This article was originally posted on Documentary.org.

The final chord of “the Blackfish effect” has finally resounded, with a stunning and unprecedented corporate policy announcement from SeaWorld.

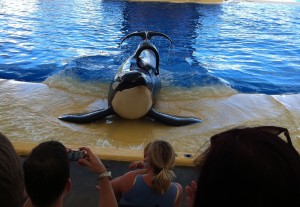

Courtesy of Dogwoof

In January 2013, the documentary Blackfish premiered at the Sundance Film Festival, telling the story “about Tilikum, a performing killer whale that killed several people while in captivity,” according to the official film synopsis. Three years later—a period marked by sustained activism, multi-platform distribution and unrelenting media coverage— SeaWorld officially announced on March 17, 2016, that it will officially end its orca breeding program and end orca shows at all of its theme parks.

The decision didn’t happen overnight, and neither did the social impact. The pathway to change was paved over three years of ongoing pressure, sparked by an emotional story told in an intimate, authentic way unique to documentary storytelling. The signs of social impact appeared quickly. In December 2014, about a year and a half after the film’s July 2013 theatrical premiere, the stock price of SeaWorld had already declined by 60 percent. A California state lawmaker proposed legislation in April 2014 that would have banned California aquatic parks from featuring orcas in performances. Although the proposed law was unsuccessful, it garnered national media coverage and elevated the issue.

How and why did Blackfish inspire this kind of impact over a three-year period of time? From a vantage point at the intersection of documentary storytelling, grassroots activism, multi-platform distribution and media strategy, the explanation can be broken down into six key elements:

1) Amplified Community and Sustained Grassroots Activism

The issue of animal rights is supported by an existing and vocal community of advocates, and the opportunity was ripe for cultivating new activism by the time Blackfish came along. The Oceanic Preservation Society, the organization elevated by the 2009 Academy Award-winning documentary The Cove, publicly and immediately supported Blackfishthrough its own communication channels, including posting and distributing an online open letter to support the film, and joining with the filmmakers in a public statement. The major contribution of the grassroots infrastructure to the Blackfish movement came from PETA (People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals); in fact, the intersection between the film and the organization’s activism amplified the ongoing impact dramatically. In an expansion of its own efforts targeting SeaWorld as far back as 1998, PETA launched an aggressive renewed campaign that combined physical protest and digital social action. After the film’s major premiere on CNN, donations to PETA—formerly on the decline—spiked, enabling the group to finance continued grassroots and media stunts well after the film’s premiere. (In 2015, as reported by the Los Angeles Times, PETA reported a budget of $4.5 million after a deficit of more than $250,000 just two years earlier, as well as $43 million in contributions in 2015, a 30 percent increase.)

With the new public spotlight well beyond the animal welfare community, PETA continued to leverage the momentum of the film at every possible moment in the distribution and media cycle. Among its public actions during the past three “BlackfishEffect” years, PETA organized anti-SeaWorld actions at the 2014 Rose Bowl Parade—covered by major media outlets, including CNN, Blackfish‘s broadcaster, Huffington Postand others—and financed an ad campaign about orca breeding (an angle covered in the film). PETA’s website, SeaWorldofHurt.com, continued the pressure and momentum, and the public followed—from about “30 visitors per day before the Blackfish broadcast premiere to more than 1 million in 2015.

In short, the film wasn’t released into a cultural or grassroots vacuum. It fell into a prime spot with a social-change infrastructure ready to leverage a strategic distribution strategy and well-produced story. In its seminal 2008 report, “Assessing Creative Media’s Social Impact,” The Fledgling Fund notably wrote about this crucial element—deeply understanding the social issue and a movement in order to understand where and how a story might be positioned to fuel change. The intersection between SeaWorld, Blackfishand PETA is a textbook example.

Adding to the well-orchestrated and vocal NGO activism, celebrities’ tweets and support for the film engaged their own fans and followers, which raised and deepened the level of public awareness about the story. Combining the multiplying factor of celebrity endorsements and public attention—greatly enabled by a smart distribution strategy—allowed the story to reach outside the animal welfare community. It stretched well beyond the choir. The outcry became louder and louder, impossible to ignore or dismiss as insular, niche activism.

Courtesy of Dogwoof

2) Strategic Distribution

Following the Sundance Film Festival premiere, the filmmakers licensed the US rights forBlackfish to Magnolia Pictures and CNN Films, not only for a theatrical run, but for TV distribution, a move that has become increasingly strategic for documentary filmmakers in the contemporary marketplace. In at least one study about contemporary documentary viewers, watching at home on TV is the top way to access documentaries, and streaming is increasingly crucial (although avid documentary enthusiasts are also willing to find documentaries in theaters). For Blackfish, in terms of a broad-appeal TV outlet with aneven-handed ideological audience composition, a premiere on CNN was not only a mass-viewer distribution strategy, but one that fired up a synergistic publicity and news media machine. Not only did the network use its news platform to air stories about orcas in captivity, the network published an interview with a SeaWorld spokesperson the week of the premiere, assuredly contributing to viewer and media anticipation. CNN was rewarded for its publicity strategy with a ratings sweep on the October 23, 2013, premiere date; according to The New York Times, “The channel swept the ratings among every group under 55 years old. That meant not only the group that is most often sold to news advertisers, viewers ages 25 to 54, but also the younger age groups used for sales in entertainment programming.” The network continued to keep the story on the agenda by illustrating multiple sides of the issue, including at least one opinion piece criticizing the film’s lack of focus on marine conservation in aquatic parks. Following the CNN broadcast, in a near-perfect multifaceted distribution strategy primed for visibility,Blackfish was released on Netflix in December 2013, which enabled the film to leverage the considerable publicity and buzz already generated by the steady media coverage throughout every distribution phase.

3) Media Coverage

The film’s profile increased as SeaWorld and the filmmakers engaged in a prolonged public relations battle, in addition to the media coverage already garnered by activist stunts from PETA. In the days leading up to the film’s theatrical distribution in July 2013,SeaWorld’s PR firm released a statement that spotlighted claims of misrepresentations in the film. Film critics and other media outlets picked up the SeaWorld statement and the filmmakers’ response, which amplified the coverage and raised public awareness of the film. In a New York Times article prompted by the exchange, writer Michael Cieply mused, “The exchange is now promising to test just how far a business can, or should, go in trying to disrupt the powerful negative imagery that comes with the rollout of documentary exposés.” Well after the theatrical premiere, the campaigns continued, with the filmmakers responding publicly on the movie’s website in January 2014. The PR war magnified the media coverage and the public’s interest in the story— and crucially, not only during the theatrical distribution period in July 2013, but also during its TV premiere in October and streaming release at the end of the year. (Read SeaWorld’s statement, “Blackfish: The Truth about the Movie,” here.)

4) Social Action Embedded in the Story

Social action campaigns around documentary films can vary from the filmmaking teams’ intentional strategies to organic responses from viewers to a story. In an ideal strategic scenario, the organic viewer response to the story is matched by an intentional campaign, if it exists. But in either case, the call-to-action efforts tend to succeed when the action is clear—and when it is conveyed by the film’s story itself (not only the marketing materials around it). In stories with institutional or complex solutions, articulating a call to action can be challenging, but offering concrete individual actions works. In the case of Blackfish, although the social action directives were not directly articulated or advanced by the filmmakers, the identification of Tilikum’s captive home was clearly embedded in the story itself. The audience understood SeaWorld’s role, and the film’s advocacy story about orcas in captivity issued a clarion call. (It’s important to note that in an early interview, director Gabriela Cowperthwaite did not advocate shutting down SeaWorld but instead discussed other ways to help captive orcas. Of the final SeaWorld announcement, though, Cowperthwaite said, “The fact that SeaWorld is doing away with orca breeding marks truly meaningful change.”)

Courtesy of Dogwoof

5) Emotion

The story evoked empathy, an emotional response that is an evidence-based powerful driver of attitude shift and intended action in response to storytelling. Blackfish focused on a specific named orca living in captivity, Tilikum, as the key character, a deliberate narrative choice made by the filmmaker. She did not lead with or rely on statistics, and it turns out, this really matters in a story’s ability to spark emotion and action. Although research in the area of narrative persuasion focuses primarily on human victims of suffering, according to psychologist Paul Slovic, “When it comes to eliciting compassion, the identified individual victim, with a face and a name, has no peer…But the face need not even be human to motivate powerful intervention.” This core notion of empathy and an individual story can help to explain why the story evoked such resonance from a narrative perspective. Tactics alone won’t do the trick.

6) Measurable

Capturing the measurable social impact of a documentary is highly individualized, with varying research methods and approaches that work. The best method depends on either the goal of the project or simply a hypothesis and a deep understanding about what kind of impact the film may have on the issue, based on an understanding of where the issue resides in media or public discourse—from changing personal behavior to instituting policy change and beyond. In the case of Blackfish, the intersection of both organic and organized social action, constant media coverage, and accessible financial data from a publicly traded company provided some metrics of correlational impact. The readily available metrics emerged steadily, from mid-2014 media reports about SeaWorld’s financial trouble to a Washington Post analysis from December 2014, which detailed a steady stock-price decline throughout the film’s life cycle from theatrical to streaming distribution in 2013. The ongoing metrics of doom offered encouragement for the grassroots efforts. Each publicly available signal of decline, from attendance to stock price, offered a new opportunity for the ongoing SeaWorld-Blackfish media story to renew itself and keep the issue in the public and journalistic spotlight.

Can the film claim a final causal connection to the reported financial misfortune and sustained public outcry and the final SeaWorld announcement? In the same way that much social change can’t be unequivocally attributed to a particular and exacting turn of events, not precisely. But causal connection is an artificially high bar. It’s hard to deny the role of the “Blackfish effect” in the steady negative impact that culminated in a dramatic corporate policy change.

Considering documentary film and TV’s increased role as advocacy-infused, emotional investigative storytelling, as well as the increased ability for audiences to watch documentaries on places like Netflix, CNN Films, HBO, PBS and other outlets, individuals and organizations working at the intersection of social justice and media are right to learn from this example.

Caty Borum Chattoo is a documentary film producer, media strategist and researcher, professor and co-director of the Center for Media & Social Impact at American University’s School of Communication in Washington, DC. She was a juror for the international 2014 BRITDOC Documentary Impact Awards, which honored Blackfish as a film that demonstrated positive social impact.