December 2003

Report by:

Pat Aufderheide, Co-Director, Center for Media & Social Impact, American University

With substantial funding from:

The Ford Foundation

And additional help from:

Phoebe Haas Charitable Trust

American University

Grantmakers in Film and Electronic Media

This report provides an overview of U.S.1 social documentary production and use. Social documentaries often openly address power relations in society, with the goal of making citizens and activists aware and motivated to act for social justice, equality and democracy. Documentaries expressly designed to play this role are the subject of this report. They are live links in the communications networks that create new possibilities for democracy. Social documentary production and use are described in four, sometimes overlapping areas: professional independent production aimed at television; alternative production; community media; and nonprofit production.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The conclusions in this report depend on expertise I have garnered as a cultural journalist, film critic, curator and academic. During my sabbatical year 2002-2003, I was able to conduct an extensive literature review, to supervise a scan of graduate curricula in film production programs, and to conduct three focus groups on the subject of curriculum for social documentary. I was also able to participate in events (see sidebar) and to meet with a wide array of people who enriched this study.

I further benefited from collegial exchange with the ad hoc network of scholars who also received Ford grants in the same time period, and from interviews with many people at events and also via phone and Internet. Among the people who provided me with valuable interview material are members of the Center’s advisory board, as well as Larry Daressa of California Newsreel, Elizabeth Fox of AID, Chris Hahn of Children’s Express, Bill Henley of Twin Cities Public TV, Sheri Herndon of Indymedia, Steve Mendelsohn and Tracy Holder of Manhattan Neighborhood Network, Rhea Mokund, assistant director of Listen Up!, Peggy Parsons at the National Gallery of Art, Bunnie Reidel, Executive Director of the Alliance for Community Media, Nan Rubin, Ellen Schneider, executive director of ActiveVoice, Nina Shapiro-Perl of Service Employees International Union, John Schwartz of Free Speech TV , John Stout of Free Speech TV , Elizabeth Weatherford, National Museum of the American Indian, Robert West of Working Films, Debra Zimmerman, Executive Director of Women Make Movies. Focus group members included Randall Blair, Michal Carr, Ginnie Durrin, Elizabeth Fox, Phyllis Geller, Charlene Gilbert, Judith Hallet, Tony Hidenrick, Jennifer Lawson, Joy Moore, Dana Sheets, Robin Smith, Fred Tutman, Dan Sonnett, Virginia Williams, and Steve York. Advisors on policy included Gigi Bradford, Cindy Cohn, Shari Kizirian, Chris Murray, Andy Schwartzman, Gigi Sohn, Jonathan Tasini, and Woodward Wickham. Patrick Wickham of the Independent Television Service co-designed charts showing linkages between production, distribution and policy. The manuscript benefited as well from the comments of Barbara Abrash, Nicole Betancourt, Helen De Michiel, Ginnie Durrin, Thomas Harding, Fred Johnson, Alyce Myatt, jesikah maria ross, Jeff Spitz, Woodward Wickham, and Patricia Zimmerman. Many more people talked with me informally, and I am grateful for their generosity, a hallmark of this arena of activity.

I drew extensively upon my work since 1996 as curator of the Council on Foundations Film and Video festival, for examples and information, and am deeply grateful to Evelyn Gibson at the Council for an extended education in this creative field. The Council has established a website, fundfilm.org, which provides information on many films referred to here, and many more as well.

A grant from the Ford Foundation made this research possible and sustained it over the course of the sabbatical year. A grant from the Phoebe Haas Charitable Trust, which supported work at the Center for Social Media, permitted me to extend my sabbatical. The University Senate at American University provided grants for curriculum development and for travel. Grantmakers in Film and Electronic Media provided funds for dissemination of the report. The encouragement of Dean Larry Kirkman at American University was essential to this work. Jana Germano, Shari Kizirian, Paula Manley, Felicia Sullivan, and Agnes Varnum assisted in research. Jana Germano brought both great creativity and patience to the design of the report.

INTRODUCTION

This report provides an overview of U.S.1 social documentary production and use. Social documentaries often openly address power relations in society, with the goal of making citizens and activists aware and motivated to act for social justice, equality and democracy. Documentaries expressly designed to play this role are the subject of this report. They are live links in the communications networks that create new possibilities for democracy. Social documentary production and use are described in four, sometimes overlapping areas: professional independent production aimed at television; alternative production; community media; and nonprofit production.

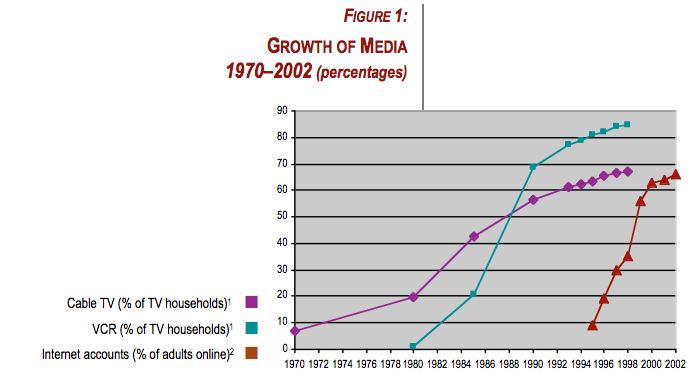

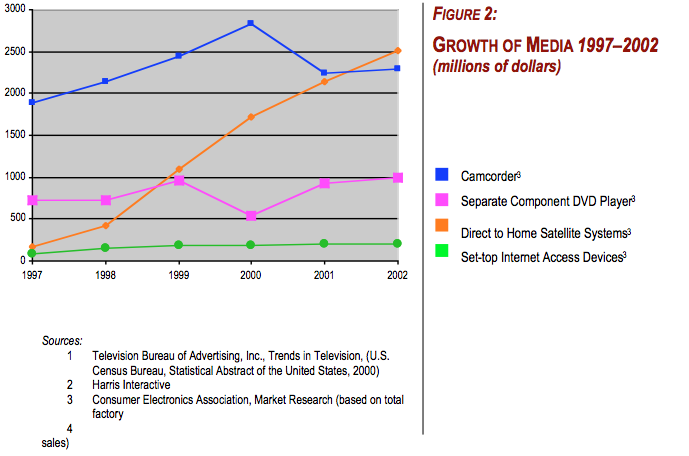

Camcorders, VCRs, DVDs have vastly increased the opportunity to make and see social documentaries, and the Internet and World Wide Web have only speeded the process.

So it has never been easier or cheaper to make a social documentary than today. Many a film professional will grumble, though, that it’s still pretty hard to make a watchable one. No matter how cheap it gets to capture images and edit them on your own computer, a social documentary is an artform, and it requires the powerful storytelling skills that are at the base of that artform (Bernard, 2003). It also requires the expert skills of craftspeople ranging from camera to lighting to digital effects to editing. Their jobs may be facilitated by technology, but the technology can’t teach them their craft.

It is also hard to match viewers with the documentary, and so far new technologies have not solved that problem either. (You can easily load a film onto an Internet site; the wit comes in figuring out how to make people want to download it.) When you see a documentary that addresses power relations, you are usually looking at work that has passed over big hurdles. It has not only won resources to make a well-crafted work. It has also benefited from a successful marketing and promotion strategy, and distributors or programmers have usually greenlighted it to the screen you watch it on. The work you see was probably enabled, directly or indirectly, by government policies, whether those that established public TV or arts and humanities agencies or the Internet itself. Finally, you are looking at work usually fuelled by the belief that participatory democracy needs diverse expression.

Background

Today’s documentary practices emerge both from technological developments and from powerful social trends.

The civil rights movements, starting with the battle for civil rights for African-Americans and growing with feminist, ethnic rights and gender rights movements, spurred many people to express their views, to create new institutions, and to seek out support for expanded notions of citizenship and rights. The expansion of nonprofit organizations, including those that represent rights movements, created institutional vehicles to channel that energy. Public and foundation investment in culture and in mass media created new resources for aspiring makers and institutions that supported them.

In the 1960s, dissident filmmakers working in the social documentary tradition began using film and video to challenge authorities ranging from the U.S. Pentagon (as the collectively made, anti-Vietnam War film Winter Soldier did) to union-busting corporations (as Barbara Kopple did with Harlan County, USA). Filmmakers formed groups to create works by and with citizens and community members. Kartemquin Films, which went on to make such major theatrical releases as Hoop Dreams and Stevie, worked during the later ’60s and ’70s as a collective that documented and worked with working people. Kartemquin’s earliest work featured anti-war students, members of the Chicago youth activist group Rising Up Angry, and others.

These filmmakers established the image of the independent filmmaker as society’s conscience, perhaps unconsciously echoing the English documentary producer John Grierson’s goal of creating a “documentary conscience.” They founded organizations such as Association for Independent Video and Filmmakers and the National Alliance for Media Arts and Culture to defend their interests, and they formed distributors such as the cooperative New Day Films. They organized for and won greater access to public television, and created, in tandem with civil rights organizations, groups defending interests of minority filmmakers. Closely related to this aggressively independent filmmaking stance was that of the entrepreneurial investigative journalist, whose work would emerge on public affairs programs on television; Jon Alpert, Bill Moyers, and Peter Davis were among those who became independent broadcast journalistic voices (Barnouw, 1993). Major private funders supported this work over time. For instance, the Ford Foundation’s early backing for public TV also nurtured social documentarians; the Rockefeller Foundation Media Arts Fellowships, which began in 1988, encouraged many socially-engaged filmmakers striving for artistic innovation (Rockefeller, 2002; Zimmermann, 2000; Zimmermann & Bradley, 1998).

Some makers saw themselves liberated from a professional tradition, and used media as part of an oppositional or alternative cultural stance in an aggressively commercial culture. Political newsreels such as those produced by Newsreel, “guerrilla” video, pirate radio, TV programming initiatives such as Paper Tiger and Deep Dish, and some young people’s media all participated in this “alternative” or “radical” media phenomenon, which created vehicles and venues outside commercial media (Kester, 1998; Halleck, 2002; Boyle, 1997).

Others began making and using video as part of strategic campaigns, making media part of their toolkits. Environmental organizations such as Greenpeace and Earth First documented their own actions both to give to mainstream media for coverage, and to use in organizing and recruiting (Harding, 2001; Hirsch, 2000).

In the late ’60s and early ’70s, social activists began to see media as enabling and enabled by community development. Media arts centers, some sponsored by Great Society-initiative funds, offered new voices the chance to express themselves, and to explain their cultures to others. The now-widespread phenomenon of cable access channels – cable TV channels dedicated to governmental, educational and public programming – resulted from grassroots community organizing to demand such channels in the franchise negotiating process. Cable access activists commonly saw themselves creating not more TV programming but new resources for community self-knowledge and growth. As computing became accessible to consumers in the 1980s, the same logic drove activists to form community technology centers related to social service agencies, nonprofit organizations and as stand-alone projects. There, people could learn computing skills, connect to the Internet, and, increasingly, compose media. Foundation support for community media – notably, from the 1980s to the early 21st century at the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation – helped to sustain the work. So did public resources, such as cable franchise fees given under municipal contracts and state and federal economic development funds. (Sullivan, 2003)

Professionals often understand media as the lifeblood of an information society; activists see media as a voice of a movement or action; institutional organizers often see the mediamaking process as a means to individual and community development. These expectations can overlap, of course. Indie filmmakers want their films to reach out from broadcast to community activists, while nonprofits hope to get a TV window for their issue.

Success in the Public Sphere

We know very little about the success of such efforts, and estimates of long-term impact are speculative. Especially since social documentaries often depend on funding outside the usual profit streams, many funders are frustrated by the problems of measurement. Media expressions are, by their nature, a puzzle to evaluate for their consequences, much less any effectiveness at achieving an intended result. In commercial television, measures such as ratings and webhits ask a simple question: did this work reach viewers we consider valuable? Just finding them is enough for advertisers, who are convinced through experience that exposure leads for enough of them to action. Expensive and unreliable, these measures nonetheless are the shared data for one of the most important business sectors in the U.S.

Going beyond exposure, you confront the fact that our media habits are threads in our cultural tapestries, not stand-alone features; their impact on our beliefs and actions are sometimes impossible to separate from other parts of our experience. The social science pursuit of media social effects is hobbled by this reality. Laboratory conditions do not bear much similarity to peoples’ lived experience with media. Social scientists in this as in other arenas of social science depend on a combination of qualitative and quantitative approaches, to provide a range of techniques to address the same problem in the hopes that the limitations of each can be supplemented by others (Jensen 2002, Jensen 2002a).

Grounded, empirical studies of the creation and circulation of media are few, and they have typically not been executed on one-time events and certainly not on documentaries (Schrøder, 2002, 108). Textual analysis (a favorite of the literarily inclined), reception analysis (an approach congenial to the more sociologically inclined), and political economic analysis (political scientists and economists have been drawn to this approach) have all been employed to establish some basic generalizations about media social effects (Murdock, 2002). Even the 30-year, Congressionally-funded studies investigating relationships between violent television programming and children’s violent behavior resulted in only broad generalizations (Liebert & Sprafkin, 1988).

Cultural studies theorists, and some political economy analysts, have focused directly on the issue that makes many funders deeply uncomfortable: the relationship between media and power. Stuart Hall and other cultural studies theorists argue that media both are created in a world of meaning and also constitute that world of meaning (Hartley, 2002). Thus, they have conceived the challenge of understanding the role of media as that of communicating power – at the most basic and crucial level, the power to establish the nature of reality. Intervening in the media flow is always a way of disrupting the status quo. So if, as scholar James Carey (1989) has put it, “reality is a scarce resource,” every TV program and every DVD is part of the contest over it.

Philosophers have also engaged the question of media as a force in public, democratic culture. The very notion of the public has long kept scholars and politicians in contentious discussion. It is a highly elastic concept, and one more often invoked than defined, but it is worth looking at closely, when we think about media. What American philosopher John Dewey thought of when he thought of the public is helpful in seeing the link between media and democracy. Dewey described a public that creates itself – that comes into being as it acts as an independent social force (Dewey, 1927). It takes action on issues that affect everyone in the public, civic side of their lives. You know a public is real when people in a community are able to know about and act on problems created by some members of that community – be it a criminal, a polluting corporation, or an unresponsive government – that affect everyone in it.

This public is distinct from government, which can be a force acting against the public; or individuals, who can only act as individuals; or the mass of consumers that make up audiences or markets. The public is a concept, not an institution or a thing. A person in a democratic society is a member of a public as well as having other identities, but that person isn’t forced to segregate his or her concerns. One of the important nurturing institutions for the public is the non-governmental, voluntary association, whether a church or a human rights group or a civic association or a parents’ group.

This sense of the public resonates well with the notion of the public that the German philosopher Jürgen Habermas conveyed in his helpful phrase “the public sphere” (Habermas, 1989). Habermas noted the imperfect, unrepresentative but still vital role played by members of 18th century French salons in shaping a public that demanded universal human rights, and he went on to investigate the nature of deliberative discourse. A public that can communicate with itself, gathering informally beyond the professionalized sphere of party politics is what political philosophers imagine informing “strong democracy” (Barber, 1984).

This kind of a public is created by communication in public life. Dewey and Habermas, among others, built their arguments about public life on an insight alive in a long philosophical tradition: communication creates community (Depew, 2001). People construct relationships through communication, and the nature of the communication shapes their relationships. A democratic public needs individual access to knowledge – it needs to be an “informed citizenry.” But that is not enough. A democratic public needs places both physical and virtual to go, information habits in common and common understandings.

Our mass media, designed as a one-to-many distribution system, act as a “pseudo public sphere” (Chanan, 2000), where public discussion may be mimicked or modeled, but most viewers cannot usually join in. Social documentaries engage this pseudo public sphere on its own terms, and also attempt to reach through, around and beyond it, to participate in and encourage a true public sphere. As a form featuring both story and conversation in service of public knowledge and action (Nichols, 2001), they both challenge the reality status quo and address themselves to publics.

Moreover, they cumulatively act, with other public media expressions, to create new cultural expectations. Media that are now accepted and routine – NPR-style and Lehrer NewsHour-style news, investigative television programs, quality children’s programs – have built both audiences and cultural practices from zero within the last two generations. Social documentary practices add up to more than the sum of their parts.

SQUEEZING THROUGH THE GATES: PROFESSIONAL PRODUCTION FOR TELEVISION

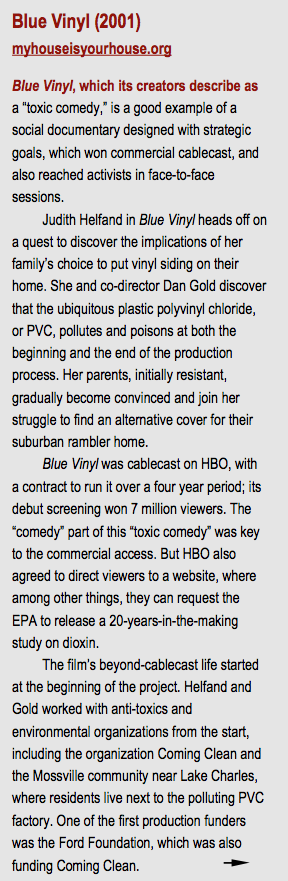

Stanley Nelson’s 2003 The Murder of Emmett Till was carried nationally on public TV via the popular strand American Experience. After its airing, 10,000 postcards and letters to Mississippi Attorney General have added to the campaign to reopen the case. Judith Helfand and Dan Gold’s 2002″toxic comedy” Blue Vinyl, which has shown repeatedly on HBO, explores the deadly pollution created by polyvinyl chloride. As a result of an audience campaign at its debut at the Sundance Film Festival, the bath supplies company Bath and Bodyworks has agreed to stop packaging its mail order goods in vinyl. Jonathan Stack and Liz Garbus’ 1998 The Farm, about life prisoners in a Louisiana prison, was shown on A&E and shown to prisoners’ families and in prisons throughout Louisiana, engaging viewers in discussion of the death penalty and sentencing practices.2

Some social documentarians, recognizing the enormous reach and impact of mass media, create work destined for television and theaters. They see themselves as intervening in the daily media diet of Americans, and offering both more information and another way to see the universe of possibilities. They might hope to have viewers change habits or opinions, share information, discuss a problem, or learn more about an issue.

To do so, they must negotiate with the gatekeepers with the tallest and best guarded gates in a highly competitive media environment, largely dedicated to entertaining viewers. The space inside is valuable because it is an arbiter of shared reality. Social documentaries hold a prestigious place on that landscape, although they are not usually the high-rated programs. Peabody, Sundance and Academy Awards for documentaries regularly favor social documentaries over other, more commercial documentary formats such as nature and docu-soaps, and they favor the voice of independent creators over works that fit into highly formatted cable genres. Still, work shown on the prime screens – theatrical screens and national broadcast and cablecast TV – is powerful storytelling, made with a keen awareness of the conventions of the genres, and with respect for craft. Viewers watching these prime screens expect sophisticated craft and art, and gatekeepers select for it.

Business environment

Gatekeepers’ decisions are inevitably driven by profit-and-loss realities of the entertainment industry, which are rarely favorable for social documentaries. Theatrical release is extremely rare; even niche-market chains such as Landmark select for shows that young professional and middle-aged couples are likely to find amusing. Michael Moore’s spectacular success (Roger and Me; Bowling for Columbine) has long been the exception that proves the rule. His successes may create new opportunities for others, as it seems to have for Spellbound and Capturing the Friedmans, two 2003 documentaries that won theatrical showings.

There are other exceptions as well. Kartemquin Films’ Hoop Dreams, a sobering film about the American dream that follows two young African-American boys through their struggle to become basketball stars – was widely shown in theaters, after Gene Siskel and Roger Ebert – Chicago critics eager to discover a new film and trump their coastal competitors – celebrated it before it even debuted. But many social documentaries have a short theatrical run qualifying them for Academy Award consideration, and either break even or lose money. For instance, Long Night’s Journey into Day, a much-lauded and moving documentary by Deborah Hoffman and Frances Reid about the Peace and Reconciliation commission process in South Africa, played theatrically with success and rave reviews in several countries without making money on the theatrical runs.

Festivals provide cachet and visibility, leading to promotional opportunities. There are hundreds of them, and it is easy to get accepted to many, especially those that do not function as markets (Coe, 2002). They do not pay, however, and most do not provide serious market opportunities. The Sundance film festival remains the touchstone event for social documentaries aimed at theatrical and TV; competition is brutal. Some 1,300 documentaries competed for 18 competition slots at Sundance in 2002.

International markets, some theatrical but mostly broadcasters in Europe and Japan, typically shy away from U.S. social topics. When they buy, they usually pay low prices that reflect the size of their broadcast audiences (Rofekamp, 2002).

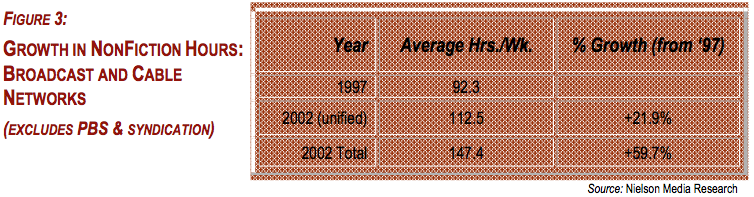

Documentary programming has grown dramatically with the rise of cable networks (see Figure 3). Worldwide revenues for documentary production in 1984 totalled about $30 million; in 2002 they were nearly $4 billion, and the sector had been renamed “factual-programs,” to encompass reality TV and docu-soaps (Hamilton, 2002). Documentaries that feed this business are usually highly formatted and branded, though. Networks have tight budget formulas and final cut. Subject matter – health, crime, sex – is typically stripped of a social action agenda. Court TV, TRIO, MTV, Lifetime and Discovery Times all offer small windows of opportunity for social issues. Investigative network programs such as Dateline and the venerable 60 Minutes all feature social issues, but usually within a rigid, detective-style format that resolves upon finding the bad guy. Nightline has, exceptionally on public TV, used segments from independent filmmakers within its issue- discussion format. An occasional program on social issues appears on the A&E cable channel (for instance, Jonathan Stack and Liz Garbus’ The Farm). HBO, whose subscription business model permits it investment in challenging topics, has aired social documentaries as part of its quest for awards: Calling the Ghosts, a film that became part of Amnesty International’s campaign to recognize rape as a war crime, Long Night’s Journey into Day, which showcased the South African truth and reconciliation commissions; and Blue Vinyl (see sidebar). But in 2002, according to Nielsen, there was not a single social documentary in the top-rated 20 cable documentary programs.

The most important location for social action programming is public TV, far friendlier to social-issue and underrepresented-voice productions than commercial television. On public television, a few public affairs filmmakers with impressive reputations, including Bill Moyers and Roger Weisberg, have  produced provocative, controversial work that both informs citizens and provokes action. Some social documentaries are stand-alone specials, such as Moyers’ controversial and powerful Trade Secrets, an indictment of the chemical industry both for toxic pollution and for covering up its role in creating it; and the two-hour People like Us (see p. 21), which boldly showcases the role of class in American culture. Some fit into series. Public TV’s series for independent producers, Independent Lens and P.O.V., both regularly feature social action documentaries. Social documentaries also appear on other series such as Frontline and Nova, and international series Wide Angle often features international documentaries. Each of these program strands has websites that link knowledge and action.

produced provocative, controversial work that both informs citizens and provokes action. Some social documentaries are stand-alone specials, such as Moyers’ controversial and powerful Trade Secrets, an indictment of the chemical industry both for toxic pollution and for covering up its role in creating it; and the two-hour People like Us (see p. 21), which boldly showcases the role of class in American culture. Some fit into series. Public TV’s series for independent producers, Independent Lens and P.O.V., both regularly feature social action documentaries. Social documentaries also appear on other series such as Frontline and Nova, and international series Wide Angle often features international documentaries. Each of these program strands has websites that link knowledge and action.

Even public TV has trouble making much room for social documentaries, mostly because of its peculiar structure. Public TV’s main funders are taxpayers, represented by legislators; members; and corporations. Controversy can make legislators hold hearings, members cancel their membership, and corporations reluctant to underwrite. Moreover, public TV is sprawling and centerless. Its hundreds of stations all control their own program schedules, although only a few have money to produce. The Corporation for Public Broadcasting channels the federal funds that make up about 12-15 percent of public TV’s budget, mostly giving it directly to stations. It gives also money annually to five programming organizations representing federally-sanctioned ethnic minorities (these are the “minority consortia” [Okada, 2003])3 and to the Independent TV Service. Minority producers have charged that CPB’s funding policies marginalize minority issues, faces and cultures (Haddock, 1998), zoning them into “themed” funding and programming areas. ITVS, created via independent producer pressure to serve underserved audiences with innovative programming, commissions  many social documentaries, but must persuade stations or the Public Broadcasting Service (PBS) to air them. PBS is a membership organization, whose members are stations; its job is to package programs for them. Stations only agree to show two hours a night at the same time, limiting national promotion.

many social documentaries, but must persuade stations or the Public Broadcasting Service (PBS) to air them. PBS is a membership organization, whose members are stations; its job is to package programs for them. Stations only agree to show two hours a night at the same time, limiting national promotion.

The arcane structure means that there are many people and reasons to say no to programs that might ruffle anyone’s feathers. Public TV is not required by law, after all, to provide challenging material to citizens; stations are only required not to air commercials (and even then, underwriting credits can come very close to advertising). It is a credit to the ingenuity and commitment of some public TV staffers that so much has been accomplished within a structure so hobbled from its origins.

Filmmaker Jeff Spitz, creator of The Return of Navajo Boy, a film about radiation exposure of Navajos in mines on their reservation (navajoboy.com), recalled his struggles. When the film was shown in Washington, D.C., and later on PBS’s Independent Lens series, it helped win support for the Radiation Exposure Compensation Act (RECA) legislation, he said, and it triggered a federal investigation into uranium stored on the Navajo Nation. It also moved the U.S. Department of Justice to pay out a $100,000 RECA claim to a former uranium miner whose case was features in the film. But initially, when he took it to the public TV station KEET in Arizona – the locality most centrally affected – the programmer had refused to carry the program, saying: “Cracking good story for a half hour, but please remember, in our market uranium is not pledgeable.” (After the film premiered at Sundance and the Associated Press reported extensively on the film’s subject matter, KAET-TV did in fact air the documentary  in prime time.)

in prime time.)

Other public windows are far more marginal than public TV, for professionals looking to reach broad mass audiences. Link TV (linktv.org) and Free Speech TV (freespeech.org) operate on satellite TV channels open to the public by law. Link TV provides a mix of upscale art films, selected ITVS programs, international news, and socially-engaged programming. Free Speech TV, a left-leaning, low-budget, grassroots strand of programming that mixes original and acquired work, and also shows it on cable and the Internet (see p. 34). Both make token payments. Cable access channels carry locally-produced programs or or programs made elsewhere and locally-sponsored, for free. Viewers without personal video recorders are hard-pressed to find program schedules.

Winning broadcast and cablecast can uniquely bring a subject or issue into the “pseudo-public sphere” of mass media, where issues take on crucial mainstream currency. But in a multichannel, multi-screen world, where viewers are plagued by what one researcher aptly called “data smog” (Shenk, 1997), a good publicity and promotion plan is needed. Too often neither the filmmaker nor the public TV station or cablecaster has the resources for the critical attention-getting that turns the social documentary into an event, and that in itself helps to change cultural expectations. The millions that General Motors added to the budget for Ken Burns’ Civil War for publicity and promotion had a dramatic effect; sadly, corporate resources are unimaginable for most social documentaries, and even for series and strands that feature social documentaries.

After broadcast

The “pseudo-public sphere” of mass media can also be powerfully leveraged for civic or community engagement. This engagement, or what some call broadcast outreach when it is associated with a television showing, has steadily grown in sophistication over the last decade. Community engagement means finding groups that care about the documentary’s concerns and helping them use it – either on broadcast or off-broadcast – to further their goals.

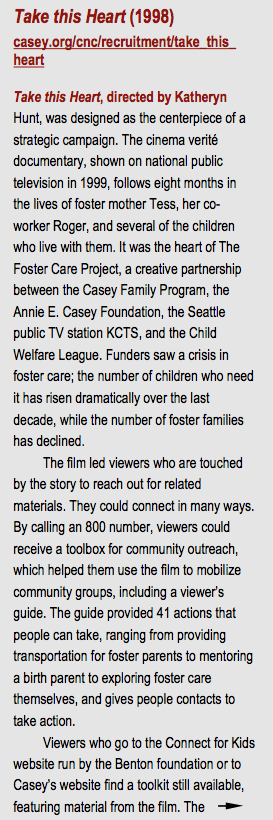

Outreach models for broadcast have been developed over two decades by several organizations. Public television’s P.O.V. has developed an impressive, labor-intensive model for outreach, which uses national and local partnerships, feedback mechanisms, and Internet interfaces. It also builds relationships within public TV. With Two Towns of Jasper, for instance, P.O.V. succeeded in getting the filmmakers placed on Oprah, and having Nightline host a town meeting on racism (see sidebar) (West, 2003). The documentary Take this heart, a profile of a season in the life of a foster parent (see p. 56), was designed to be used with foster groups in communities across the country, with public TV stations as the liaison.

Several enterprises have developed different approaches to broadcast outreach. For instance, Active Voice (activevoice.org, part of P.O.V.’s parent organization) specializes in highly tailored relationships with  community organizations and face-to-face events. Outreach Extensions depends on longstanding relationships with national service organizations. Working Films (workingfilms.org) selects films with a strategic social action agenda, and develops programs for change that begin, ideally, with the production of the film. Other organizations include Roundtable Media (roundtablemedia.org) and public television’s own National Center for Outreach (nationaloutreach.org), which offers an annual conference for station representatives to learn from each other.

community organizations and face-to-face events. Outreach Extensions depends on longstanding relationships with national service organizations. Working Films (workingfilms.org) selects films with a strategic social action agenda, and develops programs for change that begin, ideally, with the production of the film. Other organizations include Roundtable Media (roundtablemedia.org) and public television’s own National Center for Outreach (nationaloutreach.org), which offers an annual conference for station representatives to learn from each other.

The mass media window also leads into the classroom. School and college teachers are voracious users of media and media literacy materials. Distributors create and cultivate these markets. Several dozen distributors specialize in various aspects of the professional (medical, social work, legal) and higher education markets, all with their roots in ’60s and ’70s activism. Such companies as California Newsreel, Women Make Movies, New Day Films, Fanlight, First Run Icarus, and Cinema Guild have created niche markets (Block, 2002; Richardson, 2002). Until now, home video has been unviable, because markets were too small to sustain such low prices; growing consumer appetites for DVD rentals and purchases, though, may change that.

Other organizations also help viewers find social documentaries. National Video Resources (nvr.org) creates study guides and topics guides. Filmmakers themselves often create websites designed to support learning activities with their work. The PBS website offers remarkable search tools to lead teachers to their products, and PBS also permits teachers to tape all its programs off-air for a year. MediaRights.org’s database of social documentaries offers a way for users and makers to connect, as well outreach toolkits and valuable information on how others have succeeded. Distributor  databases such as that housed at docuseek.org also help educational researchers. Amazon.com often functions as a makeshift search site for media hunters.

databases such as that housed at docuseek.org also help educational researchers. Amazon.com often functions as a makeshift search site for media hunters.

Everyone would like the equivalent of a simple Google topic search that would guide a searcher to a social documentary – or even to clips or images. The software to make that happen, as well as the library cataloging that would help libraries worldwide share information about audio-visual material, is still around several corners. Meanwhile, public TV is at least standardizing its terms of reference for programs, to help stations manage their own digital assets. This is a first step toward a more viewer-friendly searching environment.

Resources

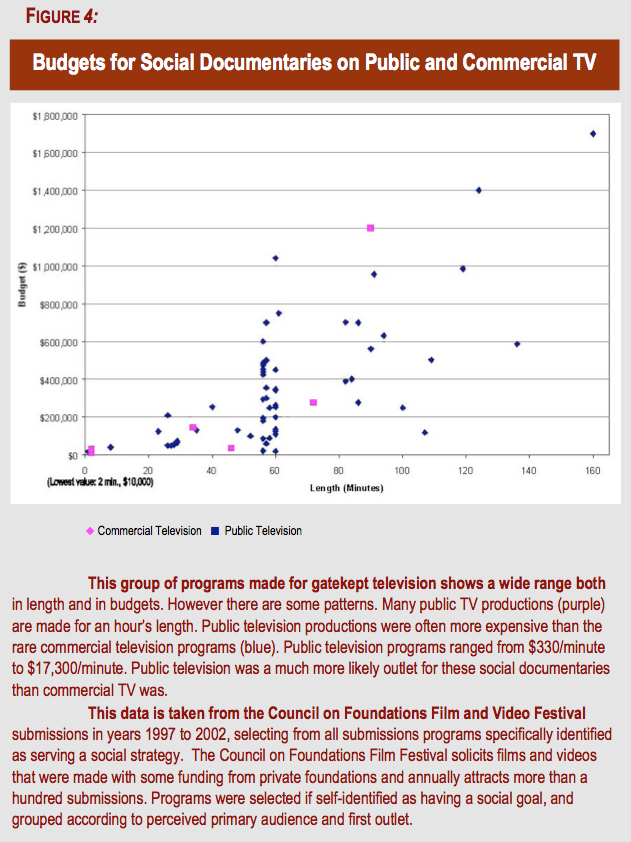

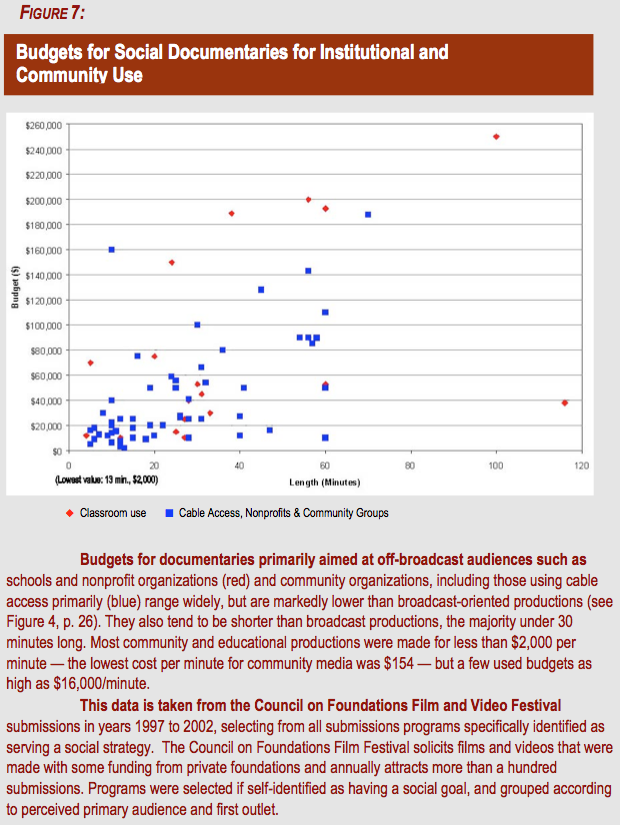

Social documentaries destined for television have a wide range of budgets, and can cost anywhere from $75,000 to $1 million an hour. (See Figure 4, p. 26) Filmmakers rarely make a profit on social documentaries, and they often invest substantial amounts before public or private funders contribute. The process is fed by commitment, since filmmakers encounter what Mira Nair – who abandoned documentary for feature filmmaking – called “a mountain of rejection” (Lahr, 2002).

Public funding is important and imperiled. Funding from public television, mainly through ITVS, minority consortia, and from rental fees from strands such as as P.O.V. and Independent Lens, is critical to many first or second-time filmmakers. Other public funds important to filmmakers have come from humanities and arts endowments, but the culture wars savaged their budgets, with media coming under especially tight scrutiny. The NEA and NEH only target media arts for a small portion of their total funding (see Figures 5, 6, p. 30). Since 1996, NEA contributions to media arts have declined 90 percent, as the agency has been forced under political pressure to drop its individual grants to filmmakers (Alexander, 2000). The NEH’s budget oriented to media projects has been cut in half since 1995 (Adams, 2001). Most state humanities and arts councils provide small amounts of money, which nonetheless are highly useful to launch work.

Private and commercial resources, important to documentary filmmaking generally, are spottily available for social-issue documentaries. Major foundations have supported some projects entirely, when the subject aligns with their specific program areas, but more commonly they contribute a portion. International television pre-sales and co-productions that are important to documentarians generally (Block, 2003) are hard for social documentarians to win. Professionals see the market for high-quality social documentaries as either stable or shrinking. The primary market (public TV or HBO) buy very few, and secondary broadcast markets pay very little (Rofekamp, 2002).

Despite these difficulties, many filmmakers every year decide to undertake such work. At the Independent Television Service, one of the places most likely to fund such work, 1,200-1,400 people apply each year (with only 2 percent ultimately finding funding). These numbers also reflect the enthusiasm of many first-time makers with their new digital camera.

Success

The advantages of the broadcast-oriented model are clear: mass media reach many people, and mass media information shapes people’s understanding of reality outside their own experience. In a society where mass media mimic the public sphere, and at the same time mostly entertain, the presence of a social documentary in that space is an important achievement. The broadcast or cablecast opportunity can make community engagement possible. Furthermore, mass media gatekeepers’ stamp of approval gives the documentary a long life in classrooms and communities.

The limitations of the model are several. Social documentaries are by far the exception, not the rule. Not only are they difficult to get on the air, but they can easily get lost without extensive promotion. Tying action to a broadcast has meant linking activity to a screening time, although personal video recorders will change this. Many public television stations do not have extensive community relationships, and very rarely do they have their own funds to do outreach on anything but children’s programs. Finally, a program that successfully attracts viewers at Sundance or on prime-time PBS may have a very different shape than a documentary suitable for a classroom or a community group (Daressa, n.d.).

The most typical measurements of success are, appropriately, those used by other mass media outlets to measure audience reach: ticket sales, ratings, hits on related websites, and anecdotes – all several steps removed from the goal, but all rough indicators of the amount of attention that has been paid. Public television’s overall primetime ratings are low – less than 2 percent of national viewership – and declining. Some 47 percent of households, however, according to America’s Public Television Stations, encounter it sometime in the week, and for social documentaries,  audiences skew toward decision makers. Cable TV channel ratings are often lower than public TV’s; its demographics for social documentaries also skew older and higher-income than average. Press coverage is also an important measure, not only to attract attention to the documentary but to the issue. For social documentaries designed for broadcast, industry measurements are both useful and appropriate. Their first window of release occurs within the one-to-many, “pseudo-public sphere” of mass media, where demographics and numbers are critical.

audiences skew toward decision makers. Cable TV channel ratings are often lower than public TV’s; its demographics for social documentaries also skew older and higher-income than average. Press coverage is also an important measure, not only to attract attention to the documentary but to the issue. For social documentaries designed for broadcast, industry measurements are both useful and appropriate. Their first window of release occurs within the one-to-many, “pseudo-public sphere” of mass media, where demographics and numbers are critical.

Reaching beyond the pseudo-public sphere means designing a strategic campaign, for community or civic engagement. Evaluation measures of this kind of work are far more challenging, although there are many guides to evaluation techniques for nonprofit projects of all kinds (Kellogg Foundation, 1998). The social documentary becomes a tool of the strategic process to be analyzed.

Another measure, however rough, of social value is the social diversity of both subject and maker – ethnic, gender, class, disability, regional and other social categories widely seen as “underserved” in mainstream media. Documentary filmmakers whose work appears on public television are assuredly more culturally and ethnically diverse than the larger pool of professional filmmakers. The existence of minority consortia and of the ITVS alone demonstrate a greater emphasis on diversity than in commercial TV. Leading and pioneering works of cultural history such as the African-American series Eyes on the Prize, the history of Chicano migrant workers’ organizing, The Fight in the Fields, and Chinatown Files (see page 27) are evidence. No public data support this conclusion, however, since data collection on diversity is proprietary and not even public TV organizations share this data.

American social documentarians are able to draw on a legacy of courageous investigative, expository and verité creative work as they confront the challenge of engaging the American public on important social issues. They produce the leading edge of programming that challenges commercial construction of reality in the heart of mass media – television.

NO GATEKEEPERS: ALTERNATIVE MEDIA

At OneWorld.net, Amnesty International has posted documentary footage of its visit to the Free Prisoner Association, a human rights group in Iraq. At Big Noise Media, anti-globalization activist filmmakers recount the history of the Zapatista movement in Storm from the Mountain. On Free Speech TV’s free digital satellite channel, independent filmmaker Norman Cowie runs his critique of U.S. foreign policy, Scenes from An Endless War.

In dramatic contrast to the professional zone of mass media, “alternative media” creates an open, unstructured, gatekeeper-free environment for social documentaries. The current openness of the Internet is exploited to market new media, transmit it, and to engage viewers. This is “media production that challenges, at least implicitly, actual concentrations of media power” (Couldry & Curran, 2003). Alternative media have been seen, correctly, as expressions of people and cultures whose voices have been excluded from dominant media (Atton, 2002; Zimmermann, 2000), as important for their signaling of discontent and demand for justice as for their demand to express themselves. There is also a tradition among activists of celebrating do-it-yourself approaches to media making, for their saucy spirit of resistance (Halleck, 2002), a theme that has also been present in cultural studies. Although they sometimes claim to be creating alternative programs for general interest viewers or to reach decision makers, alternative mediamakers often serve and cultivate sub-communities, rather than the broad audiences that gatekept TV reaches.

Background

The creation of alternative media has been a dynamic element of rights movements of the last three decades. Feminists from the early 1970s created formally-challenging, experimental work as well as videos for activists and informational-instructional videos on issues ranging from domestic violence to birthing care to workplace issues (Rich, 1998; Juhasz, 2001). The core audience for such work was other women. In the 1980s, AIDS activists created film and television for and with the growing movement demanding more social resources to address the public health crisis (Juhasz & Saalfield, 1995), and gay and lesbian subcultures featured work by and for these communities (Holmlund & Fuchs, 1997). Ethnic media have accompanied and fueled movements for full democratic participation by cultural minorities in the U.S., building communities and audiences simultaneously (Noriega, 2000; Klotman & Cutler, 1999). Artists and activists shared a passion to explore modes of expression that would break with mainstream commercial and televisual conventions, as well as content that reflected the new voices clamoring to be heard in the society (Boyle, 1997).

Traditional commercial media products and processes have been a prime target of alternative media. In fact, alternative media criticism has taken on its own name, of culture jamming (Klein, 2000). In this movement, 60s alternative culture activists and today’s anti-globalization activists find common ground in resistance to corporate media culture (Shepard & Hayduk, 2002). At the same time, culture jammers are fascinated by the power of commercial media itself, and determined to subvert mass media claims to transparent realism.

Paper Tiger, an alternative media production group, developed a highly publicized profile that became emblematic of the oppositional spirit of “alternative” TV.  The Paper Tiger TV Collective in New York City, born in the early 1980s, develops productions, conducts community screenings, and conducts training to raise awareness about the social implications and impact of media. Its productions typically are purely volunteer, with only the crudest of props and tools. A recent Paper Tiger production, Fenced Out, was part of an organizing effort to save the Christopher Street Piers, a rare place in New York City where young people of color and lesbian, gay, bisexual and transsexual youth congregated, from redevelopment. Another longstanding example – sustained for many years by University of Texas professors including Douglas Kellner – was the program “Alternative Views” on Austin public access cable TV. In Portland, Oregon, video collective Flying Focus’s weekly half-hour cable access series, The Flying Focus Video Bus, includes subjects such as police brutality and critiques of mainstream media. Its lecture series includes Noam Chomsky on the Media & Democracy, Barbara

The Paper Tiger TV Collective in New York City, born in the early 1980s, develops productions, conducts community screenings, and conducts training to raise awareness about the social implications and impact of media. Its productions typically are purely volunteer, with only the crudest of props and tools. A recent Paper Tiger production, Fenced Out, was part of an organizing effort to save the Christopher Street Piers, a rare place in New York City where young people of color and lesbian, gay, bisexual and transsexual youth congregated, from redevelopment. Another longstanding example – sustained for many years by University of Texas professors including Douglas Kellner – was the program “Alternative Views” on Austin public access cable TV. In Portland, Oregon, video collective Flying Focus’s weekly half-hour cable access series, The Flying Focus Video Bus, includes subjects such as police brutality and critiques of mainstream media. Its lecture series includes Noam Chomsky on the Media & Democracy, Barbara  Ehrenreich on War and Society, and Howard Zinn on Reclaiming the People’s History. Its budget comes close to zero; volunteer passion is crucial. Besides running on the local public access television channel, the collective also distributes tapes by mail from a catalogue of more than 300 titles, and runs local lending libraries, catering to aspiring anti-corporate organizers.

Ehrenreich on War and Society, and Howard Zinn on Reclaiming the People’s History. Its budget comes close to zero; volunteer passion is crucial. Besides running on the local public access television channel, the collective also distributes tapes by mail from a catalogue of more than 300 titles, and runs local lending libraries, catering to aspiring anti-corporate organizers.

Alternative media producers have ridden the crest of new technologies, often enabled by policies that mandate public use of them. For instance, the cable access movement that began in the 1960s (see next chapter) was a powerful spur to such work, because for the first time it created channels of access for a general public to the prized home screen of television. The cable access movement spurred grassroots and self-styled alternative production projects nationwide (Fuller, 1994). Satellite television’s public channels, also created through citizen pressure, have also provided screens for alternative media. Finally, the Internet, created in a government research project, has mobilized new media activists.

The documentaries made within alternative media generally engage already-mobilized organizations and small groups. In 1991, Deep Dish TV (deepdish.igc.org), a volunteer organization that uses available satellite transponder space to upload programs to cable systems nationwide, distributed nationwide a series of programs in opposition to the Gulf War. These programs were used most often by groups already mobilized against the war or by organizations eager to hear that perspective. (During the U.S. invasion of Iraq in 2003, Deep Dish activists considered launching an initiative but could not assemble resources in time.) Activists of all types have seized the video as a tool for their causes. For instance, James Ficklin, a producer working with anti-globalization  activists and tree-sitters in the Northwest, describes his own activist videos as “educating the converted,” providing arguments and information that bring enthusiasts into the movement. This is an approach detailed with extensive examples in Thomas Harding’s The Video Activist Handbook (Harding, 2001).

activists and tree-sitters in the Northwest, describes his own activist videos as “educating the converted,” providing arguments and information that bring enthusiasts into the movement. This is an approach detailed with extensive examples in Thomas Harding’s The Video Activist Handbook (Harding, 2001).

With the growth of the Internet, countercultural work has followed. A “D.I.Y.” (do-it-yourself) ethic has fueled enterprises that purvey alternative media, which exist thanks to the commitment of their founders, such as Guerrilla News Network (gnn.tv), People’s Video Network (peoplesvideo.org), Video Activist Network (videoactivism.org), and the burgeoning blog phenomenon.

Indymedia

Hundreds of efforts draw from the Independent Media Centers (indymedia.org), or “indymedia,” the astonishingly protean network of social activists using the Internet both to communicate and to organize. Indymedia centers have sprung up, now more than 125 of them in some 25 countries since its dawn in Seattle in late 1999, as a result of anti-globalization protests at a World Trade Organization meeting (Kidd, 2002). That movement drew on the expertise and contacts of older media activists including those involved in Paper Tiger, who shared an anarchic sensibility (Halleck, 2002b). As “evan,” an indymedia activist, put it, “Indymedia draws its content and ideas from within active participants themselves. This is why we say ‘be the media.’ We are creating media labs, video editing rooms, radio stations, websites, community newspapers, and other media to be a space in which discourse can take place.”

Indymedia sites have both made use of streamed media and also become retail sites for video. The Showdown in Seattle: Five Days that Shook the WTO, created by a coalition including Deep Dish, Paper Tiger, FreeSpeech TV, Whispered media, Changing America, and New York Free Media Alliance, was seen on television, streamed, and is used in anti-globalist organizing. 9-11, made in New York within a week of the attacks on the Twin Towers, is available in video and streamed media, via the FreeSpeech website.

Indymedia makers often espouse anti-professional, movement rhetoric, seeing their work as responding to and fueling social protest. For instance, Big Noise Productions’ manifesto reads:

We are not filmmakers producing and distributing our work. We are rebels, crystallizating [sic] radical community and weaving a network of skin and images, of dreams and bone, of solidarity and connection against the isolation, alienation and cynicism of capitalist decomposition. We are tactical because our media is a part of movements, imbedded in a history of struggle. Tactical because we are provisional, plural, polyvocal. Tactical because it would be the worst kind of arrogance to believe that our media had some ahistorical power to change the world – its only life is inside of movements – and they will hang our images on the walls of their banks if our movements do not tear their banks down.

Thus, Big Noise measures its success on the basis of its service to a struggle against the powers maintaining the status quo.

Big Noise’s videos draw from international indymedia documentration to celebrate the spirit of anti-globalization demonstrators and describe them as an “anti-corporate” force for peace and justice. In Fourth World War, for instance, producers compiled images from indymedia groups around the world – Argentina, Palestine, Seattle, Genoa – to create a collage film with a music-video like track (contributed to by rappers and other popular music groups), melding images of protestors from different continents and layering images of Mexican indigenous peasants onto Seattle and Genoa demonstration footage. Narration, read by poet Suheir Hammad and musician Michael Franti, asserts that “the world has changed” and that “we” are joining protestors everywhere.

Indymedia producers have been far less open-handed with producers who are not part of their own networks and circle of belief. For instance, German investigative journalist Michael Busse made a film investigating the role of Italian police in instigating violence during the bloody 2001 anti-globalization demonstrations in Genoa, Italy. Storming the Summit, shown on German public service TV, draws on the work of dozens of amateurs who videotaped the events, often comparing several shots from different angles of the same incident. It harshly indicts the Italian police both for causing violence and failing to control it.

Busse found both Italian and German indymedia outlets impossible to work with (Busse, personal communication, November 15, 2003). Italian indymedia producers refused to let him reuse their original material (which, unlike that of consumer videotapes, was broadcast quality), and only wanted to let him use a half-hour work if he used it in its entirety. In Germany, he found indymedia producers reluctant to share documentation that could be used to show that protestors had acted violently, and they also cut out images that could be used to identify individuals. Finally Busse used Internet searches to find individuals outside indymedia networks who were willing to share their tapes. Thus, in this instance indymedia makers were concerned primarily to use their video storytelling to tell only their own version of the story.

Indymedia centers, with horizontal decisionmaking structures and openness to all volunteers, have become entry points to many new, and often young people. At the same time, indymedia sites have found themselves hamstrung by their own anarchy, as they have grown past the moment of the 1999 demonstration (Halleck, 2002b, p. 65). In 2002, indymedia sites worldwide found themselves attacked by anti-Semitic, racist and conspiratorial contributions. While some suspected a coordinated attack to discredit indymedia and the IMC Global Newswire collective made recommendations to protect indymedia sites from attack, local volunteers failed to implement any coordinated action.

Other alternative sites for social documentary

Many projects join a rejection of mainstream commercial media, fascination with new technologies, and the Internet’s capacity for interaction. DVRepublic.com, a project of the Black Filmmaker Foundation, mentors and encourages “socially concerned filmmakers of color to present their stories, ideas, and images on their own terms without seeking the permission, approval, or sanction of media gatekeepers.” For instance, Tania Cuevas-Martinez and Lubna Khalid’s Haters, the first finished work at DV Republic, chronicles racial profiling and hate crimes after Sep. 11, 2001. Calling itself a “liberated zone in cyberspace,” DVRepublic uses the Web to promote and sample work that can be ordered in video. It also fosters a discussion list around the work, and activist links, for people who reject the “artistically exhausted and politically insidious” mainstream of American TV and film. Thus, the project hopes to generate a community of users who will also be consumers of its niche product and provide enough revenues to keep it alive.

Other work draws from the “digital storytelling movement,” as the Center for Digital Storytelling (storycenter.org) in Berkeley, CA calls it. Community organizing efforts employ media to permit people to discover the stories in their lives, and thus build and strengthen relationships and their ability to act in their own communities and lives. People create small digital movies, audio files, slideshows and other media. Their stories may be about surviving child abuse, or about being young, gay and Latino, the life of one interracial family, or about organizing to resist racism in one community (digitaldocumentary.org). Third World Majority (cultureisaweapon.org) is one example of such a project, focused on people of color. “Even those within the industry recognize that mainstream media’s trickle-down approach to storytelling poses important concerns about the legitimacy of the information, and compromises the notion of open, accessible, and balanced information,” its website declares. The process itself acts as a forum “for communities to tell their own truths in their own voices.” The stories are usually developed within workshops that also develop action agendas. Storylink.org, a project in development in 2003, intends to provide a common platform for digital storytellers of all kinds to view each others’ stories, link to them, and create their own.

Although the anarchic, obstreperous voice of left critics of capitalism have been highly visible in alternative video and film, other ideologically-driven communities have seized their opportunities as well, and created national networks. Christian fundamentalists have developed extensive product lines and distribution networks. Books, audio and, to a lesser extent, video by Tim LaHaye on the Rapture have sold by the tens of millions, turning Tyndale Press into a publishing powerhouse. The highly publicized success of Al Quaeda’s recruiting videos also demonstrates the power of ideologically-driven video with an institutional base.

Some alternative media have strategized how to use the strength of networks of communities of belief to reach beyond them, into public life. MoveOn.org, which uses the Internet to build “electronic advocacy groups” for liberal and left perspectives on public issues, has had unparalleled success with “viral marketing” – the rapid spread of information through friends-and-family-list emailing. Since its origins in the attempt to counter Republican attempts to impeach President Clinton, MoveOn has moved from a small, partisan organization to a voice of protest to be ignored by politicians at their peril. It provides its email recipients with information, something to do, and often somewhere to go to discuss or debate an issue; it has become a force of public opinion. MoveOn uses social documentaries to stir public debate. It claims to have distributed 100,000 DVDs of professional filmmaker Robert Greenwald’s Uncovered: The Whole Truth about the Iraq War in a few weeks in October-November 2003; the distribution of these videotapes was intended to expand informed discussion of the war at election time. Thus, MoveOn’s use of video not only creates community, but also fuels public discussion.

The networked, Internet-based independent media site OneWorld also directly confronts the challenge to reach “beyond the converted.” It aspires to provide information to diverse audiences, and also to cultivate virtual communities of people committed to social justice. It has a management structure, editors, and criteria for membership. Its showcase for social documentary is also a moderated and managed public platform (see p. 32). OneWorld serves both a community and publics beyond it. For instance, in November 2003, OneWorld excerpted Portia Rankoane’s A Red Ribbon around My House, a film on AIDS activism in South Africa made as part of the celebrated Steps to the Future series. It links the video with news about South African AIDS activism, and to an open discussion board.

Resources

The resources that alternative media can draw on depend both on their relationships with institutions (for instance, an evangelical church network or Democratic party fundraisers) and their ability to use viral marketing to win individuals’ support. Budgets vary but they rarely reflect the real costs of the product. Resources for such work largely depend on the energy – usually youthful – of participants, occasionally boosted by foundation support. However, foundations can be stymied if structures are not reliable. For instance, foundations associated with RealNetworks initially backed indymedia in 1999, but were unable to sustain support because they could not identify leadership to receive and channel funds. Alternative media are often sustained by ever- new infusions of youthful energy. It is correspondingly difficult to have institutional memory, to develop skills, and to learn from mistakes.

Success, for communities and the public

Success is often equated, in alternative media, with survival (in this case, creation of a documentary) against the odds. There is also often, understandably for organizations running on enthusiasm, an emphasis on producers rather than on users. On the other hand, methods drawing on multiple measurement approaches are also being tried. OneWorld is developing an evaluation element to its work that includes not webhits and also audience surveys and focus groups, and that draws from development evaluation expertise; evaluation focus is on users.

In the ungated environment, networks grow along the lines of shared commitment and perspective. So a major challenge of most alternative media is reaching beyond a committed circle. That challenge is in the public’s interest, and also in the interest of the committed themselves. In a network analysis of niche and alternative media and movements, Manuel Castells (1997) notes that media can reinforce group self-identity, at the cost of linking with others and fully participating in the emerging “network society.” This is a familiar tension, and not one that new technologies resolve.

BUILD IT AND THEY WILL COME: PUBLIC PLATFORMS FOR NEW SPEAKERS

At regional media arts centers Appalshop, Mimi Pickering’s Hazel Dickens: It’s Hard to Tell the Singer From the Song both celebrates a regional musical artist and recalls working-class life and union struggles. At Chicago’s cable-access CAN-TV, an African-American couple make a series of African-American history programs. At a community computing center in Saint Julie Asian Center in Lowell, MA, Asian immigrants use computing resources to assemble Powerpoint slide shows for overseas members of their family, and the Center makes videos to add to English language classes.

In media arts centers, cable access centers, community computing and technology centers, and media programs associated with nonprofits, new speakers – young people, members of ethnic minorities, the poor, disabled and emerging community members – have been able to make their own media. There are now thousands of local centers across the nation, where community members are creating their own video and digital media work, showing it to each other, uploading and exchanging it with users worldwide. The National Alliance for Media Arts and Culture has hundreds of members nationwide, a mix of individuals and community media centers whether stand-alone or based in other organizations such as museums and service organizations.

While media arts centers grow out of film, cable access out of cable TV, and community technology centers out of computing, they increasingly overlap missions and even share resources and strategies. They often work with social service organizations, universities and colleges and religious organizations. These community media spaces are marked by their nonpartisan nature and their localism, welcoming and recruiting a wide variety of nonprofessionals to participate in their programs. Typically, community media stalwarts have a deep commitment to social justice, and see themselves as providing electronic commons or vehicles to expand diversity of expression, or as a service that amplifies and enriches civil society as a whole. Leaders commonly believe that the process of making a film or video can be as important as any final result. Media literacy, group interaction, public discussion, and skills acquisition are often goals as important to those who manage these production and distribution platforms as the finished expression.

Helen De Michiel, an independent filmmaker and the executive director of the National Alliance for Media Arts and Culture, describes the work of these organizations as “public media,” which she defines as pedagogical, “through which we can consciously learn about how to participate in democracy and civilization.” Public media culture, she writes,

lives close to the ground – in and around clusters, networks, and alliances of individuals in communities around the country….its art resides not only in the creation of media products (film, video, audio, or new digital hybrids) but in the design of organizational structures that attract and grow a diversity of expression not permitted elsewhere. It makes technological tools accessible and transparent enough for anyone to explore as it examines what those tools can accomplish and why they are used. And it is figuring out new ways to encourage citizens to become active participants in the process of media expression and dialogue…as creators of the very terms of that social and creative engagement (De Michiel, 2002, 5-6).

Background

These projects of community media all evolved from simply providing technical resources to building relationships for public media practices. They share a commitment to community development, knowing well that cultural enterprises feed community social and economic health (Dwyer & Frankel, 2002; Stern & Seifert, 2001).

Media arts centers, where community residents and schoolchildren can learn mediamaking skills, exhibit their work, and meet other mediamakers, were born in the Great Society era with enthusiasm for more portable and easier-to-use film and video technologies. Originally born in a joint project between the then-new National Endowment for the Arts and the American Film Institute, they were for years afterwards supported by the National Endowment for the Arts and the MacArthur Foundation, as well as local government and private funders.

Cable access channels are another important community media resource, which began with the twin goals of providing channel access and equipment access. They can now be found on many of the nation’s cable systems, especially in the larger cities, although it sometimes has taken years of organizing to get them. The Alliance for Community Media (alliancecm.org), the cable access center membership group, estimates there are 1,500 public access operations in the U.S., with about a million hours of programming produced annually. A generation of ’60s activists, empowered with a seemingly arcane law requiring cable operators to obtain leases for using rights of way, won clauses for such channels and money to support them in cable company contracts, or franchises, made with localities. The assumption that simply providing access would result in production and exchange of ideas has evolved into realization that relationships need to be cultivated, both with individuals and institutions. Training and mentoring are critical. They have by and large  developed far past the initial mandate to provide “first come first serve” access to individual citizens. Most have a kind of program service, with entrenched incumbents, and even syndication – for instance the Youth Channel. (Kucharski, 1999; ross, 1999; Manley, 2002)

developed far past the initial mandate to provide “first come first serve” access to individual citizens. Most have a kind of program service, with entrenched incumbents, and even syndication – for instance the Youth Channel. (Kucharski, 1999; ross, 1999; Manley, 2002)

Community technology centers began as places to overcome the “digital divide,” and stressed skills acquisition in computing, usually focusing on individuals. They developed with the help of local, state and federal funds for skills acquisition and economic development (Sullivan, 2003), and have taken root as projects within many organizations, as well as being standalone centers.

Managing public spaces

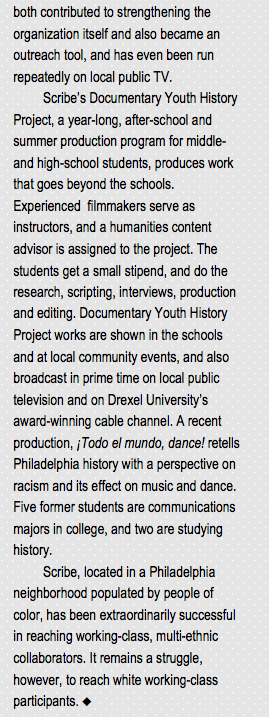

At media arts centers, often the first population of users was often white, middle class professional aspirants and artists. Media arts center directors reached past that core group by forming partnerships with social service organizations, organizing programs such as youth media and prison media, and by providing links to entry-job related skills. Media arts centers use a variety of models. The Scribe Media Center in Philadelphia targets social change-oriented nonprofits and provides mentoring (see p. 42). The results typically are used by the organizations themselves, though they also can get some local airtime. But not always. Appalshop (appalshop.org) in Whitesburg, Kentucky, a legatee of the original National Endowment for the Arts and American Film Institute project to start media arts centers in 1969, produces broadcast- and theatrical-quality video in conjunction with local Appalachian residents. Appalshop provides technical, artistic and professional expertise and controls the programming; the results showcase regional culture to both regional and national broad audiences. A third model is provided by the Media Working Group, originating in Cincinnati, Ohio. It acts as a loose collaborative of regional artists, who use the organization to lower administrative costs and as a platform to launch their own projects of social engagement. Results include teaching programs, regional broadcast programming, and a web-based training program in new media for grassroots artists. Yet another model is Minneapolis’ IFP-North, a legatee of the pioneering Film in the Cities program of the 1970s (which was one of the most successful grassroots-oriented skills programs in the country until its implosion in the early 1990s). It balances the missions of serving the professionalization needs of emerging filmmakers and encouraging grassroots expression.

Cable access staffers are acutely aware of the need to reconcile competing demands on the fixed capacities of their channels. They have long struggled with how to facilitate free expression without becoming a mouthpiece for one ideology. For instance the Ku Klux Klan during the 1980s took advantage of cable access to encourage local organizing via a nationally available video to be presented by local groups. This strategy is still encouraged by national organizations of all kinds. For instance the Christian religious video production house Eden Communications offers its videos free to anyone who will sponsor them on their local cable access channel, and Deep Dish also seeks new cable access outlets via local activists. Cable access has traditionally welcomed all new speakers, and encouraged more speech to engage these speakers.

Cable access centers usually aspire both to train new mediamakers and also to permit viewer access to new points of view and information. Paula Manley identifies four kinds of production that serve social action, produced at access centers: the voices and views of marginalized populations; nonprofit and grassroots groups; civic involvement productions; and organizing (Manley, 2003). Barbara Popovic, head of the extraordinarily successful Chicago public access CAN TV (cantv.org), argues that access channel programming provides a crucial information lifeline. “People do get excited about getting jobs, legal advice, math education for their kids, and health care assistance via television,” she noted. “Right now, the AIDS Legal Council of Chicago is live on CAN TV21 answering questions about AIDS in the workplace. That was preceded by a program about medicare benefits, and will be followed by a program with immigration experts answering immigration questions. These lifeline services have a presence on CAN TV every day.” The result, she noted, is passionate citizen support. An access-hostile bill in the state legislature, for instance, was defeated on the floor, because of citizen testimony – including that of a uniformed policeman bringing forward a petition.

The success of CAN TV reflects common wisdom in community media – that community relationships depend on institutional relationships, often with nonprofits that tap into communities. CAN TV has connected, by its estimates, with 2,500 of the 8,000 area nonprofits. Mentoring and training strategies that emphasize ongoing relationships are key. Palo Alto, CA’s Mid Peninsula Community Media Center also builds enduring relationships. The center has trained staffers or volunteers from 45 community groups in storytelling. As Manley notes, groups such as the Community Breast Health Project, the Junior League and the Clara-Mateo Homeless Alliance are paired with a videographer/editor to produce six short segments over the course of a year. These segments air on a regular program, Community Journal. Groups report both that they get good publicity and that they are able to use the pieces as stand-alones in advocacy and recruitment. And Denver Community Television’s “Your Message Here…” campaign, with the Colorado Association of Nonprofit Organizations, trains members of groups such as A Su Salud (To Your Health), United Way, and the MLK Day Celebration Committee to prepare organizational videos and computer-based media, as well as to do event coverage and studio interviews for cablecast.

Digital media creation tools, added to the Internet, have turned CTCs into nodes on communications networks that create new, virtual communities and “public spaces” (Schuler, 1996). Meanwhile, many institutions ranging from religious organizations to housing projects to youth groups have built digital media into their workshops and after-school programs. For instance, at Saint Julie Asian Center in Lowell, MA, Asian immigrants use computing resources to assemble slide shows for overseas members of their family, and the Center makes videos to add to English language classes (Davies et al., 2003; Sullivan, 2003). Unlike the mass media model that cable TV uses, CTCs bring a conversational, interactive mode to media making.

Resource challenges and new opportunities

Community media centers face common challenges, across technical platforms and mission statements. A 2002 survey of media arts organizations nationwide revealed general urgent concern over resources and mission, at the same time that new opportunities were identified. Participants in the survey noted that their school-service programs were disappearing with declining school budgets. New technologies were shaking up basic missions. Ad hoc efforts, fueled by accessible technologies, soaked up volunteer time and energy and often could lead to burnout. And of course they all faced declining taxpayer dollars or indirect benefits from them. (Manley, 2002)

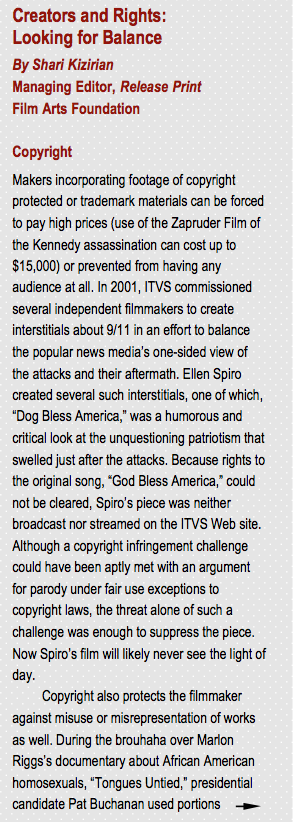

Media arts centers have encountered hard times from the later 1990s, with economic downturn, decline of taxpayer funds including from the National Endowment for the Arts, the MacArthur Foundation’s decision to stop funding such centers, and with the stresses of generational shift as baby boomer-era leaders step down. Some have undergone financial crisis (New Orleans’ NOVAC), others have disappeared, and some have grown and taken on new tasks. For instance, the Bay Area Video Coalition has become a source for preservation of video, a paying business and one that benefits nonprofits with affordable services and does workforce development.