Long before story sharing features emerged on Instagram and other popular platforms, advocacy organizations were pioneering a digital crowdsourcing strategy called “story banking.” Powered by digital technology that enables massive story collection and real-time story dissemination efforts, story banking ushers in the era of stories as data and political story on demand.

Among the myriad digital buttons that populate a given app or website asking users to donate, rate and contact is an emerging appeal to “Share Your Story.” While it’s difficult to pinpoint the exact origin of the story button, our research published recently in the Journal of Information Technology and Politics tells a tale not so much of Silicon Valley innovation, but rather of Beltway ingenuity.

Long before story sharing features emerged on Instagram and other popular platforms, advocacy organizations were pioneering a digital crowdsourcing strategy called “story banking.” Powered by digital technology that enables massive story collection and real-time story dissemination efforts, story banking ushers in the era of stories as data and political story on demand.

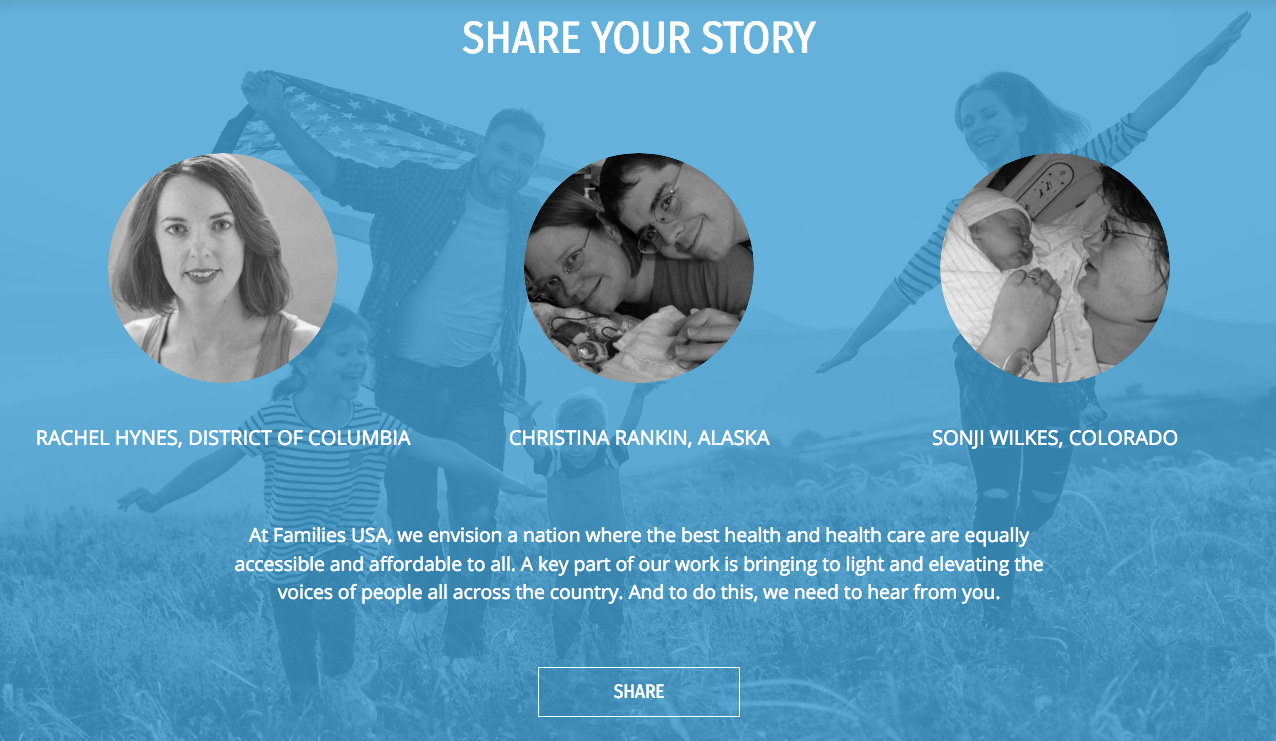

The healthcare advocacy organization, Families USA makes portions of their story bank accessible to visitors online. They also solicit story contributions through the same portal. The content available for public interaction is a selection curated from an underlying “bank” of personal narrative content that is refined over time and used across the organization’s communications.

Before platforms like Instagram and Facebook began soliciting “stories” through their interfaces, focusing instead (as they still mostly do) on raw content such as “posts,” “pictures” and “videos,” advocacy organizations like AARP and Families USA were pioneering a crowdsourcing strategy called “story banking” that specifically cultivates personal narratives for use in political communication. Powered by digital technology that enables massive story collection and real-time story dissemination efforts, story banking ushers in the era of stories as data and political story on demand, further changing the role of story in American culture. Our work examines the participatory potential of this technique and illuminates some important factors that currently constrain it.

A Google search for “share your story” turns up 73.7 million search results. Eight of the top ten results are advocacy organizations, including – in order of appearance – the March of Dimes, National Association of Mental Illness, One Love Foundation, American Heart Association, Save it Forward, Project Lead the Way, Women for One and UNICEF.

Our research shows that what began as a rudimentary email and spreadsheet scheme implemented by public-interest healthcare groups in the early 2010s was reinvented more broadly as a strategic response from progressives to Donald Trump’s far-right rhetorical strategies. Fighting viral fiction solely with hard facts failed progressives during the 2016 election. Truthful stories that could be generated like facts presented progressives an appealing strategy to defending their interests through popular support over the course of President Trump’s administration.

Unlike Families USA, the Center for American Progress provides a way for patrons to submit stories but no way to engage with the community of storytellers similarly contributing to the organization. Stories are framed more purely as critical resources to be donated. Notably the “share your story” link on CAP’s Action Fund website appears as a banner menu option, right next to the option to donate.

Not only did the idea catch on with groups like the Center for American Progress and Everytown for Gun Safety, but it has professionalized, leading a growing number of organizations to invest their own resources in story banking work in addition to raising grant money from philanthropies that have championed this technique over the past decade. Today, some of the county’s largest progressive organizations are integrating story banks with consumer analytics software such as Salesforce and harvesting personal narratives on an on-going basis. Many of them boast of story banks with tens of thousands of entries and constantly growing.

Stories are harvested with a logic of preparedness (being ready for the next battle) and reactiveness (responding to issues, but not leading debates). Initial submissions that typically come from the “Share Your Story” button mark the beginning of a development process that prepares stories for distribution to a range of publics through multiple channels. Importantly, the raw material constitutes a form of data that remains stored to serve some future value to the organization, including in projects that are not necessarily story related. Some story banks are shared among partner organizations, leading to new alliances or cementing and expanding existing ones.

Crowd-sourced personal stories are more than a persuasive gimmick because they can infuse key public debates with grassroots “expert” views via “embodied knowledge” derived from firsthand experience. With story banks, personal stories are systematically mobilized through news monitoring, algorithmic shortlisting, and audience testing to respond to breaking news and controversial statements, particularly by the Trump administration. This boosts the readiness of grassroots organizations and enables them to choose from a broader range of stories than ever before, potentially elevating new and previously unheard voices. Yet, this approach also limits story banking to being a reactive strategy, encouraging organizations to follow instead of leading public debates.

Another consideration is that black box algorithms capable of ranking content by relevance are essential to ensuring that story banking with tens of thousands of entries are usable. This is in addition to another set of external inputs including the government’s agenda and preferences of target audiences, which fundamentally contribute to determining which stories are used and which are not. Story bank administrators are acutely aware that this might lead to a divergence between how communities would like to be represented and how they are represented through story banks and are working to resolve this tension. This is a space to watch and one in which we are likely to see significant innovation in the future.

Bryan Bello is a CMSI research fellow and doctoral candidate in the School of Communication at American University.

Filippo Trevisan is a CMSI faculty fellow and assistant professor of public communication in the School of Communication at American University.

This blog post is based on their recent article with Michael Vaughan (Weizenbaum Institute) and Ariadne Vromen (University of Sydney): “Mobilizing Personal Narratives: The Rise of ‘Story Banking’ in U.S. Grassroots Advocacy,” published in the Journal of Information Technology and Politics in December 2019. If you have questions or wish to receive a pre-print open access copy of this article, get in touch with Filippo Trevisan at [email protected]