Katie Donnelly

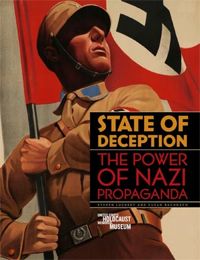

The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum (USHMM) recently wrapped up an initiative designed to helpteachers use its “State of Deception: The Power of Nazi Propaganda” exhibit to teach digital and media literacy skills.

The exhibit, according to the State of Deception website, “reveals how the Nazi Party used modern techniques as well as new technologies and carefully crafted messages to sway millions with its vision for a new Germany.” It includes a powerful online component, featuring an interactive timeline, a gallery of digitized artifacts (including books, audio, moving images and more) and a catalog of themes to explore. Each theme (“Making a Leader,” “Indoctrinating Youth,” etc.) combines explanatory text with historical artifacts and features such as short videos, slide shows, and interactive features (for example, see “The Many Faces of Hitler.”) The website also hosts a vast collection of resources, including lesson plans, historical sources and video features.

During January and February of this year, over 300 English teachers from across the country participated in a digital and media literacy online workshop that introduced the exhibit and key media literacy concepts through a combination of webinars, lesson plans and online discussions. Carol Danks and Laurie Schaefer, both Museum Teacher Fellows and members of the USHMM’s Regional Education Corps, an advanced teacher training program, facilitated the online workshop.

The initiative used the English Companion Ning, an online resource-sharing community for over 25,000 English and language arts teachers, as a platform. According to Peter Fredlake, Director of National Outreach for Teacher Initiatives for the museum, this platform was chosen because the museum’s educational team wanted to “engage the broadest number of people possible, and the potential for impact was really high.” In addition, the Ning platform provided a pre-existing structure and audience, making it “a perfect venue for experimentation.”

The goals of the workshop were to

The workshop included four modules, plus an introduction and conclusion. Each module instructed teachers on how analyze the themes on the website using the five critical questions of media literacy as a foundation. While the modules incorporate features of the site, Fredlake notes that lesson plans were developed with school Internet access issues in mind: “We wanted to make it more than just ‘click your way through our website.'” Accordingly, the lesson plans can be completed either on or offline.

On each module page, teachers were invited to reflect upon the information presented and share their own classroom experiences. Although the comments are now closed, the teacher feedback for each module is quite insightful, providing guidance for others who wish to teach about propaganda as well as potential evaluation data for the museum.

In order to better understand the teachers who participated in this program, the museum’s educational team employed a short survey after the completion of the program. Some of the data provided interesting insights: for example, the teachers overwhelmingly (79.7%) taught at public schools. Only 50% of survey respondents posted comments in the discussion forums, yet over 86% read the discussion forums. The survey results also indicated that teachers were likely to use downloadable content from the museum website but unlikely to interact with the social media features. While the survey focused more on understanding participants and the extent of their participation, it also invited participants to share their comments and criticisms, and provide input on potential material for future educational programming. Plans for future programming are not set in stone at the moment, but the museum may invite teachers back to share their classroom experiences implementing the curriculum on the English Companion Ning. Aside from this survey, the museum has not yet implemented a formal evaluation of the program.

In addition to its educational programs, the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum is working on more ways to engage people through media. For example, a “Propaganda Mobile Initiative” is currently in development. Holocaust survivor volunteers will guide visitors through the exhibit using a combination of cell phone voice recordings and interactive text messaging. Considering all of the new media emphasis at the museum, Fredlake says he “really like[s] the media literacy focus, because everything we do uses media: photos, documents, speeches, etc. We’re always engaging people with media related to the Holocaust and encouraging them to reflect on the contemporary relevance.”

This article is part of our series on digital and media literacy education initiatives. Previous entries in the series include: PBS NewsHour Student Reporting Lab Program Ready to Expand and FTC’s Admongo Promotes Surface-Level Advertising Literacy.