At last month’s College Art Association annual conference, panelists showcased how much visual arts professionals’ practice has changed since the creation of the Code of Best Practices in Fair Use for the Visual Arts.

At last month’s College Art Association annual conference, panelists showcased how much visual arts professionals’ practice has changed since the creation of the Code of Best Practices in Fair Use for the Visual Arts.

An ongoing survey is assessing trends in the field. While many visual artists (you, perhaps or a friend) still need to take it, CMSI Senior Research Fellow Patricia Aufderheide and CMSI graduate fellow Donte Newman found preliminary evidence that visual arts professionals are using fair use more than last year, to:

At the annual conference, Anne Collins Goodyear, co-director of the Bowdoin College Museum of Art and CAA president emerita during whose tenure CAA created the Code, opened the panel of fair users in the visual arts.

Carole Ann Fabian, the Director of the Avery Architectural and Fine Arts Library at Columbia University, reported that Columbia advances the principle of open access policy where possible, and that Avery librarians draw upon three fair use codes when advising library users about quoting from or reproducing copyrighted materials: the Code of Best Practices in Fair Use for Academic and Research Libraries developed by the Association of Research Libraries (2012), CAA’s Code of Best Practices (2015), and the Association of Art Museum Directors (AAMD) Guidelines (2016). The shared norms of the CAA and AAMD codes, both of which champion a liberal assertion of fair use, provide particularly helpful guidance on fair use applications related to copyrighted images.

Carole Ann Fabian, the Director of the Avery Architectural and Fine Arts Library at Columbia University, reported that Columbia advances the principle of open access policy where possible, and that Avery librarians draw upon three fair use codes when advising library users about quoting from or reproducing copyrighted materials: the Code of Best Practices in Fair Use for Academic and Research Libraries developed by the Association of Research Libraries (2012), CAA’s Code of Best Practices (2015), and the Association of Art Museum Directors (AAMD) Guidelines (2016). The shared norms of the CAA and AAMD codes, both of which champion a liberal assertion of fair use, provide particularly helpful guidance on fair use applications related to copyrighted images.

Avery is often the first point of contact for students and faculty who have questions about these issues, and her organization, along with its digital surrogates, is also a provider of primary content to scholars worldwide. Having a concise resource like CAA’s Code makes it infinitely easier to introduce library users to this essential feature of American copyright law.

Victoria Hindley, Associate Acquisitions Editor, MIT Press, reported that discussions about fair use at last year’s CAA Annual Conference motivated her to work with her colleagues at MIT Press to pursue a fair use initiative of their own. With support from Executive Editor Roger Conover, Press Director Amy Brand, legal counsel, and others, Hindley helped to define a progressive position in support of responsible fair use.

“One of our primary goals,” she said, “was to figure out how to reduce the burden of clearing permissions placed on the author.” The resulting proposal, which is undergoing final Institute approval, is a robust document that most notably, as she explained,

“would no longer require authors to indemnify the press when they have made a reasonable good faith determination of fair use.”

MIT Press has developed newly proposed contract language in support of this position; and, to further empower artists, the Press has crafted permissions guidelines that take advantage of the CAA Code and also refer authors to it. “The CAA Code of Best Practices has proven to be an invaluable guide for us as we’ve held these discussions and made decisions about our own guidelines,” noted Hindley. The new policy pending adoption at MIT Press would provide protections similar to those that CAA grants contributors to its publications.

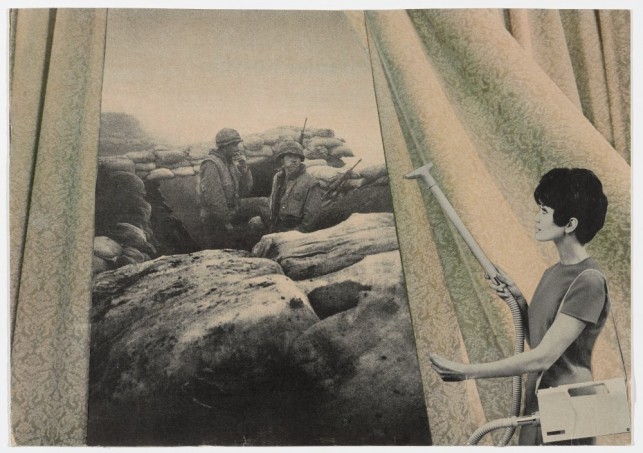

“Cleaning The Drapes.” Martha Rosler.

Artist Martha Rosler, who received a Lifetime Achievement Award during the conference from the Women’s Caucus for Art, has for decades incorporated into her work images circulating in what she has called the public sphere of mass media, including newspapers, magazines, and television, effectively employing fair use. While showing examples of her work, Rosler described the importance of processes like hers, which, she said, for many artists “constitute an essential form of critique.”

Rosler noted that the Code has the potential to offer support and encouragement to other artists who might otherwise shy away from the legitimate use of copyrighted material in their work. She also observed, with regret, that many artists, particularly those working in video, have deliberately abandoned or failed to undertake projects involving appropriation precisely because the legal departments of broadcast entities have in the past barred airing of works employing fair use. (With the broad acceptance of codes such as the Documentary Filmmakers’ Statement of Best Practices in Fair Use, broadcast positions have changed, but often errors and omissions insurance is required, involving a lawyer’s letter verifying that fair uses fall within best practices.)

Francine Snyder, Director of Archives and Scholarship at the Robert Rauschenberg Foundation, talked about the positive effect on the Foundation of a proactive fair use policy in the year since it was introduced. The policy is intended to stimulate research and knowledge about Rauschenberg. Snyder reported that it has indeed done so already — for instance, with an online gallery for children that includes images of Rauschenberg’s work. The new policy has reduced scholarly anxiety. If you want to put Rauschenberg’s work on a mug or T-shirt, you will of course be licensing the work.

Do you have a story of how fair use works in your visual arts practice? Feel free to share at [email protected]. Also, take the survey here.