The annual parade, “March March,” at True False Film Festival.

On the verge of the Great Shutdown, this year’s True/False Film Festival fought off COVID-19 with gallon jugs of hand sanitizer, outrageous costumes, and endless cocktails of creativity.

Tucked into improbable venues throughout the college town of Columbia, MO, the festival showcases a wide range of documentary styles. It also attracts visual and musical artists throughout the Midwest, who showcase their art at the fest’s many venues. Now in its second year of post-founder operations, the festival’s theme was “Foresight,” a capacious umbrella for a host of issues and approaches.

Launched in 2003, True/False has a well-earned reputation as a filmmaker’s festival, an intimate place where your work and you are appreciated. It’s famous for its audiences, filled with thoughtful local people who love documentaries and the conundrums that come with them. They pack houses even at 9:30am on a Sunday, line the streets for the annual True/False parade, and stick around for later-night events like “Campfire Stories,” where filmmakers gather to tell tales (in this case accompanied by upright bass and Bulleit bourbon). Although it’s grown dramatically in recent years, festival hasn’t lost that homegrown feel.

Post-Sundance, Pre-Streaming.

If you don’t care about being the first to see a film, then using True/False to catch up on Sundance hits is a great idea—it’s a much more civilized environment for viewing. Kirsten Johnson’s Dick Johnson Is Dead, her touching and wryly funny project to come to terms with her father’s Alzheimer’s diagnosis, kept audiences laughing until they cried, and then laughed again. Time, Garrett Bradley’s narrative of one woman’s 18-year struggle to raise a family and get her husband’s lifetime prison sentence reduced, raised larger questions for audiences about prison reform and “the new Jim Crow.” Jim

Crip Camp, about the birth of a disability rights movement, energized True/False audiences.

LeBrecht and Nicole Newnham’s Crip Camp (an IDA Pare Lorentz Fund grantee) brought out a fleet of enthusiastic wheelchair-enabled viewers, as well as nostalgic veterans of earlier activist eras and students hearing about the disability rights movement for the first time.

All of these will be released momentarily on streaming services, but the emotional lift of seeing well-crafted stories in company is one thing streamers don’t offer, and that we’ll miss until the viral season has passed.

Mayor movies.

One Sundance-to-True/False project that hasn’t been picked up by anyone yet, inexplicably, is Steve James’ four-part mini-series City So Real. (Over coffee, the ever-optimistic James said, “I’m lucky, this is the first time I’ve had this problem.”) It’s a superb ensemble work in which the city of Chicago is the central character. In the signature style of Kartemquin Films, the series has no narrator, using television news as the throughline to chronicle the process of the mayoral election. Corruption, patronage politics, and deeply ingrained racism inform the events at every step, most of them taken down at the neighbourhood level. But what an ending—the underdog reform candidate, an African-American lesbian, wins. The series has already shown us the challenges before her.

Amara Enyia joins the crowded field of mayoral candidates in Steve James’ Kartemquin Film, City So Real.

I loved every hour of the film. In fact, I’d like to go to a mini-festival just of mayor films; they can give you such a great perch to watch how local politics and culture inform each other. Think, for instance, of Chinese Mayor, Street Fight and the mini-series Brick City.

So it was natural that David Osit’s Mayor (an IDA Enterprise Documentary Fund grantee) was another fave for me. He chronicles a year in the life of Ramallah, the Palestinian town north of Jerusalem. Inside, mayor Musa Hadid copes with sewer breakdowns, power outages, unannounced invasions by Israeli military, and exasperated residents. His goal, in a town with no economic base but quite a few hipster coffee shops: To increase tourism. He’s focused on construction of a municipal fountain and a welcoming plaza outside city hall. Osit in Q&A said that, having been surprised by the charm of Ramallah, which he visited while studying refugee law, his goal was to make a film that could get beyond the usual media images of Palestine. “The film is about what leadership and authority look like in a place without leadership and being denied authority,” he said. “And I saw Musa’s evolution from being a beleaguered bureaucrat to being an activist.” Mayor Hadid was scheduled to attend, but COVID-19 cancelled his plans. Instead, he emailed his remarks, including an invitation to visit. You could get an “I [heart] Ramallah” button on exit.

U.S. Premieres.

Argentine director Eloisa Solaas’ The Faculties follows in the style of her documentary hero’s Frederick Wiseman in a film about a top-level Buenos Aires university. We arrive at the high-stress moment when students face their professors for an in-person exam. Whether it’s a well-briefed medical student combing through a model of wrist ligaments, awkward but determined law students in mock court, a student from a prison program asked about Marx’s theories of social change, or an utterly unprepared film student baffled by questions about the plot of Battleship Potemkin, it’s all high drama. Solaas manages with canny editing to hold audience attention, as students struggle to follow their dreams. She ends on a note of universal significance. Our imprisoned student is released, and we watch him attend his first class. It’s a lecture on the spread of neoliberal economics, a logic that denies the value of the free, accessible university education that everyone we have met gets. It’s a perfect ending to a film that’s about the power of education.

Ursula Liang’s Down a Dark Stairwell sensitively explores the conflicts that arise when a rookie Asian-American officer killed an innocent African-American man. Both ethnic communities organize to protect their own, with some organizers making tough choices. The film carries the Black Lives Matter discussion forward, bringing light to a heated topic. Eventually it’ll be on PBS’ Independent Lens, where with luck it will generate both reflection and conversation. It’s as topical and relevant as it gets.

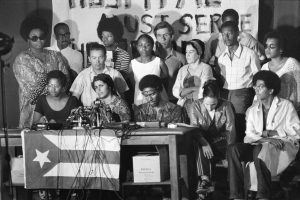

The Young Lords occupy Lincoln Hospital in the Bronx, in Dope Is Death.

Dope Is Death, Mia Donovan’s just-finished look back at a too-little-remembered movement for better health care, is alsorivetingly current. In the 1970s in the South Bronx, the Young Lords and the Black Panthers teamed up to offer methadone-free drug rehab programs. (If you want to understand what they hated about methadone treatments, Julia Reichert and Jim Klein’s 1975 exposé Methadone: Another Way of Dealing is a great watch.) The activists featured acupuncture at the core of the treatment, and surrounded the treatment with political education about the oppression of black and brown people. The practitioners, including clinic director Dr. Mutulu Shakur, trained with a left-wing Canadian doctor in Montreal.

This was the first connection to the story for Donovan, who is Canadian and lives in Montreal, where the doctor’s son Mario Wexu still lives. (In fact, he has become her acupuncturist.) She did not expect, she said in interview, to encounter the complex history the connection unraveled.

The clinic, a concession by a New York hospital to protests, was only kept open with more sit-ins and demonstrations. As the activists established international connections, especially with Maoist China, the CIA began to track them. COINTELPRO, the FBI project to surveil and disrupt dissidence, targeted them. In the political polarization of the era, leaders of the clinic also became involved in a bank robbery, which then sent them to prison. Mutulu Shakur (Tupac’s father) is still there; activists passed out cards connecting interested viewers to the mutulushakur.com website.

The film deftly deploys archival footage from many sources, interweaving it with forthright interviews not only with activists from the time but also from newer generations of patients who have themselves become activists and even acupuncture practitioners. “I wanted to make this film accessible to everyone,” she said in interview. “I think about my conservative aunts, and I want them to engage with the story.” To that end, she spends the first part of the film building viewers’ investment in the health issues and social crises of the South Bronx of the time, and she brings forward the often-ignored history of the Young Lords and the Black Panthers in community service. (There are echoes of this investment in Crip Camp; protesters occupying a building benefited from support from Black Panthers, who saw the disability movement as important to address oppression generally.)

“I hope that people can see, through this film, how health care is both political and politicized,” she said. It would be great to see this film soon widely in the U.S.

Reality questions.

It wouldn’t be True/False without some head-scratching questions about reality and the challenge of portraying it. That’s a perennial topic at the conference “Based on a True Story” (BOATS), held each year just before the festival at the University

In Bloody Nose, Empty Pockets, an actor who’s a barfly plays a barfly.

of Missouri’s legendary journalism program. This year the stars of the conference were Bill and Turner Ross, whose Bloody Nose, Empty Pockets showed at the festival, fresh from Sundance. The fest also threw them a retrospective, including Tchoupitoulas and 45365, and awarded them its True Vision award.

Bloody Nose is a stiff challenge to the category of documentary itself. The film takes place in a Las Vegas bar, the night before closing. The regulars gather for an increasingly inebriated celebration. The characters are vivid, their faces complex etchings of lives lived badly, their sentiments alternatively maudlin and boisterous. As the night progresses, the bartender’s young sons hang out in the alley, the next generation of barflies in waiting.

But the bar isn’t in Las Vegas; it’s in the Turner brothers’ home town of New Orleans. It’s not actually closing. The bar doesn’t usually look like that either; the brothers elaborately dressed the set, after renting the space. Those drunks aren’t regulars; they’re (mostly) non-actors the brothers hired for the day, offering a small stipend and an open bar tab. They’re following along on set-ups and narrative cues the brothers give them.

And nowhere in the film will you learn any of this.

So is this a documentary? It looks instead a lot like reality TV, but seedy.

When the brothers demonstrated their techniques at BOATS, they pointedly argued, as they’ve routinely done in the past, that they never asked for the label of documentarian. “Yes, we manufactured the experience,” said Turner cheerfully, “but it’s not a manufactured experience.” Rather, they said, what they had done was to establish the terms for authentic interactions and events. They had released the energy of reality.

At BOATS, in hallways and after screenings, some viewers expressed dismay at discovering that a film that they had assumed was a direct-cinema documentary, catching reality on the fly, was instead a crafted narrative. One said, “I don’t like that kind of betrayal of a viewer’s expectations.” Another asked whether this was exploitation of vulnerable people—impoverished alcoholics—in service of milking their authenticity for voyeurs. Still another had no problem with the film’s manipulations, but wanted transparency. Others pushed back, arguing that all documentary is a negotiation with reality, and that even fiction independent films that are low-low budget often have one-time non-SAG payments with actors.

But as is typical at film festivals and even film conferences that involve filmmakers, the criticism was rarely public. Indeed, when people voiced their concerns to me, they universally asked not to be quoted by name. For other filmmakers, criticizing one of their own would be reputational suicide. Professionals in the business work with everyone, and cannot afford to be seen picking a side. Even at BOATS, a conference led by academics at a journalism school, at discussions I attended the filmmakers were sources of information and appreciation, not challenged to justify their practices journalistically or ethically. Perhaps it’s impossible to hold such discussions with the maker in the room, or even nearby. The hallways, queues and bars of the True/False experience were a good if furtive start, though.

Making up the past.

Of all the True/False films that openly engaged with the true/false challenges in documentary, my personal favorite was The Metamorphosis of Birds, by Portuguese filmmaker Catarina Vasconcelos. The film is structured like a fable, told largely in tableaux and still lives, with a few artifacts as aides-mémoire. It recovers, partly in recreation and partly in re-imagination, the life of the filmmaker’s grandmother Beatriz, a sailor’s wife with six children. Her history had been lost, and recovering it, as we learn in the film, is part of the filmmaker’s own search for identity. The filmmaker narrates a richly metaphoric and evocative memoir of this work of re-imagining.

This is slow cinema, which can be torture–but not here. The clues are gracefully inserted, or take you by surprise (look for

In The Metamorphosis of Birds, magical-realist metaphors re-imagine the past.

Beatriz with the head of a bird). A magical-realist sentiment infuses the work. Sailors beam their love for family through Morse mode with signal lights into the uncaring sea. Objects—a fish, a child’s toy, an electrical outlet—become talismans for only partially-told stories. Tableaux hypnotize the viewer—I think of the moment when six adult children appear cloaked in sheets in the forest after their mother’s death, embodying one child’s comment, “We are ghosts.”

Vasconcelos definitely bends documentary in several ways. But she undeniably anchors herself in a lived reality, using metaphor, music, and composed image to evoke the work of imagination in reconstructing from fragments of the past. The film is reflexive, a document of her act of imagination. Toward the end of the film, she asks her father what he thinks of her retelling. Some of that didn’t happen, she recalls that he said. He is taken aback, among other things, by her changing of his first name for the film (his real name is the same as his dad’s, and she didn’t want to confuse viewers). That conversation is also an opportunity to reflect on her narrative and aesthetic choices, and not incidentally to let the viewer in on them. Transparency for her is part of the project.

Watching the watchers.

One of the most provocative of the films at True/False was The Viewing Booth, by Israeli filmmaker Ra’anan Alexandrowicz. The latest in Alexandrowicz’ long career of activist filmmaking about Israeli-Palestinian relationships, this film speaks not only to issues but to the function of documentary itself. It runs in the opposite direction of hybridity.

In The Viewing Booth, Israeli-American student Maia looks critically both at human rights videos and videos by the Israeli army.

The filmmaker’s work has included representing Palestinian viewpoints (The Inner Tour), and engaging with the Israeli judicial process in relation to Palestinians (The Law in These Parts). Alexandrowicz is no stranger to the staging of reality; The Inner Tour, which documents a trip Palestinians make to Israel, involved hiring a bus and driver and selecting the tour participants.

The Viewing Booth is a reach beyond either of his two earlier films. Alexandrowicz is in search of the most responsible way to use film to address the core question of his own life, of how to address the existential question of Israel’s future. After representing Palestinian viewpoints in his first film, he switched to focusing his lens on Israeli behavior. In this film, he asks how people experience human rights video.

“I’ve moved from filming the oppressed, to filming the oppressors, and now I am asking, How does the viewer see what the filmmaker is trying to do?” explained Alexandrowicz. “I am watching the watchers. This film is about the conflict between my motivations and reality.”

The film focuses attention on Maia, a Temple University undergrad who agrees to watch a variety of videos selected by the filmmaker, from the government and from B’Tselem, a human rights organization in support of Palestinian human rights. The film captures her reactions to the videos in real time as she challenges and analyzes them, also engaging with the filmmaker. Both viewing sessions raise troubling questions about how human-rights videos can be interpreted. Maia’s conversations with the filmmaker blossom into larger questions about whether and how documentary films make a difference, and to whom. (Alexandrowicz has expanded his thinking about viewers’ interactions with human rights imagery in a thoughtful multimedia essay.)

These are questions that can engage not only documentary filmmakers but activists, students and professors who care about the relationship between documentary film and reality. I hope the film has a long life, triggering discussion about how the role of documentary in addressing injustice and inequality.