The International Documentary Festival at Amsterdam (IDFA) is the annual über-showcase of documentary film from all over the world, and a pilgrimage site for doc lovers. Its temple is the Tuschinski Theater, a palace created in 1921 in a delirious mix of art deco and art nouveau and restored in the late 1990s. Abraham Tuschinski, the businessman who built it, was later murdered at Auschwitz, also making it a memorial to his legacy and a natural for hosting truth-telling events.

The International Documentary Festival at Amsterdam centers on the historic Tuschinski Theater.

That fits with a hallmark theme of IDFA, carried forward from the days of founder Ally Derks by new(ish) director Orwa Nyrabia: courageous truth-telling about human rights and public memory. This year among the foci were women’s voices and stories, and inclusion more generally.

Art and memory.

IDFA has a passionate audience. The Tuschinsky this year easily filled the main theater’s 1,200 seats for many showings, including on weekday mornings, and especially those for the films of festival guest of honor Patricio Guzmán.

“It was Chilean art that let the whole world know what happened in Chile,” Nyrabia said in opening a conversation with Guzmán and his life-partner Renate Sachse. Guzmán recalled the exuberant start of his long and increasingly melancholic career: the first year of socialist president Salvador Allende’s term, which ended in a brutal coup that shattered hopes and destroyed lives. Ever

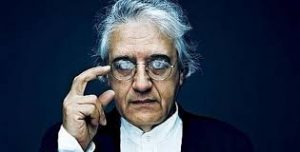

Patricio Guzmán was IDFA’s guest of honor.

since, Guzmán has been memorializing that trajectory and fiercely remembering what the later regime tried to bury. His latest film, Cordillera of Dreams, entirely merges his personal story with the story of Chile. In conversation with Nyrabia, Guzmán celebrated the current uprising in Chile of a people fed up with decades of neoliberal economics and politics, which has brought ever-increasing inequality. It brought the 1,200-person audience to their feet.

Although the IDFA Forum is all about the business of (quality) television, the 300+ films in the festival tend toward the less commercial. IDFA is also a bastion of cinéma verité, sometimes to the point where it seems the filmmakers have confused tedium with integrity.

The geographic range of the films on offer should astound, for the sheer logistics alone. And while character-driven narrative is the norm, you won’t be surprised to see works that creatively defy every expectation.

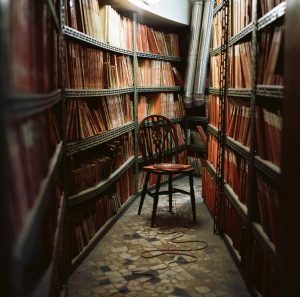

Sound as story.

At Belgrade Radio, an unwieldy library of recordings testifies to generations of cultural expression.

The film that took the top of my head off was Speak so I Can See You, by Serbian filmmaker Marija Stojnić. It’s on another planet from character-driven narrative, in a good way. During unexpected downtime in her homeland, she stumbled upon one of Serbia’s more remarkable cultural resources, Belgrade Radio. This last-of-its-kind station eclectically samples the history of Western culture, to offer everything from hours-long discussions of philosophy texts to harpsichord performance to opera and radio plays. Stojnić makes sound the central actor of a film that unobtrusively follows the radio staff in their daily rounds in their moldy, Tito-era offices, working with aged computers and equipment. As renovations begin, she interweaves rich material from the station’s archives, providing snippets of Yugoslav and Serbian history on the way.

Close watching reveals provocative alignment of image and sound, further driving viewers to attend to the soundtrack, and to think about what gets lost with renovation. While the meaning of the layered film will be more resonant with Serbians, it deserves screenings beyond the documentary community. Art museums should embrace it. Radio aficionados will fall in love with it, and historians will treasure it.

Hidden histories.

I was surprised and grateful to learn about cinemas I hadn’t ever once thought about. Afghan-Canadian Ariel Nasr’s The Forbidden Reel (a National Film Board of Canada [NFB] project) retraces the history of Afghan cinema, deeply intertwined with politics. There’s the early state cinema, then a rollicking period of immensely popular genre cinema catering to modernist city-dwellers. As they watch romances and action films, in the hills mujahideen use video to chronicle their rebellion. It all comes to a head when the Taliban take over Kabul, and film archivists get a tip to squirrel away their most precious work before it’s destroyed. It’s these hidden treasures that Nasr mines to tell a sometimes jaw-dropping story. Now, NFB is also helping restore the Afghan film archive.

The poignant Talking about Trees (Suhaib Gasmelbari) also revealed a cinematic past in Sudan, where once outdoor cinemas were popular. A group of elders gather in hopes of being able to host just one showing of a popular film (they pick Django Unchained), but they are up against not only endemic poverty and a zero budget, but the deep hostility of the Islamist government to both public gatherings and cinema. It’s particularly intriguing to see how important cinema was to the very sense of identity of these four old men.

Strong women.

In Sunless Shadows, Iranian women who killed their husbands or fathers tell their stories.

Several films celebrated, in different ways, heretofore unsung strong women. Carol Benjamin’s I Owe You a Letter about Brazil delves into family history. Her father was jailed and then exiled from Brazil to Sweden, during the same grim period of dictatorship that Chile and Argentina experienced. The film focuses on her grandmother, who, unbeknownst to her son in solitary confinement, was waging a dangerous, unrelenting, and ultimately successful public campaign for him and other political prisoners to be freed to exile. Most interesting, though, is the story of her post-dictatorship life, in which she continued to be an outspoken but often unappreciated activist, who struggled with depression, loss and lack of public identity. The film simultaneously—and with help from the endlessly rich Swedish television archives—recovers history and poses a challenge to explore the hidden costs of women’s work. The film got a special jury mention for First Appearance.

In Sunless Shadows, noted Iranian filmmaker Mehrdad Oskouei takes us inside a prison for Iranian women and girls who have murdered family members. Their rapport with the filmmaker is manifest; they joke with him (although we never see him), talk over each other, laugh, cry. It’s like a sleepover in prison. Their stories all take place in the long shadow of domestic abuse, whether from husbands, fathers or other family members. A young girl driven to murder by the routine sight of her mother’s suffering; a young wife who escaped an abusive home to an even more abusive husband; a mother who hoped only to free her children. Perhaps most remarkable is a young woman who, previously incarcerated, regularly returns to the prison, where she finds more of a family and a life than she can, as a convicted murder and single woman, on the outside. The film won Best Directing award.

Let’s Talk is in another flavor altogether. Filmmaker Marianne Khoury is the niece of legendary Egyptian filmmaker Youssef Chahine, and his longtime producer. Against his every admonition, she decided to make documentary films about otherwise-invisible women. Let’s talk, her latest work, is her own personal memoir and exploration of female relationships in a family well ensconced in the Egyptian cultural elite (they speak French at home). Deliberately disjointed and troubling, the film explores the identity challenges of her mother, her daughter and herself. The greatest challenge may not be the formal ones (many video formats, jerky edits), or even the historical ones (the linking of Shahine’s most famous autobiographical films with the family’s history), but the fact that Khoury’s daughter appears petulant, hostile and utterly self-absorbed.

A Mexico City bar dressing-room attendant has a rich past, which echoes with the stories of the dancers who change there.

Other examples of strong women featured in film include Angels on Diamond Street (Petr Lom), about the church that offers daily dinners for the homeless and became a sanctuary for a Central American undocumented family. Both the miserable, trapped mother of the family, and the tough but loving cook are stars. In Wintopia, Mira Burt-Wintonick’s portrait of her father, the IDFA-beloved icon Peter Wintonick, her mother ends up being more of a hero than you might have suspected. Maasja Ooms’ Punks, which and, in what can feel like real time, soberly tells a heartbreaking story of a rehab center cum farm that works with troubled young men, is anchored by the extraordinary woman who runs the farm. (It won Best Editing.) Laura Herrero Garvin’s La Mami engagingly features a bathroom attendant with a long history as a bargirl, who counsels the current crop of hardluck dancers trying to get along. I was sorry to have to miss In a Whisper (Heidi Hassan and Patricia Pérez Fernández), which won Best Feature-Length Doc, about two childhood friends whose Cuban childhood unites them across time and distance.

Crusading journalists.

Crusading journalist Carmen Aristegui stands up for journalism’s role in democracy.

But if you want a strong woman, then Carmen Aristegui is a standout. She is the center and hero of Juliana Fanjul’s Radio Silence, which chronicles the fearless journalist’s firing from a major TV station, the creation of her online video site, and her launching of an independent radio station. Not only is launching new journalism in a country where most journalism is directly supported by the state enormously taxing. She is also surveilled, and faces daily threats to her life. This portrait is crisply told in a style that doesn’t glorify her, and also doesn’t downplay the risks. Aristegui is not only an extraordinary journalist, but also an example of the crisis of journalism in Mexico. Investigative documentarians and journalists should pay attention.

And the problem isn’t just in Mexico, as we see in Canadian Yung Chang’s This Is Not a Movie (an NFB production). Robert Fisk has been reporting on the Middle East for decades, for several major British newspapers. He’s the rare journalist who’s also permitted to express an editorial opinion, and is legendary on this beat. Chang mines archives to put Fisk in battle after war after crisis. Fisk responds bluntly, thoughtfully and productively on various myths of journalism. He points out if you actually do know anything about the region, and overcome the journalist-from-Mars syndrome, that you are inevitably accused of bias. He’s sure that the continuing tragedy of the region goes right back to colonialism, the crude breakup into mismatched states, and continuing neocolonialism, and he knows enough about both present and past to back up his case. Unpretentious, courageous, and in constant danger, he is a foreign correspondent who is acutely aware of the limits of journalistic knowledge, the hubris of the foreigner, and of the importance of historical context. This is another film that should be taught in journalism programs everywhere.

Exposes.

Many other films excellently and differently revealed hidden stories that deserve wider attention. Lucy Parker’s Solidarity rousingly chronicles a decade-long struggle by working groups to expose surveillance by anti-labor consultants working with industry to suppress workers’ rights in Britain. There are jaw-dropping stories here. Parker won the top award for First Appearance. Aswang (Alyx Aum Arumpac) takes us inside Duterte’s drug war in the Philipppines, where families are torn apart and there is no judicial recourse. It won the FIPRESCI award in First Appearance. Fredrik Gertten’s Push earnestly and clearly

Beijing’s air pollution reaches crisis in Smog Town.

shows how housing shortages for working people are related to late-capitalist million/billionaires’ purchases of real estate for speculation, money laundering and asset-parking. Marlene Edoyan’s The Sea Between Us reveals the huge continuing tension between Christians and Muslims in today’s Lebanon, through two women’s daily lives. In The Forum, Marcus Vetter (The Cleaners) gets unprecedented access to Davos. At some length and with a lot of talk (I’m imagining the film gets a haircut before its commercial release), it persuaded me that putting the rich and famous together reinforces the parlous status quo, despite the manifestly good intentions of Davos’ idealistic founder.

Meng Han’s Smog Town excellently shows off a trend toward creative, independent documentary from China aimed at global audiences. It follows an environmental official in suburban Beijing, responsible for lowering air pollution but unable to get help from the economic development folks stoking the factories, construction firms or city government generally. The access is exceptional, and the central characters are complex. The fix the head official is in may be specific to China, but it’s emblematic of the way governments across the world are failing to face tough choices.

Recombinant cinema and fair use.

One of IDFA’s more unusual strands this year was “Re-releasing history,” a retrospective showcase of films composed mainly of archival material. Along with film legends such as the 1982 The Atomic Café and the 2013 The Stuart Hall Project, David Shields’ Marshawn Lynch: A History showed. It won a special jury mention for creative use of archive.

Filmmaker David Shields couldn’t have made Marshawn Lynch: A History without fair use.

Former NFL runningback Marshawn Lynch has become as famous for his stoic silence in front of the press as for his extraordinary capacity to outrun his opponents on the field. Using footage from Black Panther-made film, NFL games, lynching photos, excerpts from Richard Pryor routines, and much, much more, Shields assembles a rapid-fire continuous montage intended to audio-visually mimic Lynch’s running style. In the process, he contextualizes Lynch’s silence in a history of African-American resistance.

Almost all the material in Marshawn Lynch was fairly used. As an author accustomed to collage—his book Reality Hunger became a best seller—Shields was already familiar with fair use, the right to reuse copyrighted material without licensing, under some circumstances. He consistently applied a transformative logic (are you re-using the material for a different purpose you can articulate? Is the amount appropriate to that purpose?). In spite of the fact the film draws from major corporate entertainment products and sports franchises, it has not been challenged. Indeed, the film is widely available, on Google Play, iTunes, Amazon, and more.