While it was easy to find lawyers drumming up business by trash-talking fair use at SXSW, it was hard to find a documentary that hadn’t employed it, sometimes lavishly. Furthermore, you could even see fair use at work in fiction film work.

“Fair use is so important for independent producers like myself,” said Sandy McLeod, maker of “Seeds of Time,”about the crucial importance of agricultural seed banks for successful climate-change adaptation.

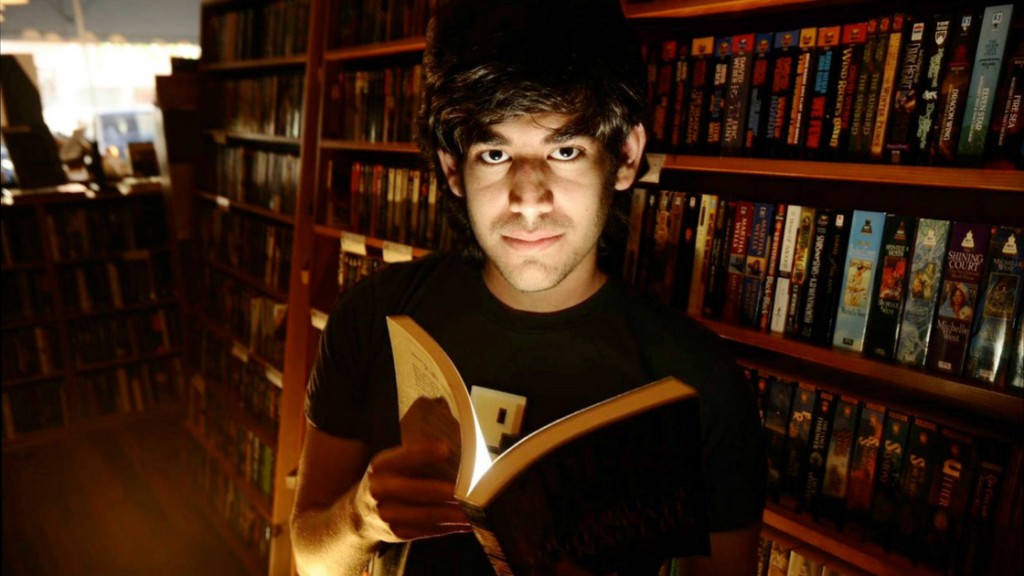

Films that told recent history employed fair use to tell that history. Margaret Brown’s “The Great Invisible,” which told the story of the human and social consequences of the BP oil spill, used fair use, and has already obtained errors and omissions insurance for it. Katy Chevigny, co-director of E-Team, said, “Sure, we used lots of fair use.” Brian Knappenberger noted, “There was a lot of fair use in “The Internet’s Own Boy,” as in all my films.” (Knappenberger, of course, is acutely aware of copyright affordances, since he has chronicled the cutting edge of controversy in digital practices; his previous SXSW film was “We Are Legion,” an extraordinarily sophisticated retelling of the evolution of Anonymous.)

The filmmakers of “Print the Legend,” about the race to bring a prosumer 3D printer to market, also employed fair use. Co-director Clay Tweel noted, “We have fairly used a fair amount of [the third-party footage], because of the context. We wanted to paint a picture of as many years of these characters as we could. We are big supporters of fair use in documentaries in order to make the richest viewing experience possible.”

That’s entertainment.

Two films heavily drew on entertainment films to tell their own story. For “That Guy Dick Miller,” about a leading character actor in movies (Joe Dante, Martin Scorsese, and Roger Corman all used him), Elijah Drenner drew on what he learned making “American Grindhouse” about so-called exploitation films (think “Freaks“). For this film, he was able, he said, confidently to employ fair use; about half the third-party material in “That Guy Dick Miller” was fairly used.“Beyond Clueless,” which revels in the clichés and tropes of teen movies, also employed fair use, as did other films that concerned popular culture, such as “Rubber Soul.”

Fiction films are increasingly employing fair use as well, as was demonstrated at SXSW by “Kumiko, the Treasure Hunter,” about a lost-soul Japanese woman who decides to find the loot buried in the (yes, fictional) film “Fargo.”

“‘Kumiko’ is an example of a trend,” said Los Angeles-based Michael Donaldson, whose firm has a fair use specialty. “We are getting more and more requests for fair use within fictional films. In the indie film community, you’re working on a doc one day and you’re working next day on a fictional film with a friend. So fair use has entered the conversation within the indie film community.”

Content bullies.

Fair use also emerged in a panel on content bullying and what to do about it. Sometimes even people who know fair use well, like remixer extraordinaire Jonathan McIntosh, face “content bullies,” by which he and lawyers at New Media Rights mean this: Digital Millennium Copyright Act terms make it way too easy for content holders to pre-emptively cry infringement without checking whether their work has been fairly (and therefore legally) used. If you want your work restored to YouTube or elsewhere, you need to know your rights. You can find out more about what they are at the Center for Media & Social Impact’s fair use pages, and New Media Rights accepts legal clients.