The Tribeca Film Festival 2019 featured an abundance of extraordinary documentaries, and of course the extraordinary subjects and directors who made them.

Stories for change

For me, some of the most exciting parts of the festival were meeting some of the extraordinary people in films that reveal the

As Slay the Dragon shows, activist Katie Fahey led a movement to make Michigan redistricting nonpartisan.

force of social movements. Some of the Parkland students were present for screenings of After Parkland, a smartly-executed film made by Nightline producers and journalists Emily Taguchi and Jake Lefferman. Barak Goodman and Chris Durrance’s handsome Slay the Dragon, a Participant Productions film, made gerrymandering into a gripping topic by focusing on two struggles. In Michigan, Katie Fahey led a successful citizen movement to create a nonpartisan, citizen-led redistricting process. Meanwhile, a husband-and-wife team of lawyers, Ruth Greenwood and Nick Stephanopoulos, participated in an effort to declare gerrymandering unconstitutional (Brett Kavanaugh’s appointment ended that). They and others were all there, still working; Fahey told me she has started a new citizen-led organization for change, thepeople.org.

For They Know Not What They Do tells the story of four families whose children’s gay or trans identity made them reconsider their attitudes toward gender in light of their other religious values. The four stories, each of them unforgettable, are interwoven expertly (direct Daniel Karslake tips his hat to his editor, Nancy Kennedy). “I decided to

Filmmaker Daniel Karslake

make the film when I noticed in 2015 I was getting death threats on the site of my earlier film, For the Bible Tells Me So,” Karslake said. “I wasn’t living in the U.S., and I thought, ‘What is going on in America?’ I felt it was urgently important to do this now. For me it’s about preventing suicide—so many LGBTQ people are at risk. Maybe if they see someone else’s parents coming around, it’ll give them hope.”

Yu Gu’s A Woman’s Work: The NFL’s Cheerleader Problem follows several women who have sued football teams and the NFL for fair working conditions. If you haven’t been following this sports story, NFL teams have been able to

Filmmaker Yu Gu

convince highly trained and talented women to cheer for pennies or even for free, and also to serve as stand-up sexual objects for fundraisers and VIP events. The women who spoke out have faced criticism from within cheerleading ranks as well as high-powered pushback from NFL and team lawyers. The film features two women with two very different, equally compelling stories, as they make the decision to fight for their rights.

“I don’t come from the dance or cheer world,” said Yu Gu, who was born in China and raised in Vancouver, CA. “I came to this project with an outsider perspective. You know, one of the mantras of filmmakers of color is, ‘Nothing about us without us.’ But here I was, making a film about a very white world. It took a long time to build trust.” She said that she found many links with her subjects, including “the value of hard work” and the power of community. She came to sympathize not only with the women who were heroically facing ostracism and being shut out of their chosen profession, but even the cheerleaders who opposed them. “For so many generations, women have not been afforded the opportunity to have a sisterhood, a community.

The NFL and teams recognized women wanted and craved that, and sold the dream to them.”

“I always thought I was trying to be a role model as a cheerleader,” Lacy Thibodeaux-Fields, the original plaintiff in the first lawsuit, told me. “But in this work, I think I’m being a more important role model.” The Independent Television Service-funded film should end up on public TV.

Independent visions.

There were also some wonderful examples of independent longform work in a distinctive voice. Martha Shane and Ian Cheney’s Picture Character, for instance, is both quirky and compelling. It tells the history of emoji and emoji language (yes) while following several people who follow the approved process to get a new emoji into the Unicode set. Will the committee approve a hijab emoji? an emoji for the popular Argentine drink mate? an emoji for women’s periods? The suspense builds. Were you too wanting a women’s shoe that’s not high-heeled, or a sewing machine? Even as the committee work grinds on, people are busy turning pictures into language, as if the Egyptians, the Chinese and Blissymbolics hadn’t already done that, and seemingly innocuous strings of emojis form sentences you might want to think twice before hitting send on.

Two films introduce us to different aspects of the large and growing Chinese middle class that many documentaries and virtually all news reporting miss. Shosh Shlam and Hilla Medalia’s Leftover Women is a warmly intimate portrait of several Chinese women who, in their late 20s, are stigmatized as “leftover” by the Chinese government for failing to be married. (China’s one-child policy resulted in a demographic imbalance; this is the government trying to help out the guys by shaming holdouts.)

Yang Sun’s Our Time Machine is a treasure of a cross-cultural experience. It features Maleonn, a celebrated artist in the

Artist Maleonn creates a puppet play about memory and loss in Our Time Machine

Chinese art world who makes elaborate, life-sized puppets. He’s staging a complex play about memory, to honor his theater director father as the dad slips into Alzheimer’s. While in the play, the hero creates a time machine to rescue his father, in real life the father slips ever further into dementia. Yang Sun’s ability to capture the theatrical wonder of Maleonn’s work helps introduce this extraordinary artist to the West. And of course, the story of loss and the next generation rising is universal. The message of the film is simple, said the director; “there is no time machine.” Producer S. Leo Chiang said that this will probably be the rare film that is distributed and broadcast in both China and the U.S. Since this is an Independent Television Service funded film, look for it on public TV sometime in the next year or so. But if it comes to a theater before then, run to get your ticket.

Closely observed.

Cinéma vérité films showed the power of intimate access over years, and push us beyond clichés about poverty in developed countries. They are both set in post-apocalyptic landscapes of late capitalism, in the leftover urban areas abandoned by manufacturing. Scheme Birds started when Ellen Fiske and Ellinor Hallin, two Swedish filmmakers, met a magnetic personality–15-year-old Gemma while spending time in Scottish public housing (or “scheme”) in a rustbowl town. They followed her for years, as she worked with her caring dad—who like many there raises pigeons, partied, had a baby, lost friends, and made the big decision to make her child her focus. Their deeply respectful and compassionate film makes no excuses and doesn’t need to, because it’s inside the lives of its characters. You can’t stop watching.

Scheme Birds won Best Documentary at Tribeca. The jury noted that it won for “its poetic, haunting depiction of compelling characters living on the edge. Every element of the film, from editing to cinematography to point of view, is superb. The filmmakers convey their voice in a unique and present-tense way.” It also won the Albert Maysles New Documentary Director Award, “for a film that tells a deeply compelling story, but realised with cinematic vision and invited us intimately into the lives of the film’s characters.”

17 Blocks is Davy Rothbart’s “adopted” family’s story. He grew up in a beat-up part of Washington, D.C., near an African-American

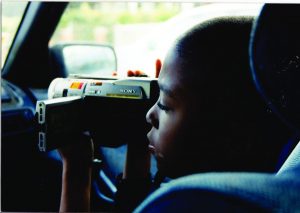

Nine-year-old Emmanuel Durant focuses his first camera.

family that embraced him. When he let the nine-year-old, Emmanuel, start playing with his camera and eventually gave him a camera of his own, a decade of filming began. And when Emmanuel, a good student who avoided drugs, was shot to death at 19 by an enemy of his drug-dealing older brother, the family turned to Davy to continue recording the story. This look inside a family navigating through bleak landscapes and bleaker opportunities, patching over spectacular potholes of inequality with enormous amounts of love, is another testament to the daily heroism required for poor people to survive their lives.

17 Blocks won the Best Editing in a Documentary award, “for its profound treatment of vast amounts of honest, often raw footage. The film is structured in a way that renders some of the most affecting moments with great subtlety. Viewers are transformed over the course of the film, a testament to the choices made in its making.”

Finally, Jeanie Finlay’s Seahorse, a BFI/BBC Storyville production, carries us into pioneering territory in terms of gender. Freddie, a gay transgender man who wants a family, decides to carry a baby—“it’s the cheapest and simplest solution,” he thinks. Why not just use his “hardware”? But as we follow the pregnancy, he and we see that it’s anything but simple. I found myself in uncharted emotional territory watching the film. And I was awed as much by Freddie’s bravery in allowing the filmmakers into his life as I was by the soup-to-nuts national health care he experienced and the extraordinary support of his family.