Roger C. Memos.

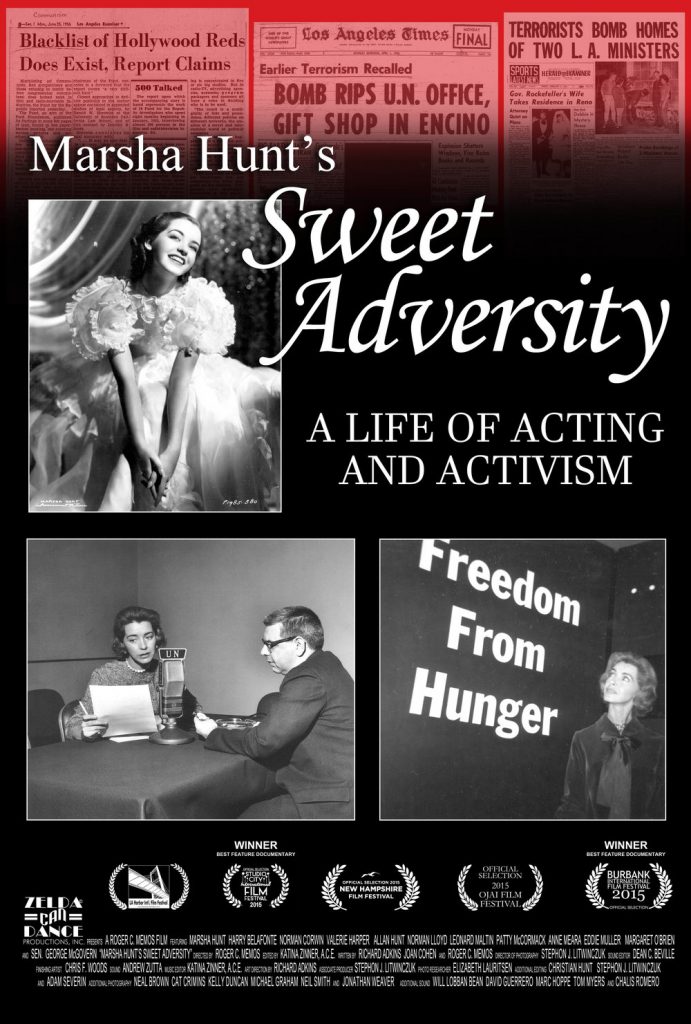

Roger C. Memos is no newcomer to the world of copyright. With 20 years of experience in the film and television industry under his belt, Memos has worked rights and clearances for a myriad of daytime and primetime television shows, from the early days of Entertainment Tonight to the recent CNN documentary series The Seventies. A few years ago, however, he embarked on a new journey: directing and producing his own feature-length documentary. The film, Marsha Hunt’s Sweet Adversity, follows Hollywood starlet Marsha Hunt from the beginning of her career at age 17 in 1935, through Hollywood’s blacklist of her in the 1950’s, to her eventual re-emergence as the original “celebrity activist.” Considering that Hunt starred in over 100 films and television programs throughout her career (many of which were integral to the story of the documentary), Memos quickly realized that two words would soon become his best friends: fair use.

“I could not have told her story without fair use,” he stated unequivocally. “I literally couldn’t do it because the studios would step all over me and stop me, not only because of the cost, but also because of the rights that they would not allow me to have.”

“The Paramount years – which is now owned by Universal – they’re not prohibitively expensive if I had to license clips. They actually have 15-second rates. But MGM clips from the war years, ‘39-‘46 – Warner Brothers is very restrictive. The rights are very restrictive.”

In the end, Memos was able to fair-use all of the motion picture clips in the film (those that weren’t already in the public domain), in addition to a number of photos and other film clips. Initially, he says that the film team was lucky in getting access to the material—fair use only is available to a creator if they can get access to a work without going to a licensor. Hunt herself had a stockpile of old photos from her career, but they still had to search outside Marsha’s house for additional material. When deciding whether or not something would be covered under fair use, Memos says that he just kept one thing in mind:“Criticism and commentary – it’s that simple.” (Although criticism and commentary are only two of many possibilities for a use to be transformative, and therefore eligible to be fair use, they were Memos’ primary reasons.)

Marsha Hunt in “Cry Havoc.”

“As she described her experiences, I felt confident that we could use the photos,” he explained. “Whenever she would reference a director or reference a fellow actor, or when she was talking about the war. I showed a clip of the John Birch society and then Marsha said something like ‘I don’t know who the John Birch people were, but they were full of hate.’” Memos was illustrating Marsha’s comments, using images to remind viewers of what she was talking about. This kind of use aligns with the second category in the Documentary Filmmakers Statement of Best Practices in Fair Use.

Memos didn’t find it restrictive to work around the rules of fair use when inserting clips, but he does admit that occasionally “with motion picture clips, you definitely had to tweak the story and the editing in order to make the clip work.” For example, his plan to open the film with a montage of film clips proved slightly difficult, as there was no direct commentary.

“Originally, I had learned that you couldn’t really open the film with a montage – unless you maybe had a chyron that said ‘Marsha was a busy actress’ or something and then showed some clips.” This once-common adage has, since 2005, been entirely reversed in practice, as filmmakers have come to understand how to apply fair use. These days, beginning montages and montages throughout work routinely employ extensive fair use.

Memos decided, however, that he would public domain clips for the opening montage, then transitioning into fair use clips after that point.

Get In, Get Out

There’s one other fair use motto that Roger Memos goes by: “Get in, get out and make your point.”

“I was very judicious in the amount I used throughout the whole process,” he said, “just trying to remember ‘get in and get out’ so that it would bolster my case.”

As the Documentary Filmmakers’ Statement of Best Practices in Fair Use states, fair usage must be in an amount “taken appropriate in light of the nature of the copyrighted work and of the use.” Memos feared that he may be stretching that “appropriate amount” to its limits with one clip – an interview clip which lasted nearly 18 seconds.

“I thought ‘well, this’ll be a real test’ because you’re supposed to get in and out,” Memos said. As it turned out, he had no reason to worry. The entire clip was deemed fair use as it was necessary to the story of the film. That is because there is no fixed limit for how much is enough; you use what is reasonable for you to accomplish the transformative purpose.

Marsha Hunt’s Sweet Adversity (2015)

Fair Use as a Bargaining Chip

While working on another project, Memos learned another utility of fair use: as a negotiation point. Called in to advise on clearance for the PBS documentary John Lewis: Get In The Way, he was faced with a challenge. After having screened at film festivals, the film was on its way to PBS. However, several images that had been fair-used in the theatrical screenings were low-resolution and PBS wanted to replace them with high-resolution versions by licensing from Getty Images and other vendors. His attorney’s advice? Use fair use to try to cut a better deal. Seeing as they’d already fairly used the images in the film festival run, the filmmakers hoped that the copyright owners might be more open to reducing the price of the high-resolution versions.

“We wanted to make sure the photos looked the best they could for distribution on PBS,” Memos said. “So I was hoping that the licensor would give us the best price they could as we had a restricted budget.”

“And it worked.”

Getty and the other vendors reduced their prices to accommodate the budget of the film, and it aired nationally on PBS with the high-resolution photos in February 2017.

The Copyright Culture

Memos highly values the community he has built up over the years. Between his industry work and organizations like Clear (a professional organization to which he belongs where research and clearance professionals host seminars on various topics including fair use), he has a wealth of experts in various fields on which he can call if he needs help on a claim.

“We all kind of lean on each other – sometimes you think you know what you’re doing, and you’ve been doing it a long time, but the genres blend sometimes. You don’t know if it’s entertainment or news, or does this apply? Can I do this?”

“In a way, you have to be kind of humble and say “I’m not sure of myself, what do you think?””

Memos says that he is just grateful that fair use allowed him to bring Marsha Hunt’s story to the screen. He looks forward to a wider embrace of fair use, a shift in perspective that could view it as a boon to creativity rather than as a fallback.

“I think it should be the first avenue to pursue. I just know from my own experience – I could not tell Marsha Hunt’s story without fair use being the law of the land, a viable option if you’re following the rules.

“I’m grateful because it gave me an opportunity to tell my story.”