Jed Riffe

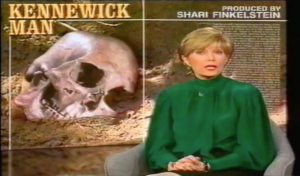

In 2000, documentary filmmaker Jed Riffe faced a conundrum. He was finishing up post-production on his film Who Owns The Past? and wanted to open the film with 30 seconds of footage from CBS’ 60 Minutes. The film focused on the controversy surrounding the Kennewick Man, a 9,000 year old Native American skeleton whose discovery ignited a battle between anthropologists and Native Americans over ownership of the remains. What better way to introduce viewers to the depth of the controversy, Riffe figured, than by showing the media coverage from a national television program? There was only one problem: 60 Minutes wasn’t selling.

“You couldn’t buy it,” Riffe explained, “so they didn’t want anybody to use it.”

In order to get a national broadcast, the film would need errors & omissions insurance, which would require securing the rights to every second of footage in the film. So Riffe had a decision to make. He could either scrap the sequence and re-edit the opening of his film (thereby curbing his vision for the project) or he could try to acquire the rights to the footage through another means: Fair use.

Riffe was apprehensive, never having explored Fair Use. He got in touch , who agreed to take a look at the film.

“He wrote a letter,” Riffe recalled. “He said I used as much as I needed, and no more, to make the point. I got an E&O, I got a national broadcast.”

The film, complete with 60 Minutes footage, aired nationally on PBS and went on to win a Bronze Award at the Worldfest Houston International Film Festival.

Fair use: From exception to the rule

Riffe was lucky in 2000. He knew a lawyer well-versed in fair use (still not that easy to find), and he found an insurer who was willing to make an exception to the routine practice of carving out fair uses from insurance. It may have helped that his lawyer was also George Lucas’ lawyer.

But since 2005, you don’t have to be lucky or well connected to employ fair use. Documentary filmmakers got together in 2005, with the help of CMSI’s Patricia Aufderheide and Prof. Peter Jaszi from the Washington College of Law, to create the Documentary Filmmakers’ Statement of Best Practices in Fair Use. That simple document created a common understanding, not only among filmmakers but also insurers and broadcasters, over how to interpret fair use. And that drastically lowered the risk involved in making a fair use decision. Today, insurers routinely accept fair use claims within the normal fees for errors and omissions. Filmmakers report that broadcasters accept their work with fair use claims.

In the intervening years, Riffe has also grown more comfortable with his creative rights concerning fair use. Over his career, he has produced nearly a dozen documentaries and television specials, of which nine were nationally broadcast and one was released theatrically – but it has only been in the past decade, he says, that he feels he has truly been able to take advantage of fair use. He credits his change in attitude to a combination of factors. The release of CMSI’s Codes of Best Practices, including the Documentary Filmmakers Statement, has given him confidence in the breadth of fair use.

His understanding of fair use then made it possible for him to wisely use the resources burgeoning on the internet. The rise of YouTube led to easy access to a wealth of footage that previously was hard to come by. Riffe says that sites like YouTube and Archive.org, a non-profit website containing millions of free films, audio recordings, books and music, have “amazingly changed the playing field” for himself and other filmmakers. “We’ll find a high resolution version on YouTube,” he said. “That wasn’t possible for me in 2005.”

DVR technology, he says, has also given documentary filmmakers greater independent access to material.

“I bought footage from BBC – and I had better footage on my TiVO. And I used it! And that moment is when I began to go ‘why am I buying this, when they don’t even give me as good a quality as what I can now tape?’”

Why fair use?

Riffe sees fair use as particularly useful given exorbitant license fees charged by many copyright owners. 60 Minutes, for example, has since begun selling their footage – but at a pricey $150 per second. That would be nearly $5,000 for the 30 second clip in Who Owns The Past?, an unfeasible amount for an independent documentary film. (Other filmmakers have discovered that fair use can help in negotiations; letting a license-holder know that you can design your project in order to fairly use their material can help them get to a more reasonable price.) When he licenses his own material, he doesn’t forget. “I charge one price to independent filmmakers that’s extremely low. And then those people that charged me $150 [per second] – they pay twice as much.”

60 Minutes footage from Who Owns the Past? (2000)

Fair use is also useful in situations where a rightsholder doesn’t reply, can’t be found, or chooses not to license material. For all such uses of this newly available material, of course, Riffe needs to understand his fair use rights, unless he intends to license it. To do that, he can turn to the Documentary Filmmakers Statement, or to an increasing number of lawyers who have also read it. And he does have to get a lawyer’s letter agreeing with his own fair use decision, in order to get E&O.

In some cases, for instance finding background music, another option to avoid standard licensing, which he and his team also use, is to search for material that employs a Creative Commons license, which provides blanket permission for certain kinds of uses.

In all his years of utilizing fair use, Riffe has never had a fair use claim challenged. He had a brief exchange with new management at the Heart Museum, which claimed copyright on photographs used in Riffe’s film Ishi: The Last Yahi, but the photographs all fell firmly within the public domain (all were taken between 1911 and 1916) and so there was no need to invoke fair use.

Easier licensing?

But Riffe doesn’t always employ fair use; he also licenses where it is easy and appropriate. As a media creator, he sees both sides. “I sell a lot of footage,” he said.“So I’m very interested in protecting that, but at the same time, I can understand how people can use certain materials . There are going to be times where people will fair-use my material, and I have to live with that.” He understands that fair use is available for everyone, and also that it is limited, and that there may be other reasons to license it even when you don’t have to.

He hopes that pricing can become more appropriate to the uses. If the price were more reasonable, he believes that he and other filmmakers would be much more amenable to buying footage outright rather than pursuing fair use, since fair use is not without its own costs. It could be cheaper and easier to simply buy the footage than to document justifications for fair use and paying for a lawyer’s letter; sometimes you want the quality an archive has; and sometimes you simply want to maintain a relationship.

Fair use for our heritage

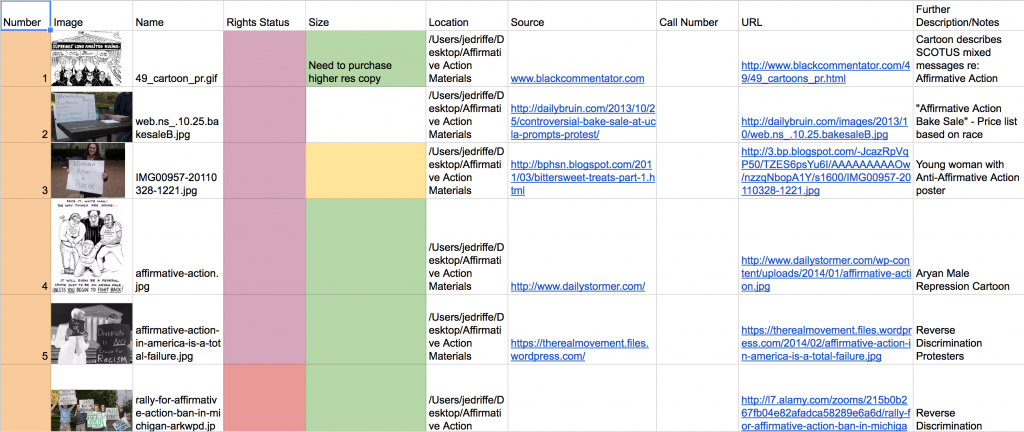

Excerpt from Jed Riffe’s copyright database

Riffe is currently working on a documentary focusing on African history and the African-American experience, an outgrowth of an interactive multimedia experience he developed several years ago for Merritt College. Along with Dr. Siri Brown in 2014, Riffe and his team designed the Africana Interactive Studies Center, which features nearly 10 hours of content for students to peruse – all of it justified through fair use. (Consult the Code of Best Practices in Fair Use for the Visual Arts and the Statement of Best Practices in Fair Use for Orphan Works to see best practices in online collections.) Their original budget for archival footage maxed out at $5,000 – roughly the equivalent to the cost of 30 seconds of 60 Minutes footage. Armed with the knowledge of fair use, Riffe’s team created an extensive online spreadsheet cataloging every clip and image, along with its source and rights status. Now in production for his film The Long Shadow on the same topic, he has access to a wealth of content right off the bat. Meanwhile, the Africana Center at Merritt continues to draw crowds of students, its treasure trove of content consistently proving to be one of the most popular resources for African Studies students. Riffe holds this project up as a prime example of the need for fair use:

“This is our history. This is our heritage. It’s everybody’s. It belongs to all of us. And for educational purposes, it should be available. That’s where fair use works.”