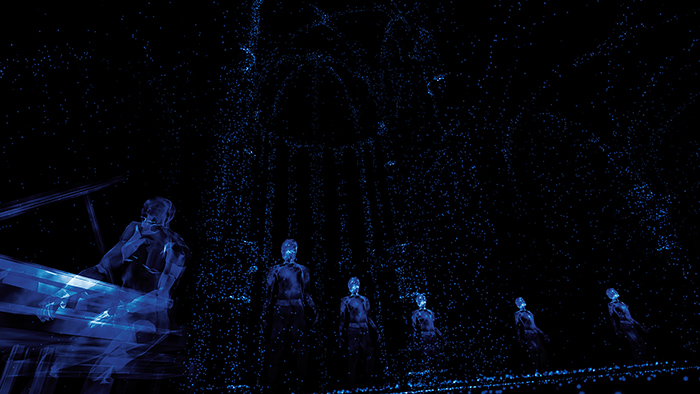

From Condition One’s ‘In the Presence of Animals’ (Dirs.: Danfung Dennis, Casey Brown, Phil McNally). Photo: Casey Brown. Courtesy of Sundance Film Festival

This article was originally published in the Spring 2016 edition of Documentary magazine, a publication of the International Documentary Association. Read it here.

Following a brief test run in the 1990s, virtual reality has rapidly taken hold over the past few years as a potent tool for exploring the possibilities of storytelling—first among the gaming community, then among such early adaptors as Nonny de la Pena, who started in journalism. The Sundance Film Festival, Tribeca Film Festival and SXSW have all incorporated VR programming into their respective new media mixes, and the medium hit the mainstream in Fall 2015 when The New York Times distributed Google Cardboard viewers to 1.5 million subscribers to experience what The Old Gray Lady has to offer through the double lens.

But what goes into producing and editing these VR projects? How far removed is the process from the skill set required for making “flatties”? Documentary tracked down some of leading purveyors of this new form to share their experiences and the specific challenges of working in this immersive medium.

Danfung Dennis, founder and CEO of Condition One.

For Danfung Dennis, former war photographer and an Academy Award-nominated filmmaker for his documentary Hell and Back Again, virtual reality is a natural transition. “I’m following in the tradition of bearing witness to suffering,” says Dennis. “It’s been a continuation from photojournalism to documentary film and now into virtual reality.”

His VR production company, Condition One, is currently circulating a number of pieces. For each of these, the goal is to create “presence”—the feeling of being at the scene. But how to achieve and describe that presence? That’s something documentary filmmakers working in VR are still experimenting with.

“We’re no longer trying to work within a frame,” says Dennis. “So the techniques and the storytelling, the cinematography, the editing—all of that’s for a flat frame. That frame is now gone. So, while I still think the sense of ethics and the [documentary] methods are still valid, the actual techniques of storytelling are very different. We’re now thinking a lot more about space and proximity to the viewer.”

Dennis conceptualizes that space in concentric rings of near field, medium field and far field. “Far field is important to establish the sense of place,” he explains. “Medium field adds depth and cues that this is a real environment. But the near-field presence, which is the hardest to capture, is what evokes this powerful sense at a deep level of your brain that this is real.”

He explains that though the near-field environment has the most payoff in terms of presence, it is also the most difficult to execute technically, mostly due to seams and shadows. But like any documentary medium, Dennis believes that viewers are willing to forgive some imperfect shots if the content is powerful.

For example, In the Presence of Animals, one of Condition One’s experimental short pieces, contains a key moment where a bison walks directly up to the camera and the viewer can see its eye and experience the immensity of the animal. “It’s one of the most broken shots we’ve ever put out,” Dennis admits. “The exposure changes, the seam changes, it disappears for a second. But in the end it didn’t really matter because people, when they came out, just said, ‘I was next to this massive bison.’ They weren’t saying, ‘Oh, I saw the seams, or I saw this, or I saw a tripod.’ There’s no way to remove a shadow from a moving animal. And so you see the tripod shadow fall on the animal. These are all things that would be nice if we could completely remove them, but if the presence is there, you can get away with a lot of those errors. But that said, we were really aiming for the highest-quality stitching and seamless images without any of those small image-quality errors.”

Gabo Arora, senior advisor and filmmaker at the United Nations, and, through Vrse.works, director and producer, with Chris Milk, of the UN-commissioned ‘Clouds Over Syria’ and ‘Waves of Grace’.

Gabo Arora, a senior advisor and filmmaker at the United Nations, is also one of the “creators” withVrse.works, a virtual reality studio. He directed, with Vrse.works creative director Chris Milk, the UN-commissioned Clouds Over Sidra and Waves of Grace, two powerful pieces that take on the refugee and Ebola crisis, respectively. Arora has spent over 15 years doing humanitarian work in disaster and conflict zones and thinks VR is an ideal medium for social impact work because it “levels the distance between the subject and viewer, giving a more equal exchange. With less distance is more understanding and more engagement.

“VR is also less dominated by information sharing,” he continues. “It is more about making you feel. The concern is not as much about, ‘Did you understand?’ but [more about], ‘Do you feel present?’ A storyteller in VR has to communicate much more subtly, which allows for more reflection, more poetry, as there is more experimentation.”

Both of Arora’s acclaimed virtual reality pieces take on issues that received extensive mainstream media coverage, but he believes VR can take viewers beyond the “one-dimensional and often sensational” approach of traditional media. “Reality is often much more nuanced and complex, and often times ordinary,” he says. “I really felt VR could capture what was missing. Somehow if you could really be there and share in the experience with the people, at their level, I thought it would be compelling and new.”

The newness and compelling nature of VR, however, may be a double-edged sword. “I do worry that filmmakers—and journalists in particular—may make the mistake of believing that VR is enough, that somehow the technology will amplify their cause because the technology is so compelling,” Arora explains. “That just won’t last, but [it] is an easy trap to fall into. You have to see it as something that is harder, not easier, than traditional ways of doing things.”

From Gabo Arora and Chris Milk’s ‘Waves of Grace’, commissioned for Vrse.works by the United Nations. Courtesy of Sundance Film Festival.

“Story is [still] king,” Arora maintains. “But how you tell it has to be completely different because you cannot rely on the same tropes as before. You can’t rely on jump cuts and close-ups; you really need to let things breathe a bit more. The pacing is also very hard, and what you think would work, when you put on a headset, doesn’t always work. It either feels too rushed or slow. The rhythm of it is still something that is hard to figure out.”

Filmmaker Lucy Walker, who made ‘A History of Cuban Dance’ through Vrse.works.

“One of the most exciting aspects of VR is that the visual vocabulary hasn’t been settled upon—it’s still being invented,” notes Academy Award-nominated filmmaker Lucy Walker, another creator in the Vrse.works collective. She is particularly interested in camera placement, choreography and how height and distance from the subject affects the experience, and says that she loves placing the camera so that “there are multiple points of interest within the 360-degree field of view.”

For her piece A History of Cuban Dance—a story she chose because Cuba is a place that people are eager to visit and “VR is the closest thing we have to a teleportation machine”—Walker and her team “experimented with the degree to which we inserted ourselves into the midst of the action. In some shots the camera is a bit removed and takes in the dancers from roughly the position that a dance audience would conventionally observe the performance. In others, we play with the idea of entering the space of the dance.”

Part of the appeal of the medium for Walker is that “it’s possible to shoot in a very low-key way that is perfect for documentary filmmakers. One of the wonders of VR is that, as cutting-edge as it is, we’re able to shoot with a small crew. The crew size varied from just myself alone, for one shot only, to myself and a DP, for much of it, to occasionally having a sound recordist and more help as well.”

Though Walker has recently started using cable cams, advanced rigging and even “primitive” monitoring, she says A History of Cuban Dance was made using a grip kit that consisted of little more than “a c-stand and some gaffer tape.”

That is changing quickly, however. “None of the shoots I’ve done resemble one another,” Walker notes. “A month doesn’t go by without new iterations of the camera gear or stitching software. I’ve filmed with a different rig every month since September when I filmed A History of Cuban Dance.”

From Lucy Walker’s ‘A History of Cuban Dance’. Photo: Lucy Walker, Juan Carlos Zaldivar. Courtesy of Sundance Film Festival.

So what does the rapidly evolving production process for live action virtual reality look like? At the most basic level, pairs of stereoscopic cameras capture footage in 360 degrees. There are commercial options for rigs beginning to emerge, and Condition One and Vrse.works both work with bespoke rigs that have been in development for years.

Part of the pre-production process is figuring out where the crew is going to hide, or alternatively, how the crew is going to be a part of the shot. Though filmmakers can shoot with plates and capture 180 degrees at a time (especially since each shot will be worked on in post-production anyway), most seem to think that shooting 360 degrees is preferable for the fast-paced, dynamic work that occurs during documentary production. It is also perhaps the more ethical choice.

The footage from all of the cameras is then imported into editing software and stitched together, beginning with a rough stitch. Once the final sequence is chosen, the fine stitching is a lengthy, tedious process.

“The seams are one of the first technical challenges,” Dennis explains. “These seams will break that sense of presence, and eliminating them can be a very time-consuming process in post-production. An artist goes in and rotoscopes, compositing and trying to match every pixel with the next frame. And with 16 cameras, that can take weeks, if not months, for a single shot. So developing the software to do that became the next critical component of the pipeline to assemble these videos together in a seamless, stereoscopic 360-degree video.

“Then playing the stereoscopic videos back is very demanding,” Dennis continues. “Computationally demanding. These are 4K videos. Once they’ve been stitched, they’re at 48 frames per second. And that we know is the bare minimum for VR. Traditional film is shot at 24 for that kind of filmic look. We’ve kind of gotten used to that. But in VR, if you shoot at 24 frames per second, it looks stuttery. It looks like you’re looking at video. So we then think, 60 frames, 90 frames, and eventually 120 and up will be required to really get the smooth, natural feeling of movement in VR.”

Sound is another critical component, Dennis points out. “We’re designing the capture and the post-production workflow to achieve realistic spatial audio. We use four microphones, mini- shotguns, offset by 90-degrees. And then we run them through software that mimics that human ear and the shape of the head to create these binaural audio tracks. And then we use a custom audio player to fix those four different audio tracks in space.”

Dennis says that using this audio production process makes it “so as you look around, the audio stays where it should be. It’s very subtle but extremely powerful in convincing the mind that this is a real experience.” Eventually, he thinks, the camera system and software technology will evolve far enough that one person could be shooting virtual reality in the field.

Animation is another production option for documentary filmmakers looking to explore the medium. All of VR pioneer Nonny de la Pena’s “immersive journalism” pieces use 3D animation, constructed using journalistic standards. For example, her piece Use of Force(about a border police brutality case) uses primary sources such as audio recordings from actual 911 calls and floor plans of the house where the incident took place to reconstruct the event as accurately as possible.

From James Spinney and Peter Middleton’s ‘Notes on Blindness’, for which Arnaud Colinart produced the VR component. Courtesy of Sundance Film Festival.

Arnaud Colinart, a producer at AGAT Films/ExNihilo and one of the creative directors of the virtual reality component of the project Notes on Blindness, thinks that “animation and CGI gives the best performance in VR for now.” Notes on Blindness is based on the audio recordings of British professor of philosophy and theology John Hull, who documented his experience of going blind. The story was first conceived as a short film for New York Times Op-Docs in 2014, and directors James Spinney and Peter Middleton premiered a feature-length version of the film in this year’s New Frontiers competition at Sundance. With Amaury La Burthe from the French start-up Audiogaming, Colinart led the effort to create the accompanying virtual reality experience, called Notes on Blindness—Into Darkness.

“I think right now, virtual reality is at the same point as the birth of cinema, with the Lumière brothers and Train Pulling into Station,” Colinart asserts. “But just after that, you had Georges Méliès, who created A Trip to the Moon, which is sometimes considered the first narrative film because he used visual effects to create story. Now we see the birth of VR storytelling as more than just gadget or gimmick.”

The VR experience relies on Hull’s original audio recordings to guide the experience. Each chapter uses abstract 3D animation to explore the experience of going blind through a different memory. Making a virtual reality experience about blindness is perhaps a counterintuitive choice, but the emotional resonance of the experience suggests that virtual reality shows great potential for multi-sensory immersion.

From ‘Notes on Blindness—Into Darkness’ (Dirs.: Arnaud Colinart, Amaury Laburthe), the VR component of James Spinney and Peter Middleton’s ‘Notes on Blindness.’ (C) Ex Nihilo, Archer’s Mark, ARTE France – 2016. Courtesy of Sundance Film Festival.

The filmmakers developed the experience using Unity, a multi-platform gaming development tool, and utilized the Agile method—an iterative, prototype-driven design process popular in software development. Colinart thinks there is a lot to borrow from software and video game-development, and that creating VR experiences in this manner will help accelerate the learning process for VR storytelling and its mise en scènevocabulary. “I think all stories can be told in VR, but we need to find the good way to do it,” Colinart maintains. “It’s like, you read books, and you say, ‘How can I adapt this in a movie?’ I think all books can be adapted, but you have to find the right way to adapt it to another way of telling the story; and I think it’s the same for VR. This is the start of this art of writing, as we discover little by little what VR can bring to storytelling.”

The Notes on Blindness experience uses chapters, a format in which Colinart sees great potential for VR because it mitigates some of the headset discomfort issues that may limit longer-form pieces. “Maybe we will have long-form stories, but they’ll be broken up into chapters and consumed that way,” he suggests.

From ‘Notes on Blindness—Into Darkness’ (Dirs.: Arnaud Colinart, Amaury Laburthe), the VR component of James Spinney and Peter Middleton’s ‘Notes on Blindness.’ (C) Ex Nihilo, Archer’s Mark, ARTE France – 2016. Courtesy of Sundance Film Festival.

Beyond the headset ergonomics, creating experiences that don’t induce motion sickness is another component of production that is new for most documentary filmmakers. While some VR reviewers have bemoaned the stationary camera in many pieces, Dennis argues that “the fastest way to make someone motion sick is to move the camera in an unstabilized way.” He thinks this will change as the medium advances and viewers develop “VR legs,” but for now he suggests that filmmakers start with a locked tripod.

Another issue Dennis sees is the presentation of virtual reality experiences. In film, he says, there is a strong viewing tradition. “Lights down. Someone introduces the director, they say few words, and they say, ‘Quiet, cell phones off,’ and then you watch the work.” In virtual reality, he says, “It’s put on this headset, and you jump in, then you jump out.”

The viewing presentation, Dennis notes, is particularly important for experiences like Condition One’s Factory Farm, which takes viewers into a factory farm and active slaughterhouse facility in Mexico. In it, viewers are guided by José Valle, the director of investigations at the advocacy organization Animal Equality. “Every time you move into a new environment, you ask, ‘Why am I here?'” Dennis says. “And with José, he’s doing his normal work. He is documenting abuse for his investigations. And so you get to be with him while he’s working, while he’s filming, gaining evidence. It is really helpful to have a guide, especially in this type of situation, which is so graphic and gut-wrenching. He gives you the courage to stay and watch it.”

Within the experience, Valle also gives warnings about the material ahead, telling viewers that they’re going to see very graphic footage, and warning them, “This is your last chance to leave.” It builds a level of trust in the guide, as the viewer has ample opportunity to remove the headset before entering the slaughterhouse.

Trust, Dennis says, is essential to this type of work. “He’s there with you. And he’s experiencing it. So in a way, you feel like you’ve got someone with you, and you’re not alone. You don’t want to run away.”

At Condition One’s Sundance exhibition, Valle was actually there to greet viewers in person as they came out of the VR experience. Dennis recounts how one viewer got through the entire experience and how she held it together until she saw him in person. “Then it just struck home: ‘That was real! He’s right here!'” The viewer burst into tears and shook Valle’s hand. “People were having really tremendously emotional responses and having a moral inquiry into their own actions, which I think is the power of VR.”

Casey Freeman Howe is a graduate fellow at the Center for Media & Social Impact at the American University School of Communication in Washington, D.C.