AN URGENT NEED TO SUPPORT DOC FILMMAKERS AND PUBLIC TELEVISION

American independent documentary filmmakers are among our nation’s precious creative assets, both journalistically and aesthetically. These are the people who find the untold stories and tell them in distinctive, authentic voices with editorial independence. They are the artists who embody and chronicle America’s diversity. Their stories document our present and past, and become part of our national memory and our educational systems.

The pandemic put that precious resource at risk. Filmmakers like other artists have been disproportionately affected by the economic challenges of Covid-19. In April 2020, nearly three- quarters of film professionals were fully unemployed because of the pandemic. Filmmakers who identify as BIPOC, LGBT+ or as living with disabilities are unemployed at particularly high rates.22 In October 2020, Californians for the Arts reported that a third of cultural sector employees were unemployed.23 By contrast, national unemployment rates overall fell from about 15% in April to less than 7% in December 2020.24

These short-term losses have turned into career and field-threatening crises. In April 2021, a national survey of documentary filmmakers showed how deep the pandemic crisis is in the field. Two-thirds of all filmmakers reported significant losses from the pandemic, and nearly half of those reported those losses as profound.25 The crisis for filmmakers imperils the pipeline of production, particularly for those most vulnerable—emerging, BIPOC, and other marginalized groups, the very groups that public broadcasting has, through ITVS and minority initiatives, historically supported.

The pandemic has delivered a body blow to independent filmmaking ecology. This puts the pipeline at risk, particularly for marginalized voices.

Documentary production has grown dramatically in the last three decades as production fueled by Discovery, National Geographic, Amazon, Netflix, Hulu and niche content providers shows us. Yet too little of this content serves the needs of a democratic public. Commercial imperatives of course set priorities. As filmmaker Amy Ziering noted in The Hollywood Reporter, “As the streamers consolidate, the options become more limited…Now they’re chasing algorithms much more, and it’s more clickbait than integrity. It’s less investigative journalism getting funded.”26 And sometimes, filmmakers tell us (as does the New York Times), big streamers avoid films on important issues—such as the murder of journalist Jamal Khashoggi, and the death of Kim Jong-un’s brother—that might complicate their global businesses.27

U.S. public broadcasting has long been a trusted outlet for independent filmmakers. In fact, documentary filmmaking and public broadcasting have grown up together, and mutually built strength and creative approaches to tell meaningful American stories. It was independent filmmakers who pioneered such innovations as cinéma vérité, the historical mini-series, the personal essay documentary, and the hybrid documentary—all on public television. It was independent filmmakers who brought home to all Americans, with Blackside Productions’ Eyes on the Prize, the truth that Civil Rights history was core to American history—on public television. It was independent filmmakers who brought to public television the commitment to community engagement on important social issues, using independently-made documentaries as a platform to launch transformative discussions both nationally and in local communities.

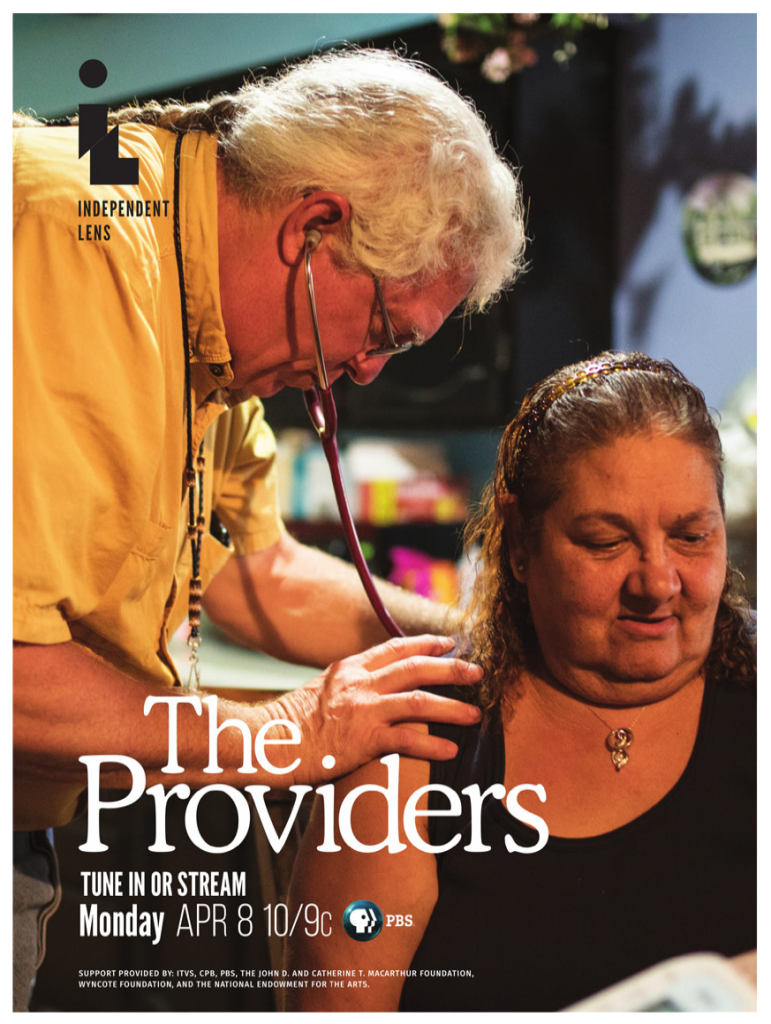

The challenge of accessing health care rings true throughout America as evidenced by the 2.6 million people who tuned in to watch the PBS broadcast of THE PROVIDERS. The ITVS co-production catalyzed civic dialogue at 98 local community screening events throughout the country.

The filmmakers we interviewed sometimes used the term “PBS Baby” to describe the way they came up within the system. They love what public television delivers in terms of reach, branding and local engagement at the station level. “I get to make the film I want to make, and I get help with [civic] engagement, which no commercial outlet will do,” said one filmmaker who co-produced a documentary with ITVS.

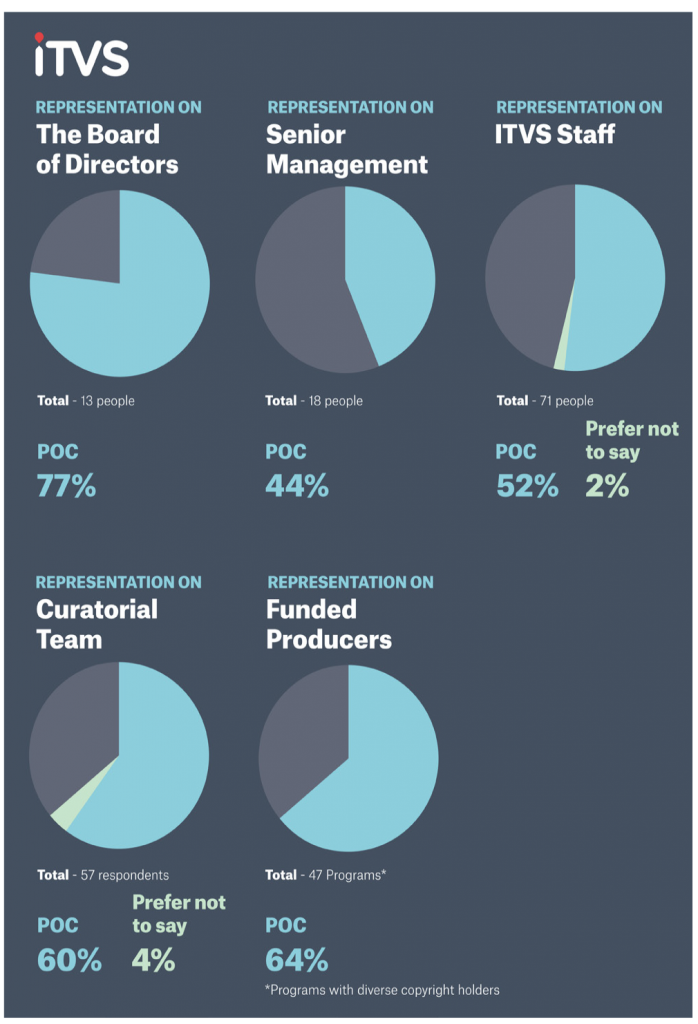

But too often they experienced public television as an obstacle course, rather than a service that is designed to support the production and distribution of their work. We listened to filmmaker after filmmaker describe the need for public broadcasting to have a more consistent, supportive approach to ensure that inclusive documentary storytelling reaches Americans where they live. “What does public media look like, when BIPOC people are 40% of the population?” one BIPOC filmmaker asked. “We need to be in that conversation.” Filmmakers living with disabilities told us that their community—the largest minority group in the country—is routinely ignored, and needs to be seen and heard in all its creativity and diversity. “We’re over being your afterthought,” one said. Shortly after interviews closed, this issue became more public. In spring 2021, BIPOC filmmakers from a newly formed organization, Beyond Inclusion, challenged PBS to provide full data on PBS’ history with BIPOC production, calling for “meaningful dialogue and action, and to engage BIPOC filmmakers as we chart a course forward.”28 Although we do not yet have PBS data, ITVS data, analyzed independently by scholars, shows that public TV programming by independent producers, through Independent Lens and POV, is remarkably more racially diverse than other programs on public TV. Indeed, some commercial series are more racially diverse than some leading public TV series.29

A 2021 Peabody Award winner, the five-part film series ASIAN AMERICANS led by producer Renee Tajima-Peña came to life through the collaborative efforts of WETA, PBS, and the Center for Asian American Media in association with ITVS. It examines the impact of Asian Americans in shaping America’s history and identity.

The gap in support extends to public television’s production budgets, which are no longer competitive. “Public television is stuck at a budget level from 15 to 20 years ago. It’s a much more competitive landscape today,” one filmmaker told us. “It’s not working to spend 10 years to make a movie while you’re putting funding together,” another BIPOC filmmaker said. Filmmakers were frustrated with lack of support between films, as well, and with the need to piece together budgets from different parts of public television and private funders.

Documentary filmmakers who intend their work primarily as a catalyst for civic engagement told us that their strongest motivation is contributing to meaningful social change. Few documentary films on social issues make a profit.30 Inconsistent support from public television meant that social-issue filmmakers often had to find commercial projects with cable or streamers, take up gig work using their technical skills, or find other ways to survive.

“PBS was the only place that would let me use my Black voice and creative ability to tell the stories I wanted to tell. I wish PBS did a better job of letting the world know that.”

Independent documentary filmmaker