Filmmaker Lyn Goldfarb.

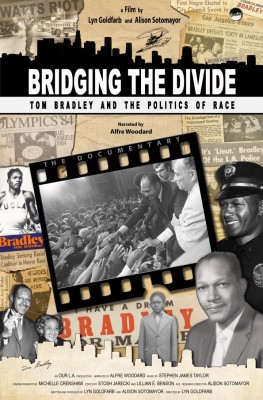

When filmmaker Lyn Goldfarb began her career in the late 1970’s, fair use was far from a consideration for documentarians. The 1976 Copyright Act had just, for the most part, reaffirmed and strengthened the tenets of long and strong copyright, expanding ownership and increasing penalties for infringement. Even if she had wanted to fair-use clips, the trouble that it would take to find high-quality footage in a pre-VCR (not to mention pre-internet) world was practically cost-prohibitive in and of itself. Thirty years, 2 Emmys and an Academy Award nomination later, the veteran filmmaker found herself in new territory when she realized that her latest film, Bridging the Divide: Tom Bradley and the Politics of Race could benefit from what fair use had to offer.

Staying Organized

The film, directed by Goldfarb and produced with Alison Sotomayor, chronicles the career of Tom Bradley, the first and only African-American mayor of Los Angeles who held the office for a record 20 years. Spanning a swath of L.A.’s history bookended by the Watts Riots in 1965 and the Rodney King Riots in 1992, the film relies heavily on historical photos, newspapers and archival footage to tell Bradley’s story. For the 57-minute doc, the filmmakers fairly used almost 100 photos, video clips and newspaper headlines, and they wanted to make sure that they had an ironclad defense for each of them. The key to a good defense, according to the film’s research director Alison Sotomayor, is organization.

“We had one of those big, thick, like four-inch binders – we may have had two of them – full of material, so we really backed up everything because we wanted it to go as smoothly as possible,” Goldfarb explained. “So when we submitted it for review, they could look at every instance and they could see the backup of why we thought it was fair use.”

“We were both very confident because we had really researched it ourselves. We didn’t want to pay the lawyers for things we could do ourselves.”

The meticulous documentation lowered their legal costs. When it came time to contact their lawyer for errors & omissions insurance, only one of their claims was refused – a decision which the filmmakers, upon further review, agreed with. And not only that, some of their deposit was returned, because the legal work could be done so efficiently.

“We got almost half of our deposit back, because we didn’t spend as much as they thought. And that’s because we were so well-organized with it.”

The photo that was rejected was to be used in the ending credits sequence, but was not necessary to telling the story. The lack of a transformative aspect to their use of the photo made it unlikely that they would be covered by fair use.

“The moment they said it, we went ‘oh yeah, of course, it doesn’t work for fair use,’” Goldfarb laughed, “but we’d kind of forgotten as we were putting it together.”

Orphans in the Divide

For the team working on Bridging the Divide, one of the most useful aspects of fair use proved to be its coverage of orphan works: that is, material where the author is either unknown or unreachable. Fair use applies to all copyrighted material alike, whether the copyright holder is known or not. Because Bradley’s long career stretched back to the mid-60’s, they found themselves in possession of a number of photos for which it would have been difficult to obtain licenses.

“There were a lot of photos that were taken while he was in office that had no label on the back,” Goldfarb said. “We didn’t really know where they came from.” She added that several of the newspapers from which they had used headlines were no longer in existence, so they could not have licensed them even if they had wanted to. Fair use’s coverage of orphan works, therefore, was an invaluable protection that allowed them to use many photos and newspaper headlines that they would otherwise have been prohibited from using.

“You make at least three attempts by letter or email or calling, and if you really can’t reach someone, then you don’t have to clear it.”

“We did multiple tries, so we knew we were safe in that.”

Balancing Act

While Goldfarb was quick to embrace the utility of fair use, she says that transitioning from a licensing mindset to a fair use mindset didn’t come without its complications. She worried about disturbing business relationships. After thirty years in the industry, Lyn and Alison had established good relationships with archives and other copyright owners: relationships that they were reticent to jeopardize. This led to several instances where the filmmakers decided not to fair-use clips even though they clearly would have been covered.

“Alison had established really good relationships with archives…and we actually didn’t want to fair use things where we had good strong relationships – where people were really searching for things with us and we were generally getting really good rates on it…we wanted to maintain those relationships.”

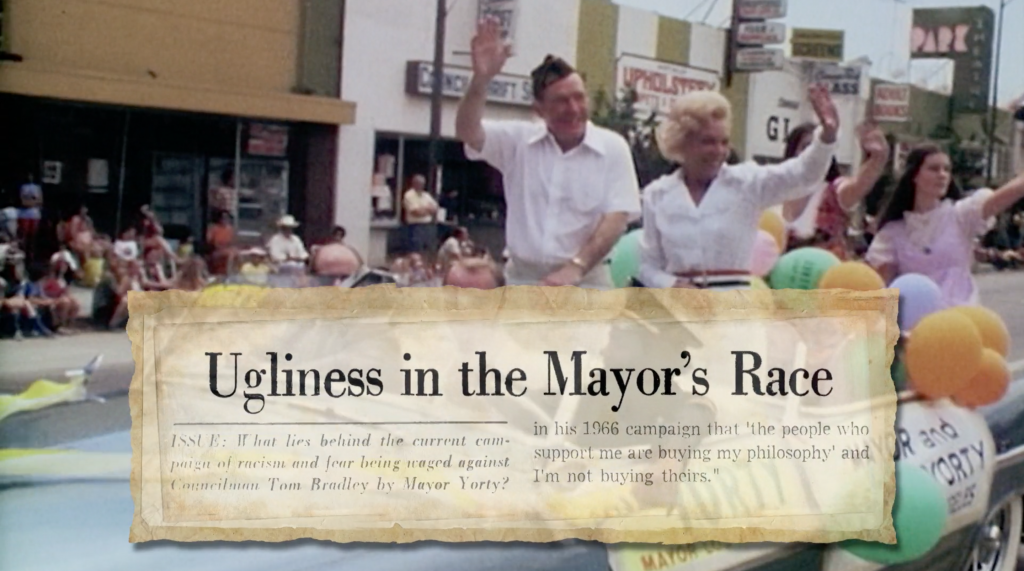

Still image from Bridging The Divide (2015).

Goldfarb describes their decision-making process as a kind of balancing act between several different factors: maintaining relationships with archives, making sure that she was getting the best quality footage possible, and weighing licensing fees against lawyer’s fees.

“Sometimes, it’s not worth the lawyers’ fees. It really depends on how much you have to spend versus how much you have to spend to license it.”

In the circumstance of licensing footage of Rodney King’s beating, several of those factors came into play and ultimately led the filmmakers to decide to license the footage, despite the fact that they could easily have fair-used it. They even already had a copy of the footage after having licensed it from George Holliday for a prior film. That previous license, however, proved to be a complicating factor.

“The license that we had said that it was only to be used on that film, The New Los Angeles, so when we wanted to use it again… we knew we had to pay him again because we’d signed an agreement. Now, had we started out in the beginning or started out years later, we probably could have fair-used it – a lot of people fair-use that footage. But then again, we felt okay respecting the ownership of the footage.”

Embracing Fair Use

Beyond the King footage, Goldfarb recognizes other times when fair use could have come to her aid on previous projects. Years ago, she went through a tiresome runaround attempting to license several photos of the Olympics, but the Olympics refused to license to them.

“Had fair use been industry practice then – it was prior to the point of fair use being used commonly– we would not have had a problem using it because the stills we were interested in were absolutely essential to the storytelling.”

Indeed, the creation of the Documentary Filmmakers Statement of Best Practices in Fair Use both publicized the utility of the doctrine and also made it easier for documentarians to understand how to apply it. The result within a year was change in insurance practices, which also led to broadcaster acceptance and change in filmmakers’ choices.

When it came time to find footage for Bridging the Divide of the 1984 Los Angeles Olympics (one of Tom Bradley’s crowning achievements as mayor), Goldfarb and Sotomayor attacked the problem with a new confidence in their rights as a content creator. In the end, they successfully fair-used 100 percent of the Olympics footage used in the film. Goldfarb attributes this confidence in fair use to good organization and good research.

“It was being aware, from the early stage, of what to do and what not to do, which enabled us to really be able to utilize fair use,” she elaborated. “Going to workshops, listening to speakers…certainly getting the first publications [Codes of Best Practices] on fair use– but for me as a filmmaker, it was the reinforcement through workshops and seminars that made me feel somewhat comfortable.”

“That was important because we didn’t want to have to pay for lawyers until we absolutely needed them, so it was familiarizing myself enough so that we knew what we were doing.”