision to release its Application Programming Interface (API)—means that even content originally created by an outlet is not destined to stay within its confines.

New toolsets for government transparency

Open online access to government documents and data now offers raw material for both legacy and citizen media efforts. Open Congress (http://www.opencongress.org) invites users to view and comment on bills, track congressional votes, and follow hot issues. Subsidyscope promises to track and analyze spending, loans, and tax breaks associated with the financial bailout (http://subsidyscope.com). The government itself is a key provider of digital transparency projects, such as USAspending.gov (http://usaspending.gov), which allows users to search federal contract and grant data. A coalition of government transparency advocates has crafted a “right-to-know” agenda for the new administration.30

Mobile public media

Mobile devices are becoming increasingly powerful tools for both production and consumption of public-minded text, audio, photo, and video content, especially in developing countries. Common forms of mobile reporting include SMS-based updates on issues and breaking events, “man-on-the-street” photojournalism, election monitoring, and live audio or video streaming. Cell phones are also creating public media access across class lines in the United States.31Projects such as The People’s 311 (http://peoples311.com/) in New York demonstrate how mobile citizen media creation can coalesce into ongoing public media: participants are encouraged to post photos of broken sidewalks, damaged fire hydrants, and other urban blight, supplementing reports to the city’s free 311 phone service.

Pro-am storytelling

Professionals and nonprofessionals are working together via new tools and platforms to craft narratives that inform public issues. Filmmakers such as Deborah Scranton of The War Tapes and Anders �stergaard of Burma VJ: Reporting from a Closed Country have based their films on footage shot by amateur contributors in high-pressure situations.32 Other projects reveal the narratives of groups that have been suppressed, such as Mapping the Third Ward in Houston. (http://www.storymapping.org/thirdward.html), which features personal stories underpinning gentrification, or the National Black Programming Consortium’s Masculinity Project (http://www.blackpublicmedia.org/catalog/channel/masculinity), which features the work of film professionals such as Byron Hurt alongside youth media productions and nonprofessional commentary and contributions. The work of WITNESS, a human rights organization that features video contributions documenting violations around the world, also exemplifies the power of storytelling by combining the strengths of professional and nonprofessional.33

Peer-to-peer public media training

Networks of media outlets, such as OneWorld (http://us.oneworld.net), the Integrated Media Association (http://www.integratedmedia.org/home.cfm), New America Media (http://news.newamericamedia.org/news/), and The Media Consortium (http://www.themediaconsortium.org/), working together to share and assess strategies for producing effective, public-minded content for the digital, participatory environment. Individual producers are also sharing strategies through projects such as Shooting People (http://shootingpeople.org/), an international networking organization for independent filmmakers.

These trends demonstrate a widespread, cross-sector interest in developing and sustaining high-quality public media in the networked environment. But without coordination and sustained investment, the new public media will continue to develop piecemeal and erratically.

Today’s public media experiments, constituting the first two minutes of public media 2.0, struggle with balancing quality with quantity, participation with reliability. Matching up the power of the professional and the amateur—the so-called “pro-am” approach—is a great challenge. Legacy public media continue to be repositories for high-quality journalism, documentary, and storytelling, much of which has come from independent producers. That content is now being fed across platforms and offered to users who use it for discussion, incorporate it into their own work, and share it with friends.

If experimentation leads to investment in sustained national practice, public media 2.0 will ensure that self-expression is not merely more noise in an already cacophonous media environment. It will be an enabler of opportunity, a catalyst for innovation, and an access provider for people who may never before have given themselves permission to make media. In public media 2.0, they will be contributors to media for public life, about the issues that most touch them. Public media 2.0 won’t just provide information; it will also contribute to helping people understand ongoing and complicated issues, both with content and through practices.

DOCUMENTARY FILMS AS PUBLIC ENGAGEMENT

Already practiced in partnering for impact—with activist organizations, universities, public broadcasters—documentarians are now tapping online tools to attract and mobilize publics.

Not in Our Town, Patrice O’Neill

First broadcast as a half-hour special on PBS in 1995, Not in Our Town I told the story of how the people of Billings, Montana—including grassroots activists, elected officials, schools, unions, newspapers, and churches— got together in the face of assaults on Native American, Latino, and Jewish residents to create an initiative that continues as part of the civic life of the city. This model of citizen action—the diversity of which is traced in many more NIOT films—has inspired a nationwide movement. In 2007, leaders from more than 50 towns and cities gathered to share information and discuss the formation of a national organization and the creation of a social networking site.State of Fear: The Truth about Terrorism, Pamela Yates, Paco de Onis, Peter Kinoy

Addressing the anti-terrorist policies of Peru’s Fujimori government, State of Fear became an international platform to discuss suspension of civil liberties under the threat of terrorism. In addition to English- and Spanish-language versions of the award-winning film, a Quechua- language version is being shown in Andean regions where 70 percent of the 69,000 victims of the Shining Path and government terrorism died. The film was translated and used by the democracy movement in Nepal and has triggered discussion in Russia, Morocco, Turkey, and other countries that see analogous situations in their own countries. It played a key role in the movement to return Fujimori to Peru, where he is now on trial. It has recently entered into public discourse—particularly in the Andean region—to contest denials of complicity by the members of the current government. Using Flip video cameras and the film’s Internet platform, Quechua Indians are adding their own stories to current political debate about reparations.Beyond Beats and Rhymes, Byron Hurt

A critique of violence and misogyny in hip-hop, Beyond Beats and Rhymeshas become much more than an award-winning movie. ITVS, which sponsored community screenings nationwide aimed at young audiences, created a comprehensive curriculum that is downloadable on its Web site. In addition to a tour of Historically Black Colleges and Universities, Firelight Films organized a national outreach campaign involving organizations from women’s shelters to Boys and Girls Clubs of America and YO! TV. It is now a part of The Masculinity Project (http://blackpublicmedia.org/project/masculinity), a Ford-funded initiative of ITVS and the National Black Programming Consortium that invites multi-generational voices to discuss issues of race and gender.Lioness, Meg McLagan and Daria Sommers

Lioness, which premiered at the Tribeca Film Festival and was broadcast nationally on the ITVS television series Independent Lens, is designed to stimulate a national dialogue about the shifting role of women in the military. It tells the stories of five female soldiers, sent to Iraq as cooks, mechanics, clerks, and engineers, who became the first women in American history to engage in direct ground combat —a direct violation of U.S. laws prohibiting the assignment of women to armed combat units. The film’s outreach includes screenings on military bases and human rights and community circuits, as well as policy- making venues. Partnerships have been established with veterans service organizations, military families, and groups advocating for better services for returning women and gender equity among veterans.

BUILDING PUBLIC MEDIA 2.0

Public media 2.0 will evolve across the social media landscape, but it will be held together by a combination of four critical features: A trusted national network to coordinate communication and media practices; funding for content creation, curation, and archiving; partnerships among outlets, makers, and allies; and the standards and measurements that providers of public media uphold, whether they are or are not direct participants in the national platform.

Inevitably, coordinating public media 2.0 will take resources, especially anchoring funds from taxpayers. Wikipedia is a lovely exception to the general rule that public media experiments do not usually take off without subsidy and even Wikipedia has foundation backing.34

Leadership

Who will lead the charge to define and support public media 2.0? There are plenty of organizations both in legacy and new social media, as we have noted, that now perform at least experimental versions of public media 2.0. But who will turn those experiments into broadly accepted social habits? That question has already generated a wide range of proposals, from creating a Digital Future Endowment,35 to establishing a National Journalism Foundation,36 to funding a “public media corps,”37 to reviving the Carnegie Commission’s call for a Public Media Trust.38

There are two outstanding needs: for content and for coordination that builds capacity for public participation. We believe it is important to separate these functions in understanding the needs for leadership:

Content has been the glory of mass media, and there already is a deep pool of high-quality content via mass media journalism, public broadcasting, and the many content entities—including a welter of freelancers and independent producers—that serve them. Many of these entities face a grave long-term challenge as old business models collapse. But there are still plenty of them today, from prestige newspapers and magazines to such entities as National Public Radio to such media production houses as Sesame Workshop, Participant Productions, and Kartemquin Films.

What is needed for the future of high-quality content is at least partial taxpayer support for the many existing operations and for innovative new projects. A federal body committed to funding media production would fund both institutions and individuals who make, curate, and archive public media, functioning much as the National Endowments for the Arts and Humanities, the Institute for Museum and Library Services, and the National Science Foundation do today. There could be equivalents at a state level, as there are today for some of these agencies. Such a federal body would address the maintenance of high-quality news and information, documentary resources, and historical record. It would invest in the maintenance and accessibility of the content pools that have already been created and that will grow with public participation. It would be structured to fund either commercial or noncommercial entities, so long as they made or enabled the making of public media. Alternatively, one might assign existing cultural and research support agencies responsibility for public media support.

Coordination that builds capacity for participation in public media 2.0 will pose a new challenge—distinct from the work of legacy media organizations, and untested as yet in the digital era. Functions of a coordinating body would include:

• providing an accessible, stable, and reliable platform for public interaction

• providing a toolset for participation in public media

• setting standards and metrics to assess public engagement

• developing a recommendation engine to identify and point to high-quality media

• committing staff at local and national levels primarily to building public engagement with media and to partnerships to make it happen

• tracking emerging technologies and platforms to assess and secure their potential for public media 2.0

The resulting platform would not be the only way or place for public media 2.0 to happen, but it would be a default location for engagement. It would not be the source of public media content, though its recommendations might be critical legitimation for such content. Rather, its staff would be charged first and foremost with promoting public life through media.

Who would do that? One might create such a coordinating body from whole cloth. It is also possible to imagine the linked organizations that comprise the public broadcasting system—with their federal public service mandate, local stations, and national programming outlets—playing such a role. There are, after all, public broadcasting stations, which could be local hubs of a national network, in nearly every metropolitan area in the United States, and there is a national body to manage federal dollars, the Corporation for Public Broadcasting. Public broadcasting, including CPB as a private nonprofit, is properly distanced from government to allow for free speech among public media 2.0 participants. Certainly no corporate entity appears a candidate to assume a national coordinating function, and emerging Internet sites have not yet garnered broad trust.

|

Public broadcasters face significant challenges to joint action. Well-known and profound structural problems, rooted in public broadcasting’s decentralized structure, the mixture of content production with distribution functions, and its multiple-source funding,39 impede collective action. So does a problem with vision. Public broadcasters have struggled with a transition to digital opportunities. The 2005 Digital Future Initiative report identified four categories in which public broadcasting could be useful going forward: lifelong education, local engagement, public health, and emergency preparedness. This was a list, albeit a good one, but not a mission. The mission of public media 2.0 is to enable publics with media to recognize and understand the problems they share, to know each other, and to act. Recent responses by NPR40and public broadcasting stations41 to the foreclosure crisis and economic bailout are small hints of the shift in focus required for public media 2.0. Public broadcasters might well identify roles for themselves both in content provision and in coordination. Such an approach would require restructuring and separating out content provision from coordination functions. It would need incentives from the federal government and a clear mandate to the Corporation for Public Broadcasting to execute the change. But it would also reclaim a multibillion dollar public investment in public media and avoid the challenge of creating a new structure that would have some overlapping functions. |

Public policy will turn experiment into habit. |

If the public gets a chance to build public media 2.0, it will not be merely because of structures such as a coordinating body and content funding. Government policies vital to building participatory capacity must be enacted at the infrastructure level. For instance, broadband needs to be accessible across economic divides and available to public media on equal terms with other, more commercial, media for a vigorous, expandable digital network of communication to thrive. Policymakers should mandate that network developers use universal design principles, so that people of all levels of enablement can access communication and media for public life. Users need privacy policies that safeguard their identities as they move across the digital landscape.

Government policies can also support the production of public media indirectly, with approaches that have been used successfully in the past. For instance, tax benefits could accrue not only to nonprofits but to any commercial entity offering pro bono services or creating public media. Government-funded media makers could be encouraged to use open source tools and platforms in order to spur innovation and resource sharing. Legislation could address copyright-driven obstacles to public media creation. And of course, support for life-long education will enhance the chances that every person can make media that can help make public life.

In short, there are big questions about how to develop public policies to support public media 2.0, but they are important to engage, because public policy will be crucial in turning isolated experimentation into pervasive public habit.

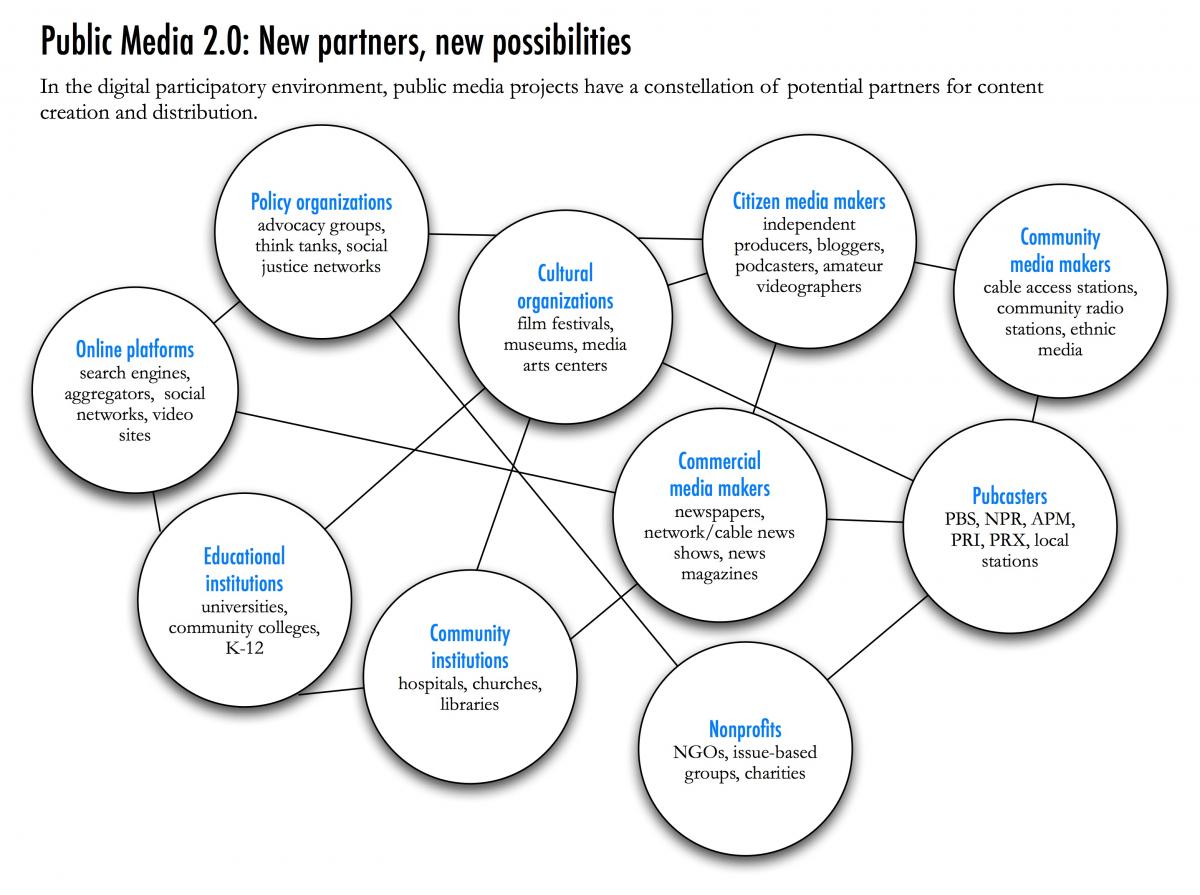

Partnership

Partnerships will permit public media 2.0 to happen across the social media landscape, building projects around the five C ’s of choice, conversation, curation, creation, and collaboration. While commercial media makers use cross-platform and cross-organizational strategies to produce “synergies” that strengthen their brands and draw in more customers, public media makers can use them to increase awareness around issues, drive support to the public sector, and build and mobilize publics. Some partners will be individuals, but many will be institutions.

Potential institutional partners for public media 2.0 today include legacy public media, independent makers, community media outlets, digital companies, social entrepreneurs, and nonprofit institutions.

The assets of legacy public media—public broadcasters, prestige newspapers and magazines, respected broadcast news programs, and tried-and-true independent media outlets—include public trust, connections to existing communities, deep archives (even if sometimes fraught with ownership issues), and long-time relationships with funders and advertisers.

|

Community media makers—such as low-power FM and cable access stations, independent TV and radio stations, and youth media outlets—are often already primed to train and support those interested in making their own media. Digital companies—including social media platforms, search engines, hardware and software developers, and Web 2.0 startups—offer businesses based from the ground up on participation and an understanding of the importance of noncommercial content and projects in building an attractive commercial model. Institutions in the nonprofit sector that are strong partners for public media projects include universities, museums, and libraries, as well as issue-focused educational and social organizations. Their assets include archives and databases, issue expertise, legitimacy, and trusted brands. Universities and federal research agencies are already wired to next-generation fiber optic networks, which could be used, as the National Public Lightpath project envisions, to create a cooperative public media broadband infrastructure.42 Nonprofits can also serve as hosts for long-term education and advocacy campaigns that media makers may spur but are not prepared to sustain. |

Partnerships reveal the hybrid nature of public media 2.0. |

Social entrepreneurs, both in the foundation world and in corporate environments, are seeking partners who can deliver a “double bottom line” of social good and profit. Their projects can serve as points of connection for actors and outlets from different media sectors. (See “Social Entrepreneurs and Public Media 2.0” p. 27)

Collaborative experiments so far bode well. Educational and advocacy organizations are finding points of contact with public media makers around issues,43 while noncommercial and commercial outlets are developing partnerships that exchange prestige for reach.44

Community projects, such as Philadelphia’s Plan Philly site (http://www.planphilly.com), bring journalists, educators, and citizens together to address local issues. Citizen journalism projects, such as Vocalo (http://vocalo.org/), Talking Points Memo (http://www.talkingpointsmemo.com) and Open Salon (http://open.salon.com), are collaborating with audiences to create and select content and to investigate breaking stories. These new partnerships demonstrate the hybrid nature of public media 2.0—commercial- noncommercial, pro-am, media-nonmedia institutions.

An incubator for hybrid projects, the Bay Area Video Coalition’s Producer’s Institute matches up independent and public media makers with commercial Web tools to produce working digital engagement prototypes. The sessions equip producers with powerful new technologies, while providing industry leaders with compelling examples of how their products can enable public participation. One such project is iWitness (http://www.pbs.org/frontlineworld/stories/iwitness/), hosted online by the PBS series Frontline/World. Producers worked with BAVC trainers to combine webcams and the Internet telephone service Skype to build a customized tool that enables citizens and experts on the ground to report on breaking news. The project launched with a story about riots in Johannesburg and was so popular it jumped immediately to the PBS home page.

Twitter Vote Report (http://blog.twittervotereport.com), launched just three weeks before the 2008 presidential election, suggests how quickly joint public media 2.0 projects can be organized. Both NPR and PBS signed on as partners to the project, designed to leverage the microblogging site Twitter to allow voters to report live on their experiences at the polls. After the idea was floated on the Personal Democracy Forum blog, volunteers stepped up to strategize Twitter tags, build related iPhone applications and online visualizations, create a public site for the project, and spread the word to media, bloggers, and get-out-the-vote organizations. A range of nonprofit and technology partners signed on, and more than 8,000 users reported in, creating a real-time record of voting issues around the country.

SOCIAL ENTREPRENEURS AND PUBLIC MEDIA 2.0

Can business and public life work together? That’s the hope of some social entrepreneurs who target media, blending economic, social, and environmental values.45

Omidyar Network

In addition to providing grants, the Omidyar Network reframes philanthropy as a low-interest investment. Pierre Omidyar, the founder of eBay, and his wife, Pam, for established the Omidyar Network in 2004. They have worked with their partners to create opportunities that enable people to “improve their lives and make powerful contributions to their communities.” These efforts are organized around two investment initiatives: Access to Capital, and Media, Markets, and Transparency. The Omidyar Network’s portfolio of past and current partners/ grantees includes One World, WITNESS, Green Media Toolshed, the Sunlight Foundation, and SourceForge.Net (http://www.omidyar.net/portfolio.php/).Participant Media

Participant Media, founded by Jeff Skoll, the first employee of eBay, asserts that “a good story well told can truly make a difference in how one sees the world.” Participant has produced dozens of dramatic features over the past few years, including Good Night and Good Luck, as well as a number of leading documentaries, including the Academy Award–winning Inconvenient Truth. Films are designed with social action campaigns in mind, and investment is allocated for engagement projects. Participant teams up with social sector organizations, nonprofits, and corporations that are committed to creating open platforms for discussion and education and that can, with Participant, offer specific ways for audience members to get involved. The company has also launched a new social action network entitled Take Part (http://www.takepart.com/).Sundance Channel

The Sundance Channel is a for-profit company with a strong public purpose to showcase independent work. Founded by Robert Redford and his colleagues at the Sundance Institute, it is one of cable television’s most ambitious venues in exploring public media 2.0. The Green (http://www.sundancechannel.com/thegreen/) is television’s first regularly scheduled programming destination dedicated entirely to the environment, with major series, such as Big Ideas for a Small Planet. Its extensive Web component features a social networking site, Eco-mmunity (http://www.sundancechannel.com/ecommunity/).Channel Four Television’s New Media

Commissioning Department

The U.K.’s Channel Four Television, a commercial public channel committed to showcasing independent audio-visual production, has pioneered interactive experiments. Big Art Mob (http://www.bigartmob.com/), a mobile phone blog, encourages audiences to track down and document interesting examples of British public art. 4Talent (http://www.channel4.com/4talent/ national/newmedia/) encourages user-generated approaches to creating new programming ideas, formats, and content. The Four Innovation for the Public (4IP) fund, (http://www.4ip.org.uk/) is a collaboration between the channel and U.K. development and media agencies, with anaim to decentralize how public media is produced and delivered.

STANDARDS AND PRACTICES

In the one-to-many environment, public media organizations served as gatekeepers and standards-bearers, enforcing norms and selecting content and makers that matched their missions. In the networked, collaborative, many-to-many media environment, standards and metrics will be universally applicable tools for public media makers and providers.

Mission

Public media 2.0 will be built around mission, most fundamentally the ability to support the formation of publics—that is, to link us to deep wells of reliable information and powerful stories, to bring contested perspectives into constructive dialogue, to offer access and space for minority voices, and to build both online and offline communities. How can we recognize public media 2.0 projects in the networked information environment? Like any good participatory media project, they should be open (multidirectional, dynamic, networked), iterative (with good feedback loops), accessible (easy to use without high-end equipment or skills), and egalitarian (letting all participants see each other as significant contributors). But to be public media, they should have at their core the mission to mobilize publics with whatever media are on offer. They should enable participants to shape an informed judgment on which they can act.

Outcomes

|

In a world where public media 2.0 is about doing rather than being, measuring success becomes critical. How can you measure the enabling of public life? How do we know when a public has formed? New impact metrics might include: facts learned; conversations launched; mental frameworks changed; events held; policies proposed, endorsed, or challenged; videos shared; memes spawned; students involved; skills acquired; and submissions posted. Public media benchmarks should also take into account the composition of participants, given the social, economic, political, and ethnic divides of the society. Do media projects create a sense of trust and buy-in, making audiences feel as though they have a voice and can make a difference? |

Public media 2.0 is about doing, not being. |

Developing methods for measuring such impacts is a fast-evolving field. Compelling new online tools, such as network mapping47 and data visualization,48 make it possible to explore the dynamics of media dissemination in unprecedented richness and detail. Impact measurements from the community media49 and media development50 fields also offer some clues.

Failed experiments have as much to tell us as successes. For instance, the Why Democracy? project, a collection of documentaries aired in the same month around the globe and linked to public discussion, succeeded in winning broadcast airings but failed at launching global conversations.51 Information sharing from the organization’s leaders helped future project designers.

CONCLUSION

In this rare moment of transition, different stakeholders have different opportunities:

Public media institutions have a chance to play a leadership role in several ways. They can elevate and act upon internal discussions about how to develop sturdy digital platforms for collaboration, engagement, and future innovation. They can jointly build or endorse a national coordinating body that will support digital content and interaction. They can individually convene and coordinate public media 2.0 experiments. Such experiments, properly publicized and documented (including their weaknesses), are the seed from which the public media 2.0 environment will grow. All such efforts need to build from a mandate to mobilize publics and incorporate participatory platforms and engagement campaigns. Public media institutions need to reach far beyond the traditional demographics of their mass media audiences and to cross cultural, social, economic, ethnic, and political divides. They need to serve as a beacon in their own communities, daily demonstrating the vitality and importance of public media 2.0.

Public media makers have a chance to develop and publicize emerging models of production that depend on the people formerly known as the audience for funding, distribution, publicity, and the actions that demonstrate that a project has succeeded in engaging publics. They can work with—as well as beyond—legacy media institutions, to bring standards and mission-driven values long typical of the journalistic and independent creator communities to the challenge of pioneering public media 2.0.

Policymakers can position public media 2.0 as a core function of a vital democratic public and support it at national, regional, and local levels. They can call upon existing public broadcasting institutions to pioneer participatory public media projects. They can support infrastructure policy that enhances broad public participation in public media. They can support programs that enable all members of the society to be media literate and to participate in public media 2.0. They can use public media 2.0 principles in their own communication with the public.

Funders can put the mission to build dynamic, engaged publics at the heart of their investments in media projects. They can require grantees to demonstrate that goal for any continued institutional funding. They can support the development of standards and practices and of tools that enable ranking, vetting, and valuing of content. They can develop measures to assess the degree to which a funded effort is expanding and equalizing participation in public life.

All these efforts will create, not only new tools, new habits, new platforms for action, but also greater public understanding of why public media 2.0 needs to be built, nurtured, funded, and sustained by the American people themselves. The most basic challenge for public media 2.0 is to generate political capital for it. People need to make demands for public media 2.0 of their elected officials, their regulators, their communications service providers, and their media entities.

That challenge must begin, as always, in conversations among engaged publics. Stakeholders, whether they are incumbents, innovators, or both, need to begin that conversation. They are the core public for public media 2.0 today.

Those stakeholders need to host these conversations within the networks of attention and concern that they command, in order to mobilize them to demand a vital public media 2.0. Publics can act powerfully and flexibly; they are grown and nurtured within rich communications environments. These environments exist today and can become more effective as they develop links across sectors and as they develop awareness, investment, and a shared vision with wider, engaged publics.

REFERENCES

10 Questions Presidential Forum. 2008, from www.10question.com

Abrash, B. (2007). The View from the Top: P.O.V. leaders on the struggle to create truly public media. Washington, DC: Center for Social Media.

Alexa: The Web Information Company. (2008). Traffic History Graph for ourmedia. org. Retrieved October, 2008, from http://www.alexa.com/data/details/traffic_details/ourmedia.org

America for Obama. (2008). Keating Economics: John McCain and the making of a financial crisis.2008, from http://www.keatingeconomics.com/

American Civil Liberties Union and the ACLU Foundation. Freedom Files Season Two. 2008, retrieved from http://aclu.tv/

Aufderheide, P., & J. Clark (2008). The Future of Public Media FAQ. Retrieved April 2008, from http://www.centerforsocialmedia.org/future-public-media/documents/articles/frequently-asked-questions-public-media

Benkler, Y. (2008). The Wealth of Networks. Retrieved from http://cyber.law.harvard.edu/wealth_of_networks/Main_Page

Brotherton, D., & C. Scheider (September 2008). Come On In. The Water’s Fine: An exploration of Web 2.0 technology and its emerging impact on foundation communications: Brotherton Strategies.

Calabrese, M., & C. Carter (2005). Digital Future Initiative Final Report: Challenges and opportunities for public service media in the digital age: New American Foundation.

Carr, D., & B. Stelter (2008). Campaigns in a Web 2.0 world [Electronic Version]. The New York Times. Retrieved November 2, 2008, from http://www.nytimes.com/2008/11/03/business/media/03media.html?_r=1&pagewanted=1&th& emc=th&oref=slogin

Chester, J. (2007). Digital Destiny: New media and the future of democracy: The New Press.

Clark, J. (2008). Mapping Public Media: Inside and out. Washington, DC: Center for Social Media.

Cole, J. (2008). Informed Comment: Thoughts on the middle east, history, and religion. Ann Arbor, Michigan.

Daou, P. (2008). The revolution of the online commentariat. The Huffington Post. Retrieved from http://www.huffingtonpost.com/peter-daou/the-revolution-of-the-onl_b_149253.html.

Davis, M. Semantic Wave 2008 Report: Industry roadmap to Web 3.0 and multibillion dollar market opportunties. Retrived from http://www.project10x.com/about.php

Emerson, J., & Bonini, S. (2003). The Blended Value Map: Tracking the interests and opportunities of economic, social and environmental value creation: Blended Value.

Feministing.com. (2008). Retrieved from http://www.feministing.com/about.html

Fine, A. (2006). Momentum: Igniting social change in the connected age. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.patrick, G. (2008). Field Report: “Why Democra” Washington, DC: The Center for Social Media.

Frontline World: Stories from a Small Planet. (2008). South Africa: “Go Away and Fight Mugabe!” Retrieved from http://www.pbs.org/frontlineworld/stories/iwitness/

Glaser, M. (2008). Political fact-check sites proliferate, but can they break through the muck? MEDIASHIFT: Your Guide to the Digital Revolution Retrieved from http://www.pbs.org/mediashift/2008/09/political-fact-check-sites-proliferate-but-can-they-break-through-the-muck268.html

Glaser, M. (2008). Gannett pushes for more tech hires, data centers, niche sites, MEDIASHIFT: Your Guide to the Digital Revolution Retrieved from http://www.pbs.org/mediashift/2008/10/gannett-pushes-for-more-tech-hires-data-centers-niche-sites-284.html

Goodman, E.P. (2009). Public service media 2.0. And Communications for All: A Policy Agenda for a New Administration, (Amit M. Schjecter, ed.) Lexington Books.

Haenel, B. (2008). PubForge: open source solutions for public broadcasters. Retrieved from http://pubforge.org

Harvey, M. (2008). Sarah Palin Wikipedia entry gets glowing make-over from mysterious user Young Trigg [Electronic Version]. Times Online. Retrieved from http://www.timesonline.co.uk/tol/news/world/us_and_americas/us_elections/article4653971.ece

Hume, E. (2008). Defining civic media at MIT [Electronic Version]. Idea Lab: Reinventing Community News for the Digital Age. Retrieved from http://www.pbs.org/idealab/2008/07/home-brew-1.html

June-Friesen, K. (2008). Observing subprime ‘tsunami,’ CPB commissions a response [Electronic Version]. Current, from http://www.current.org/outreach/outreach0812mortgage.shtml

Kaplan, D. E. (2008). Empowering Independent Media: U.S. efforts to foster free and independent news around the world. Washington, DC: Center for International Media Assistance.

Krebs, B. (2008). Wikipedia edits forecast Vice Presidential picks [Electronic Version]. washingtonpost.com, from http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2008/08/29/AR2008082902691.html

Lessig, L. (2008). Remix: Making art and commerce thrive in the hybrid economy. Penguin Group. 35 Public Media 2.0: dynaMic, engaged Publics

Linkfluence. (2008). Presidential Watch 08. 2008, from http://presidentialwatch08.com/index.php/map/

Lucas, M. (2006). Creating Multiple Global Publics: How Global Voices engages journalists and bloggers around the world. Washington, DC: Center for Social Media.

Marchetti, S. (2008). Your brand and the blogosphere: 5 statistics you should know, 360 Digital Influence. Washington: Ogilvy Public Relations Worldwide.

Mattson, E. The game has changed: college admissions outpaced corporations in embracing social media, Higher Ed. Blogs. North Dartmouth: University of Massachusetts Dartmouth.

Miel, P., and R. Faris (2008). News and Information as Digital Media Come of Age. Media Re:public. Cambridge, Massachusetts, Berkman Center for Internet and Society at Harvard University: 1 – 11.

Olson, M. (2008). Public media serves up election widgets for bloggers, Inside NPR.org. Washington, DC: NPR.org.

Palfrey, J., & Gasser, U. (2008). Born Digital : understanding the first generation of digital natives.New York: Basic Books.

Paterson, R. (2008). Social Media must be able to do things and get measured— KETC and the Mortgage Crisis [Electronic Version]. FASTforward, from http://www.fastforwardblog.com/2008/10/21/social-media-must-be-able-to-do-things-and-get-measured-ketc-and-the-mortgage-crisi/

Pew Internet & American Life Project. (2008). Teens, Video Games, and Civics: Teens’ gaming experiences are diverse and include significant social interaction and civic engagement

Pew Research Center. (2008). Key News Audiences Now Blend Online and Traditional Sources. Washington: Pew Research Center for People and the Press.

Sasaki, D. (2008). An Introductory Guide to Global Citizen Media. from http://rising.globalvoicesonline.org/blog/2008/01/16/a-introductory-guide-to-global-citizen-media/

Schuler, K. (2008). Field Report: OneWorld’s Virtual Bali. Future of Public Media. Washington, DC, Center for Social Media.

Seward, Z. M. (2008). ProPublica and NYT seek $1M to put everyone’s documents online, Nieman Journalism Lab (Vol. 2008). Cambridge, Massachusetts: Nieman Foundation at Harvard University.

Shedden, D. (2008). Media Ethics Bibliography. In J. Moos (Ed.), Poynter Online (September 9, 2008 ed., Vol. 2008). St. Petersburg, Florida: The Poyter Institute.

Shirky, C. (2008). Here Comes Everybody: The power of organizing without organizations. New York: The Penguin Press.

Sifry, M. L. (2008). Bailout datatorial: follow the money from Wall St. to DC, 1990-present, Personal Democracy Forum: techPresident. Retrieved from http://www.personaldemocracy.com/blog/entry/2098/bailout_datatorial_follow_the_money_from_wall_st_to_dc_1990_present

Singel, R.. With flickr layoffs, whither ‘the commons’? Wired Blog Network. Retrieved December 2008 from http://blog.wired.com/business/2008/12/with-layoffs-wh.html

Stickney, D. (2008). Charticle fever [Electronic Version]. American Journalism Review. Retrieved October/November 2008, from http://www.ajr.org/Article.asp?id=4608

Sullivan, F., & Kidd, D. (2007). Impact on Our Own Terms: Center for International Media Action.

Sunstein, C. R. (2007). Republic.com 2.0. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Take Part Media. (2006). Take Action. 2008, from http://www.climatecrisis.net/takeaction/

The Cincinnati Enquirer. 2008, from http://data.cincinnati.com/navigator/

Twin Cities Public Television. (2007). Twin Cities Public Television Show Descriptions. 2008, from

http://www.washingtonian.com/blogarticles/people/capitalcomment/10108.html

Vaidhyanathan, S. The Googlization of Everything. 2008, from http://googlizationofeverything.com/

Vargas, J. A. (2008). Palin Online: Staggering Numbers [Electronic Version]. The Clickocracy, from http://voices.washingtonpost.com/the-trail/2008/09/17/palin_online_staggering_number.html?hpid=topnews

Verclas, K. (2008). A Mobile Voice: The use of mobile phones in citizen media: MobileActive.org.

Wikimedia Foundation. (2008). Sarah Palin [Electronic Version]. Wikipedia: The free encyclopedia, from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sarah_Palin

Wikipedia: The Free Encyclopedia. (2008). Wikipedia: Neutral point of view [Electronic Version]. from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wikipedia:Neutral_point_of_view

WITNESS. Video in ACTION: WITNESS Case Studies. 2008, from http://www.witness.org/index.php?Itemid=60&id=24&option=com_content&task=blogcategory

Wittke, K. (2007). The War Tapes Puts a Face on War. Washington, DC: Center for Social Media.

Wu, J. (2008). All About iPhone [Electronic Version]. Retrieved October 2008, from http://www.comscore.com/iphone/

YouTube. (2008). Respect the YouTube community. 2008, from http://www.youtube.com/t/community_guidelines

Zittrain, J. (2008). The Future of the Internet and How to Stop It. London: Yale University Press.

END NOTES

1 Thanks to Diane Mermigas of MediaPost for helping us to develop an earlier version of this graphic for the 2008 Beyond Broadcast conference.

2 In The Berkman Center’s Media Re:public project, News and Information as Digital Media Come of Age. (2008)., Persephone Miel and Robert Feris argue that the decline of the advertising-based business model is leading the disruption in legacy journalism organizations and that support and collaboration will be needed to shore up the core civic functions of journalism. They also recommend investment in intermediaries that build bridges between high-quality information and publics.

3 A December 2008 survey from the Pew Research Center for the People and the Press reveals that, for the first time, respondents say that while television is still their main source for national and international news (70%), the Internet (40%) now surpasses newspapers (35%). For audience members under 30, the Internet and television are neck-and-neck as news sources.

4 As Lawrence Lessig writes in Remix: Making Art and Commerce Thrive in the Hybrid Economy: “Commercial economies build value with money at their core. Sharing economies build value, ignoring money. Both are critical to life online and offline. Both will flourish more as Internet technology develops. But between these two economies, there is an increasingly important third economy: one that builds upon both the sharing and commercial economies, one that adds value to each. This third type—the hybrid—will dominate the architecture for commerce on the Web.”

5 Internet strategist Peter Daou notes in an essay for the Berkman Center’s Publius Project, “The context, perception, and course of events is fundamentally changed by the collective behavior of the Internet’s innumerable opinion-makers. Every piece of news and information is instantly processed by the combined brain power of millions, events are interpreted in new and unpredictable ways, observations transformed into beliefs, thoughts into reality. Ideas and opinions flow from the ground up, insights and inferences, speculation and extrapolation are put forth, then looped and re-looped on a previously unimaginable scale, conventional wisdom created in hours and minutes. This wasn’t the case during the last presidential election—the venues and the voices populating them hadn’t reached critical mass. They have now.”

6 The Semantic Wave 2008 Report, published by consulting firm Project 10X in September 2008, describes several of the coming technologies: “A key trend in Web 3.0 is toward collective knowledge systems where users collaborate to add content, semantics, models and behaviors, and where systems learn and get better with use. Key features of Web 3.0 social computing environments include (a) user generated content; (b) human-machine synergy; (c) increasing returns with scale; and (d) emergent knowledge.”

7 Clay Shirky and Allison Fine have documented how individuals and groups have leveraged technologies like e-mail, low-cost video, mobile communication, social networks, and blogs for advocacy around issues large and small.

8 See this June 2008 map of the political blogosphere for an example of the relationship between links across blogs and news sites and the influence they wield: http://presidentialwatch08.com/index.php/map/

9 See the Spot.us project (http://www.spot.us/) for one example of community-funded reporting.

10 A widget is a small, self-contained piece of code that performs a particular task. 11 A December 2008 report by the Pew Internet and American Life Project predicts that mobile devices will be the primary means of connecting to the Internet by 2020, a trend sure to drive the expansion of place- based media.

12 A September 2008 report from the Pew Internet and American Life Project notes that 97% of teens ages 12–17 play some kind of electronic game.

13 Layoffs at Flickr demonstrate the dangers of depending on commercial platforms for maintaining public media 2.0 projects. As Wired’s Epicenter blog reported on December 30, the photo-hosting site laid off George Oates, the manager of The Commons, a project that allowed users to browse, tag, and analyze tens of thousands of copyright-free images posted by 17 cultural institutions, including the Library of Congress and the New York Public Library. Active users quickly rallied to save the project, but observers suggest that the host institutions should host backup collections. See “With Flickr layoffs, whither ‘the commons’?” (2008). for more details.

14 As keynote speaker Larry Irving noted at the 2008 Beyond Broadcast conference, “If you look at the skewing of public broadcasting, the median age of public broadcasting viewers is 46 years old. The median age of this country is 36 years old; the median age of Latinos in this country is 24 years old. We are going to grow by 130 million people between 1995 and 2050, and 90 percent of that growth will be people of color.”

15 See the Center for Social Media field report on the Virtual Bali project for more details: Field Report: OneWorld’s Virtual Bali. (2008).

16 For a detailed discussion of the concept of participatory public media, see the Center for Social Media’s Future of Public Media FAQ.

17 Check the Media Shift Idea Lab (http://www.pbs.org/idealab/) for running blogs by Knight News Challenge grantees exploring new concepts in community news.

18 “Public media serves up election widgets for bloggers,” Inside NPR.org, http://www.npr.org/blogs/inside/2008/08/public_media_serves_up_electio.html

19 See An Introductory Guide to Global Citizen Media (2008) for many examples.