Night School tells untold stories that illuminate structural issues.

What’s the difference between a person and a problem? Several of the documentaries shown at Tribeca Film Festival showed us, taking up issues and taking us into the human drama behind him.

W.E.B. DuBois famously asked, rhetorically, what it was like to be a problem. He wanted personhood for the recently “freed” but savagely disenfranchised African-Americans. He wanted the capacity to be the subject of your own story, and to be given respect for having it.

The films that did this largely drew on the resources of the mature and endlessly inventive cinéma vérité form, following their subjects through lives constantly menaced by the objectifying forces of racism, poverty, and gender inequity.

Living through drama.

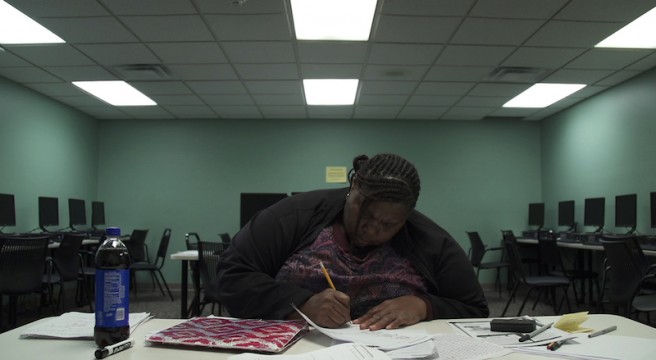

Night School, by Andrew Cohn (his Medora made the abandonment of many small towns across rural America vitally real), takes us inside the challenge of trying to get your education if you missed out on that high school diploma. In Indianapolis, where dropout and unemployment rates are sky high, three people are going to a program that’s regarded as wildly innovative. It’s not just a GED, which has no real clout in a job market that excludes dropouts from 90 percent of jobs. Instead, it teaches them the courses they missed, so they can get a real high school diploma. Night schools used to dot the landscape, and many immigrants got their bootstrap there. That this is such an exception is evidence of one way the educational system contributes to structural inequality. That this night school needs to offer its students so much support is a hint at how massively unemployment, lack of transportation, lack of childcare, laws that penalize ex-prisoners—not to mention pervasive discrimination–weigh against the goals.

The three people you meet—52 year old grandmother Melissa, who wants to prove to herself she can be somebody; Greg, a single dad who’s getting out of drug dealing and wants a real job; and Shynika, who’s fed up with fast-food work and dreams of nursing—are all people who look like the folks you may not even see on your commute on public transportation. Their stories are complex and all their own. The problems they face are structural, endemic, and belong to everybody.

The way their stories intersect with the problems they face is heartbreaking, but equally remarkable is the tenacity and spirit that keeps them going. It’s a real lift when Melissa gets a boyfriend, and Greg walks away from trouble brewing in his family, and Shynika decides to work with Fight for 15 (the minimum wage demand). Their choices aren’t always perfect for their goals. But it really shouldn’t be that hard for them to get an education, or need that much spirit, gumption and good luck. We also meet some people who don’t make it through the program, and it’s really not surprising.

Clearly, there’s mutual respect between the three African-American central characters and the white filmmaker, which allows the empathy to communicate off the screen. By the end, they have spent years together. Night School is anything but preachy. But these people have a lot to tell us, and it goes far beyond Indianapolis.

Close listening.

Tracy Droz Tragos’s Abortion: Stories Women Tell (soon on HBO) is a great example of close listening. Tragos listened to many women in and around an abortion center in the heartland (Missouri, where she’s from). This is not the drama of the woman at the moment of decision, but reflection on experience that may be yesterday or 20 years ago. The stories she heard are wide ranging, and defy a stereotype. Women got abortions to be able to finish school, to be able to take care of the kids they already had, to exit an abusive relationship. Regret isn’t much on display; generally people were comfortable with a choice they saw as responsible. One Christian woman and her husband prayed with their pastor before terminating an unviable fetus; she talks about the cruelty of facing clinic protesters as she grieved her desperately wanted child. Two women who carried their babies to term after considering abortion were deeply regretful; in one case, it destroyed a couple’s future, in another, the chance for an education. Escorts and security guards at the clinic have had abortions, a decision they are proud of having made, in the interests of all concerned. Anti-abortion protesters, however, include a woman who is deeply sorrowful at her choice for an abortion and a woman who mourns her lost child.

This is a film that shifts the conversation, allowing voice to people who have had plenty of time to consider their actions. The film is uncommented, but the stories speak loudly about the fact that many women see this decision within a context of their many other responsibilities, unenviable but not in the least haunting—indeed, the best outcome under the circumstances. The strength of the film is letting them tell us that.

Messy like reality.

Dana Flor and Toby Oppenheimer’s Check It is a little rough around the edges, like its subjects. But it’s messy like reality is. The Check It gang—well, that’s the police term, they call themselves family—is an LGBTQ group of some 200 people on the tough streets of Washington, D.C. The group has shocked other street groups with its violence—they see it as self-defense—and its open flaunting of transgender and gay identity. The film features a moment when a fashion designer includes them in a fashion show, hooking them up to major designers during Fashion Week. The effort runs up against the realities of life on the street and the social mores that make it possible to survive there; the film leaves us mid-drama. I was fascinated by the endless inventiveness of self-presentation, the bravado neatly matched with the insecurity, and the lack of support for these people, often children, whose differences have thrown them onto the street. The film illuminates a culture in formation, born of terrible and cruel hardship, sustained and also confined by community. It’s another piece of point-of-view reality that changes our understanding of what we see.