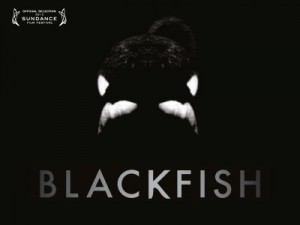

In January 2013, the documentary “Blackfish” premiered at the Sundance Film Festival, telling the story “about Tilikum, a performing killer whale that killed several people while in captivity,” according to the official film synopsis. Nearly two years later, the film’s impact continues to ripple out.

January 2013, the documentary “Blackfish” premiered at the Sundance Film Festival, telling the story “about Tilikum, a performing killer whale that killed several people while in captivity,” according to the official film synopsis. Nearly two years later, the film’s impact continues to ripple out.

According to a December 2014 Washington Post story, the stock price of Tilikum’s home park, SeaWorld, has declined by 60 percent since the film’s July 2013 theatrical premiere. A California state lawmaker proposed legislation in April 2014 that would ban California aquatic parks from featuring orcas in performances, although the proposed law is now on hold pending further study. And, in June 2014, inspired by “Blackfish,” the U.S. House of Representatives expressed official interest in studying the impact of captivity on orcas and other marine animals.

Whether or not these indicators lead to institutional change remains to be seen. Regardless, it’s worth asking why and how “Blackfish” inspired this kind of impact. From a vantage point at the intersection of documentary storytelling, media strategy and research, here’s a look at six key elements:

(1) Amplified Community.

The issue of animal rights is supported by an existing and vocal community of advocates. The Oceanic Preservation Society, the organization behind the 2009 Academy-Award-winning documentary “The Cove,” publicly supported “Blackfish” through its own communication channels, including posting and distributing an online open letter to support the film, and joining with the filmmakers in a public statement. In an expansion of its own efforts, PETA (People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals) launched an aggressivecampaign that combined physical protest and digital social action. Celebrities’ tweets and support for the film engaged their own fans and followers, which raised and deepened the level of public awareness about the story.

Beyond the vocal work of a core group of supporters, combining the multiplying factor of celebrity endorsements and public attention – greatly enabled by a smart distribution strategy (see below) – allowed the story to reach outside the animal-welfare community to new audiences and supporters.

(2) Strategic Distribution.

Following the Sundance Film Festival premiere, the filmmakers licensed the U.S. rights for “Blackfish” to Magnolia Pictures and CNN Films, not only for a theatrical run, but for TV distribution, a move that has become increasingly strategic for documentary filmmakers in the contemporary marketplace. In at least one study about contemporary documentary viewers, watching at home on TV is the top way to access documentaries, and streaming is increasingly crucial (although avid documentary enthusiasts are willing to find documentaries in theaters, as well). For “Blackfish,” in terms of a broad-appeal TV outlet with an even-handed ideological audience composition, a premiere on CNN was not only a mass-viewer distribution strategy, but one that fired up a synergistic publicity and news media machine. Not only did the network use its news platform to air stories about orcas in captivity, the network published an interview with a SeaWorld spokesperson the week of the premiere, assuredly contributing to viewer and media anticipation.

CNN was rewarded for its publicity strategy with a ratings sweep on the October 23, 2013, premiere date; according to The New York Times, “The channel swept the ratings among every group under 55 years old. That meant not only the group that is most often sold to news advertisers, viewers ages 25 to 54, but also the younger age groups used for sales in entertainment programming.” The network continued to keep the story on the agenda by illustrating multiple sides of the issue, including at least one opinion piece criticizing the film’s lack of focus on marine conservation in aquatic parks. Following the CNN broadcast, in a near-perfect multifaceted distribution strategy primed for visibility, “Blackfish” was released on Netflix in December 2013, which enabled the film to leverage the considerable publicity and buzz already generated by the steady media coverage throughout every distribution phase.

(3) Media Coverage.

The public relations battle between SeaWorld and the filmmakers helped raise the documentary’s profile. In the days leading up to the film’s theatrical distribution in July 2013, SeaWorld’s PR firm released a statement that spotlighted claims of misrepresentations in the film. Film critics and other media outlets picked up the SeaWorld statement and the filmmakers’ response, which amplified the coverage and raised public awareness of the film. In a New York Times article prompted by the exchange, writer Michael Cieply mused, “The exchange is now promising to test just how far a business can, or should, go in trying to disrupt the powerful negative imagery that comes with the rollout of documentary exposés.” Well after the theatrical premiere, the campaigns continued, with the filmmakersresponding publicly on the movie’s website in January 2014.

The PR war almost certainly magnified the media coverage and the public’s interest in the story – and crucially, not only during the theatrical distribution period in July 2013, but also during its TV premiere in October and streaming release at the end of the year. (Read SeaWorld’s statement, “Blackfish: The Truth About the Movie,” here.)

(4) Social Action Embedded in the Story.

Social action campaigns around documentary films can vary from the filmmaking teams’ intentional strategies to organic responses from viewers to a story; in an ideal scenario, the organic viewer response to the story is matched by an intentional campaign, if it exists. But in either case, the call-to-action efforts tend to succeed when the action is clear, and when it is conveyed or implied by the story itself (not only the marketing materials around it). In stories with institutional or complex solutions, articulating a call to action poses a challenge, but one in which offering concrete individual actions can be a partial answer.

In the case of “Blackfish,” although the social action directives were not directly articulated or advanced by the filmmakers, the identification of Tilikum’s captive home was clearly embedded in the story itself. The film’s advocacy story about orcas in captivity issued a clarion call. (It’s worth mentioning that in an early interview, director Gabriela Cowperthwaite did not advocate shutting down SeaWorld but instead discussed other ways to help captive orcas.)

(5) Emotion.

The story evoked empathy, an emotional response that may be a powerful driver of action in response to storytelling. “Blackfish” focused on a specific named orca living in captivity, Tilikum, as the key character, a deliberate narrative choice made by the filmmaker, rather than leading with or heavily relying on statistics. Although research in the area of narrative persuasion and entertainment-education deals with human victims of suffering, according to psychologist Paul Slovic, “When it comes to eliciting compassion, the identified individual victim, with a face and a name, has no peer…But the face need not even be human to motivate powerful intervention.” This is merely a hypothesis, of course, about why the story evoked such resonance from a narrative perspective, beyond the strategic elements like an active community, celebrity endorsements, ongoing media coverage and the rest. But it may be a hypothesis worth exploring.

(6) Measurable.

Capturing the measurable social impact of a documentary is highly individualized, withvarying research methods and approaches that work, depending upon either the goal of the project or simply a hypothesis about what kind of impact the film may have – from changing personal behavior to instituting policy change and beyond. In the case of “Blackfish,” the intersection of both organic and organized social action, constant media coverage, and accessible financial data from a publicly-traded company provided some metrics of correlational impact. The readily-available metrics emerged steadily, from mid-2014 media reports about SeaWorld’s financial trouble to the most recent Washington Post analysis from December 2014, which detailed a steady stock-price decline throughout the film’s life cycle from theatrical to streaming distribution in 2013.

Can the film claim a causal connection to the reported financial misfortune, per se? No, but this is the case with almost all social science and market research conducted outside an experimental lab scenario. Public opinion research or an examination of the changing media public discourse around the issue of marine animals in captivity would be important contributions to understanding the story of “Blackfish.” Measurable impact also includes policy or corporate change, and in this case, it’s worth continuing to pay attention to the evolution in both areas.

Over at the Center for Media & Social Impact, we spend a great deal of time chronicling the blueprints of documentaries, stories and campaigns that lead to observable social impact. Impact starts and ends with a story well-told, but amplification and social impact require community engagement and media attention in a “design for impact” model. And, in an ideal world, appropriate research methods are identified early – and incorporated throughout the process – to help tell the story about impact and provide ideas for future stories to come.

“Blackfish” was one of the recipients of the 2014 BRITDOC Impact Award

Blackfish from BRITDOC Foundation on Vimeo.